In a constant quest to run faster and further, we should not as runners be surprised when from time to time things start hurting. Performance gains come from forced adaption, i.e. your body will only adapt if you force it to work through sufficient load.

Just as doing arm curl with a pencil will not make your biceps any bigger, keeping all your sessions at the same intensity will not help you run any faster or further. However, you can of course do too much (as anyone who has suddenly tried curling a 30kg dumbbell will confirm) and research confirms that the key factor in 60-70% of running related injury is inappropriate training load.

When faced with running related injury/pain, it is important to bear this percentage in mind. The basic law of supply & demand means that runners are bombarded with an ever increasing list of ‘fixes’ to choose from, each being expertly marketed to not just runners but also therapists eager to learn the latest ‘technique.’

As a result, the most likely source of a runner’s injury/pain often gets lost within a sea of reasoning that may well sound very impressive but in reality lacks any form of evidence based rationale. Needless to say, if incorrect assumptions are made regarding the source of an injury/pain, it is very likely that the treatment prescribed will be flawed.

This article aims to provide runners (and therapists) with a basic checklist to work through in order to make sure that the most likely cause of injury/pain is not missed, meaning you will hopefully get back on track sooner rather than later.

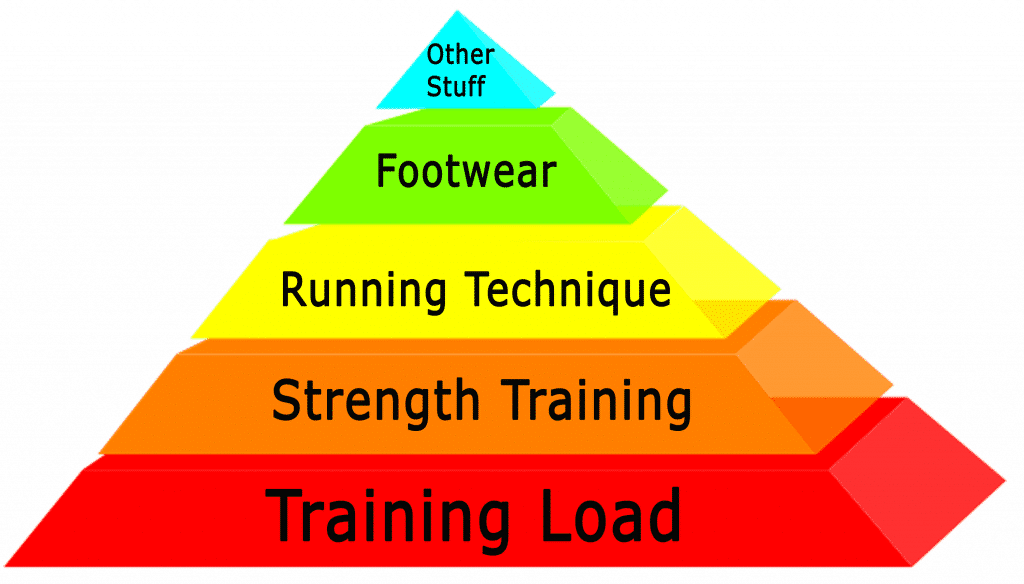

Evidence Pyramid

In the diagram below, I have presented potential causes of running related injury in order of evidence. In other words, the bottom part of the pyramid represents factors & interventions that are most supported by evidence, whilst the top of the pyramid represents those with the least evidence. Let’s take a look at them one by one.

Training Load

As stated in the introduction, research shows that the key factor in 60-70% of running related injury is inappropriate training load (Hreljac et al. 2004: Impact & Overuse Injuries in Runners). By inappropriate load we are talking about a sudden increase in either running frequency (runs per week or day), intensity (speed, incline, etc.) or distance (time on feet).

Though your body is a master at adapting to new demand, tissue & system thresholds are put in place to protect you from doing yourself serious harm. If you suddenly exceed these thresholds you are very likely to experience pain and/or injury.

Keeping a training diary of what you do not just each week but also over months or even years can be an excellent way of monitoring load and avoiding sudden jumps.

You will notice throughout this article that I make a point of separating ‘pain’ and ‘injury’. The distinction is important as they are not the same thing.

Pain is a warning message from the brain that based on the sensory information it constantly receives it looks like danger is imminent. It’s a defence mechanism, an alarm; actual tissue damage may not have occurred yet as it would be pretty useless warning system if the alarm only went off after damage had occurred.

[bctt tweet=”Pain is a warning message from the brain @Runners_Connect” via=”no”]

Pain and actual tissue damage can obviously occur at the same time but it’s not a prerequisite, and how much pain you feel is not an accurate measurement of how much tissue damage has been (if any).

It’s important to remember this when assessing why your body is hurting. Research shows that fearing or worrying about serious structural injury can increase pain (e.g. seeing graphic images or disturbing metaphors like ‘wear & tear’ or ‘degeneration’), just as understanding pain and realising that things can hurt a lot even if there is not serious tissue damage (e.g. a paper cut) can reduce pain.

This is not to say that pain is all in your head or imaginary – all pain is very real. It just means that when trying to recover from pain we need to remember that there is always a brain involved, not just an uncomfortable body part. Focussing solely on ‘fixing’ the body part risks missing out an important part of the recovery strategy.

For more information, please read An Introduction To Understanding Pain).

Strength Training

If inappropriate training load is a key factor in running related injury, it makes sense that getting stronger so you can handle more load will be a good way of reducing risk of injury. And the research supports this: studies show that strength training can reduce sports injuries to less than 1/3 and overuse injuries by almost 50% (Lauersen et al. 2013: The Effectiveness of Exercise to Prevent Sports Injuries).

As I have mentioned many times in other articles, runners often get way too obsessed by stretching, often because therapists still too often erroneously prescribe stretching as a cure for injury/pain. Running does not require much more flexibility that walking.

How is a stretch that puts you in a position you will never use whilst running going to help you? You are not a dancer, you are not a martial artist, you are a runner. The 2013 Laursen study mentioned above found no correlation between stretching and injury prevention. Other than feeling good, stretching probably does very little to help you reduce injury, run faster or further. In fact, too much flexibility can actually reduce performance and increase risk of injury.

[bctt tweet=”Too much flexibility can actually increase risk of injury @Runners_Connect” via=”no”]

When assessing the cause of injury/pain, checking strength is essential. Running is essentially a series of hops from one leg to the other, and the ability of the muscles/tendons to provide propulsion is dependent on them having sufficient ‘spring’. Every time we land during running, our muscles/tendons store ‘elastic energy’ from the ground and then use it for propulsion.

This concept of a lengthening of the muscle-tendon unit followed by a shortening is referred to as the Stretch-Shortening Cycle (SSC) and requires us to have ‘stiff’ springs, i.e. more like a Pogo Stick rather than a Slinky. Trying to increase training load without having sufficient strength will most likely lead to injury/pain.

For more information, please read Why Improving Calf Strength and Checking Mobility Can Improve Performance)

Running Technique

We’ve checked training habits, we’ve checked strength, what’s next? Well, how you run will obviously affect what parts of your body are put under stress. If we define pain/injury as sign that the load threshold of a certain tissue has been exceeded, checking your running form can be a very useful way of either seeking the source of the issue or maybe finding an alternative way of running whilst you recover.

We have already mentioned that pain is not just a product of tissue damage. How much pain you feel and indeed whether you feel it at all is based on many types of sensory feedback. Tweaking your running form so that you can experience pain free running can be a great way of helping the nervous system recover.

Unfortunately, many gait analyses spend too long looking for biomechanical flaws or trying to deduce what shoes would be best for you. Both of these areas are very grey when it comes to research, and a lot of the respective information presented to runners during gait analysis is unfounded (especially in footwear prescription).

For more information, pleaser read 3 Reasons a Gait Analysis at a Running Store May Not Help You Find the Right Shoe and listen to our podcast The Importance Of A Full Body Gait Analysis).

Footwear

We are getting towards the top of the pyramid, which means evidence is getting scarce. Regular readers will be aware that basing shoe selection on how much you ‘pronate’ (a perfectly natural and vital part of foot mechanics) is not backed by any science.

Though some runners wearing an ‘anti-pronation’ shoe may see pain disappear, others do not, and some see symptoms get worse. Research has clearly shown that categorising runners into three groups based on their foot arch (high/normal/low) ignores natural human variance.

Now that said, we do know that different shoes (and insoles) will load tissues differently; it’s just a question of working out what works for your body. Modifying footwear can be a useful way of resting sensitised tissues and allowing recovery but as far as choosing which shoe is best for you, gait analysis will rarely provide the answers.

Other Stuff

We have reached the top of the pyramid. Despite this being the smallest part in terms of evidence, it is sadly a place where many runners (and therapists) spend way too much time. This may well help explain why the incidence of running related injury is not on the decrease.

[bctt tweet=”The ultimate injury guide everyone needs to read @Runners_Connect” via=”no”]

Anything we haven’t mentioned yet sits here: stretching, foam rolling, kinesiology tape, acupuncture, etc. I am not saying these are all a waste of time but as far as running related injury goes they are the least supported by evidence.

There will always be runners who swear by them of course but anecdotal evidence doesn’t really count for much. Just because you do one of these for six weeks and then see your pain disappear does not mean that what you did was the solution. How do you know it wasn’t the natural healing process of the body that caused the pain to go, or the fact you haven’t been running for six weeks?

Devoting too much time at the top of the pyramid risks missing out on evidence based causes & solutions at the bottom, which could result in you staying injured and/or in pain for an unnecessary long time.

In Summary

Treatment of running related injury is not black & white. Research has yet to provide us with answers as to why some runners get injured and others do not. This can be hugely frustrating for the runner who just wants to get back out there, as advice can vary considerably depending what you read or who you speak to.

For this reason, is it vital to check for the most likely causes of running related injury/pain first of all, to use what quality research tells us before spending time & money on less evidence based investigation.

For the majority of runners, the solution to pain/injury will involve making appropriate adjustments to training, strength and running form (in that order).

This may not sound as attractive as modifying your biomechanics, buying the perfect pair of shoes or lying back on a couch whilst someone ‘fixes you’ but until the evidence tells us otherwise this is the best approach to follow.