Of all the areas of the body susceptible to running related pain or injury, most runners will agree that the calves rank high.

Logic would suggest that this is because the calves have to work particularly hard during running. Which is indeed the case as the calves handle up to eight times our body weight with each step.

And yet, ask a group of runners what they incorporate into their weekly training to help prepare their calves for such demands and answers will vary considerably.

Stretch them? Strengthen them? Just run?

So, let’s take a look at what most of us should be doing to reduce the incidence of calf injuries.

Anatomy of the calf

The calf muscle complex is made up of two muscles, the gastrocnemius and the soleus.

Most runners are already aware of the gastrocnemius because it sits on top of the soleus and is far more visible.

Standing on tip toe is generally enough for us to be able to see the left and right head of the gastrocnemius become prominent. These two heads continue upwards to cross the back of the knee and attach to either side of the thigh bone (femur).

The soleus muscle, like the gastrocnemius, has its lower (distal) end attached to the heel bone via the Achilles tendon. However, its other end (proximal) does not cross the knee. Instead, it attaches under the knee to the tibia and fibula.

This anatomical difference means that despite being less visible, the soleus actually contributes more to force production during running than the gastrocnemius because during running the calf has to deal with loads whilst the knee is bent.

Whilst the gastrocnemius produces forces of about three times body weight during running, research shows that the soleus produces around eight times body weight.

Preparing The Soleus For Load

Regular readers will be aware that as far as distance running goes, I tend to regard ‘stretching’ as way overrated (Do Runners Really Need To Be Flexible).

The calves provide a particularly good example of why.

In a 2014 study looking into what recreational runners believe are risk factors for running injuries, ‘not stretching enough’ sat at the top (along with ‘wearing the wrong shoes’ and ‘not warming up’). Much of this belief is fueled by the fact that many therapists still routinely give out stretching exercises as part of a ‘solution’ for calf pain.

In reality, there is no evidence that stretching is beneficial for injury prevention, performance enhancement or reducing post run soreness.

One of the main reasons runners stretch so much is because they believe aching muscles are ‘tight’ but in fact what most of us are actually saying when we complain of ‘tightness’ is that our muscles feel sore.

This is a very important distinction because if we believe our aching muscles are ‘tight’ then all we will do to rectify the situation is stretch them.

But what if they are not tight?

What if our soleus muscles are aching because they are not able to deal with eight times our body weight every step? Will stretching help them handle these loads better in the future?

No – but you know what will? Strengthening them.

Checking For Tight Soleus

It’s only fair that I mention at this point that some research does suggest that a certain level of inflexibility in the soleus may for some runners increase risk of injury.

I say may because it is very difficult to say what’s ‘normal’ in terms of calf flexibility.

Natural variance in human anatomy means that there is rarely an ‘optimum’ amount. What works for one runner may be entirely different from what works for another.

That said, if you do suffer from frequent calf issues, you may well find your therapist performing the following ‘knee-to-wall’ test as part of a thorough assessment.

The main movement that calf flexibility permits is ankle dorsiflexion. By this, we are referring to how far your shinbone can pass over the weight bearing foot.

If you are struggling to picture this moment during running, imagine yourself squatting: in order to get down to the floor, your shins need to be able to move forwards (which is why you can’t squat in a pair of ski boots).

If sufficient ankle dorsiflexion is not available, your body will have to find another way of getting the movement done; this typically involves another joint and or tissues doing more than their normal share of work, which depending on your system’s thresholds may eventually lead to overloading and pain/injury.

One potential reason for reduced ankle dorsiflexion is restrictive soleus muscle.

Measuring Ankle Dorsiflexion

The following ‘knee-to-wall’ test is a good way of measuring ankle dorsiflexion. There is also a standing test to examine gastrocnemius flexibility but given the important role of the soleus in running we will just focus on just that for now.

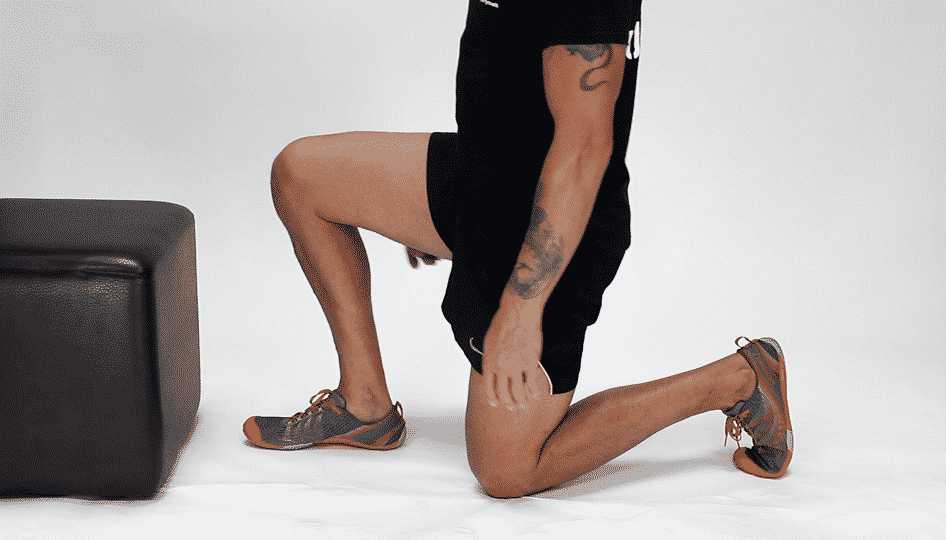

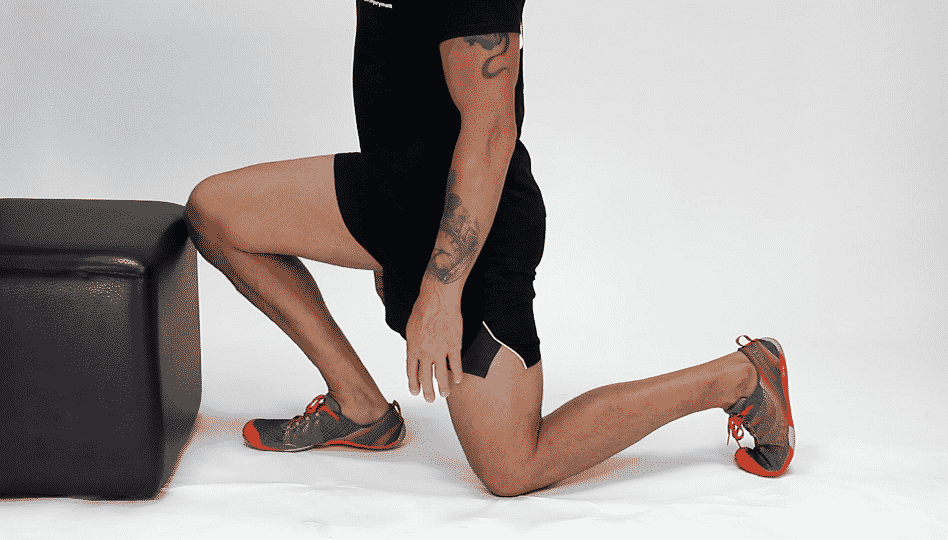

Facing a wall or box as seen in the photo, take yourself down into a kneeling lunge position so that your front foot is about 10cm away from the wall.

Facing a wall or box as seen in the photo, take yourself down into a kneeling lunge position so that your front foot is about 10cm away from the wall.

Lunge forwards to see if you are able to get your front knee to touch the wall without lifting the front heel off the ground.

If your front knee can touch the wall at this 10cm distance without lifting the front heel, move back a bit further away from the wall and repeat the test until you discover your maximum distance before the heel has to lift.

If your front knee can’t touch the wall, try starting a little closer and likewise record the new distance.

Make sure during the test that your front knee travels directly forwards over the centre toe; if you allow it to drift inwards, the inner arch of the front foot will fall and you will be able to get much further from the wall (giving a false result).

Placing a block to record the distance is a useful way of then swapping legs and comparing range in the opposite ankle.

In healthy subjects, research produces maximum distances of 5-20 cm, with an average of 10cm. In terms of the angle created between your front shin bone and an imaginary vertical line perpendicular to the ground, this is equivalent to 35-380.

Some research suggests that a distance under 10cm or angle under than 350 correlates with increased risk of injury, but as I mentioned above the results of this test do need to form part of a thorough assessment, and remember not everyone fits the norms.

What happens if you are MORE flexible than normal?

Let’s imagine you achieve a 20cm distance from the wall. Is this proud feat of flexibility a sign that you are bullet-proof?

Sadly, no.

As far as running goes, being ultra flexible is not particularly useful as the range of movement required to run is not much more than that of walking.

In fact, having high levels of flexibility in the calf muscles may well hinder your running and could well increase risk of injury.

Running is essentially a series of hops from one leg to the other, and the ability of the muscles/tendons to provide propulsion is dependent on them having sufficient ‘spring’.

Every time we land during running, our muscles/tendons store ‘elastic energy’ from the ground and then use it for propulsion (Check out more on Proper Running Form).

This concept of a lengthening of the muscle-tendon unit followed by a shortening is referred to as the Stretch-Shortening Cycle (SSC) and requires us to have ‘stiff’ springs, i.e. more like a Pogo Stick rather than a Slinky.

Research shows that amongst elite runners, the leaders have less flexibility, not more.

Despite what we read and hear every day, a certain amount of stiffness in the muscles and tendons is actually a good thing, and guess what develops this stiffness and puts the spring back into our step?

Strength training.

How To Strengthen The Soleus Muscle

We have come full circle and arrived back at the importance of strength training for runners (learn more on measuring strength and flexibility).

So how do we target that all important soleus muscle?

We recall from earlier on that the reason the soleus contributes more to force production during running than the gastrocnemius is because during running the calf has to deal with loads whilst the knee is bent.

Research shows that in order to target the soleus muscle during a calf raise, the knee needs to be bent to at least 800.

Trying to maintain this amount of bend in the knee whilst standing can be very uncomfortable for the knee. So the best the most practical way of hitting the soleus is performing the calf raises whilst seated.

How Much Weight Should I Use?

The soleus is an inherently strong muscle, so to achieve exhaustion by 12 repetitions you will find you need to use a lot of weight.

Most healthy runners will need half their body weight to reach failure by 12 repetitions.

So that 10kg kettlebell in your bedroom is unlikely to be enough.

For this reason, when it comes to soleus strengthening (and Achilles rehabilitation), most runners will need to use the weight facilities at a gym, although I do have some runners at home using sacks of potatoes, sand or even small children to achieve the necessary levels of fatigue.

Work The Eccentric Phase

One important note when it comes to soleus strengthening is remember to strengthen not just the lifting part of the exercise but also the lowering part.

The soleus works hardest when the foot has landed and body weight is passing over it; the muscle is in effect controlling loads whilst it lengthens, something referred to as eccentric strength.

To prepare for these demands we need to make sure we lower the heels slowly during calf raises, maybe even use two feet to raise the weight and just one foot to lower.

Muscles are typically stronger in the eccentric part of an exercise, so using two feet to get the weight up and then just one to lower will help you fatigue the soleus eccentrically.

Achilles Tendinopathy

We have mentioned that both lower ends of the calf attach to the heel bone via the Achilles tendon (If you have an achilles injury, check out The Ultimate Runner’s Guide To Achilles Tendon Injuries).

For many runners, repeated calf overload can soon develop into Achilles tendon issues.

Unless you have suffered a sudden twist, impact or fall, most cases of Achilles tendinopathy (irritation of the tendon) are caused by chronic overloading, i.e. doing too much for too long.

In contrast to the inflammation typically associated with recent, acute injury, persistent Achilles pain is often a sign that the tendon has suffered a certain degree of degeneration.

Although this sounds scary, one of the many great things about the human body is that given the right stimulus it can rebuild itself.

Research shows that the pathway to stimulating tendon repair and restoring normal sensitivity thresholds in cases of Achilles tendinopathy is… you guessed it, seated calf raises.

In Summary

Whether for performance gains or as part of rehab for a painful Achilles, strengthening of the soleus muscle can be a highly beneficial addition to any runner’s strength training program.

Remember to play around with different tempos and suitable progressions to work the isometric, eccentric and concentric components, and use enough weight to stimulate the desired strength gains.

As is always the case when embarking on any new exercise (especially if you are in pain), seek the advice of a recommended running injury specialist if you have any doubts as to the suitability of the exercise.