You’re cruising along in a workout, feeling great, when all of a sudden—pop!—you feel a gristly pop in your calf and you’re reduced to a hobble.

Or maybe it doesn’t come on all at once; you wake up one day and head out for your morning run and feel a slight tightness in your calf. Instead of loosening up as you continue, it just gets worse.

In either case, you’ve got a calf strain: chronic or acute damage to the muscle fibers that make up the calf muscles.

What is a calf strain?

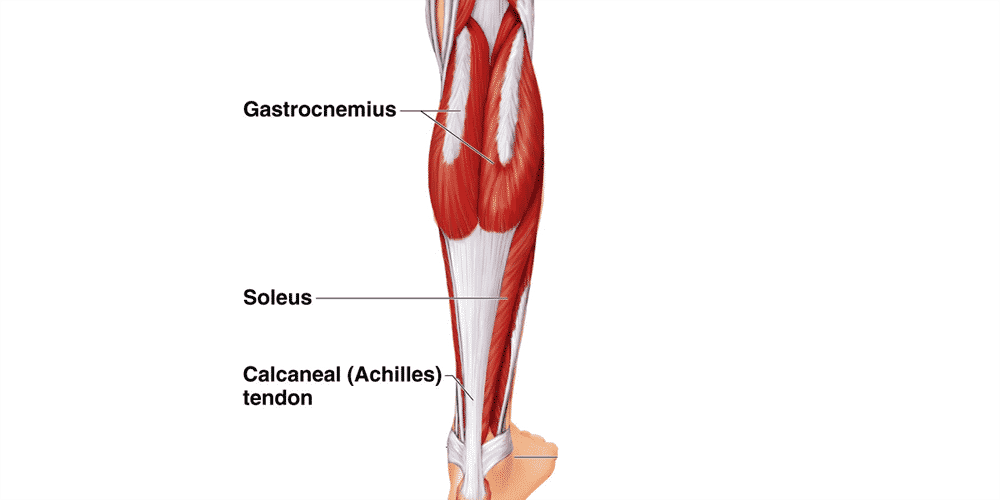

In medical circles, the calf muscles are referred to collectively as the triceps surae, because there are three of them.

Two of the three are the medial and lateral heads of the gastrocnemius, which is the muscle that most people think of when they hear the term “calf strain.”

But the triceps surae also include the soleus, which is a shorter, more slender muscle that connects to the Achilles tendon and runs lower and deeper than the two head of the gastrocnemius.

A calf strain can consist of an injury to any one of these three muscle units.

Gastrocnemius strains are fairly easy to identify.

You’ll feel pain, soreness, and tightness deep within the muscles along the back of your lower leg. Doing a classic “calf stretch” will often provoke pain, as will doing calf raises or vertical hops.

Depending on the severity of the strain, you may or may not have pain while walking.

Soleus strains are a little more difficult to diagnose, because they can sometimes masquerade as Achilles tendon problems if they occur low enough along the muscle.

Like a gastrocnemius strain, you’ll have soreness, tightness, and pain in the soleus muscle. Soleus strains can be distinguished from a gastrocnemius strain by comparing the pain elicited from a traditional straight-legged calf stretch to the pain from a bent-knee calf stretch.

Since the gastrocnemius muscles cross the knee joint, but the soleus does not, a “gastroc” strain will not be as painful with the knee bent, while a soleus strain will often be more painful.

With any type of calf strain, you might be able to feel an area of muscle tissue that is especially tight or tender, either by palpitating with your fingers or rolling on a stiff foam roller or PVC pipe.

According to J. Bryan Dixon at the Marquette Sports Medicine Institute, the gastrocnemius is more prone to injury for two reasons.

First, it crosses two joints (the ankle and the knee), and second, it has a higher proportion of fast-twitch type muscle fibers.

Both of these mean there’s an increased mechanical load on the muscle, predisposing it to injury. In contrast, the soleus only crosses one joint, and has more slow twitch muscle fibers.

Dixon also notes that 17% of calf injuries involve strains to both the gastrocnemius and soleus. If you’re having trouble isolating your calf injury to one specific muscle, this might be why.

While it’s fairly easy to diagnose a calf strain without any advanced medical testing, an MRI is sometimes warranted if a doctor wants more information on the exact location or severity of the injury. This is usually used in severe strains and frank tears to the muscle.

Risk factors for calf strains in runners

A 2001 study on muscle strains in Australian football players identified some useful predictors of calf strains in athletes.

First among these was a history of previous injury to the same location. Some people seem to be prone to calf strains, and a recent or historical calf strain is by far the best predictor of this.

There are likely biomechanical roots to recurrent calf strains—whether for gait-related or anatomical reasons, some people rely more on their calf muscles to generate power, or have a muscular structure that is less able to handle high loads.

Another risk factor for calf strains was age. Older footballers had a higher incidence of calf strains (but not strains to some other muscles). This mirrors anecdotal data from runners—master’s runners seem to suffer calf strains much more frequently than their younger competitors.

One study by researchers in Sydney, Australia suggests a connection between lower back problems and calf injury.

In their paper, they demonstrate that injuries at the L5-S1 level are increasingly common as Australian football players get older, and they hypothesize that nerve compression at this spinal joint could explain why calf strains, but not some other types of muscle strains, are also more common as players get older.

While this has not been validated in independent studies, it is nevertheless an interesting avenue for explaining why calf strains occur more often in older athletes.

Mainstream treatments for calf strains

Once you have suffered a calf strain, you should treat it with two strategies: reduce stress on the calf to allow it to heal, and work to strengthen the calf muscle so that it’s more resilient in the future.

Obviously, your initial priority is to reduce stress and allow healing, while later on in the recovery process, your focus should switch to rehabilitating and increasing the resilience of the injured muscle.

When it comes to reducing stress on the calf, you probably already know what to do—stop running, cross train for a while, and if you do run, avoid high speeds, steep hills, and shoes with an aggressive heel-to-toe drop.

One less obvious way to reduce stress on your calf is to evaluate whether there are any deficiencies in your gait or muscular strength that are increasing stress on your calf muscles when you run.

Since the calves help propel you off the ground, some simple biomechanical analysis predicts that if you have a deficiency in your glute muscles (the other main muscle group that propels you off the ground), you might need to rely more on the calves for forward propulsion. (we have an entire course and gait analysis available just for this)

As such, strengthening your hip muscles should be a priority.

This is especially useful since hip strength work can be done very early in the rehab process, while your calf is still too tender to do any calf-specific strength work.

A standard hip strength routine that includes glute bridges, clamshell raises, and the “monster walk” (using a TheraBand) should do the trick.

Improving the resilience of the calf muscles is a little trickier.

You’ll want to develop a comprehensive rehab program for the calf muscles which starts with simple low-load exercises and progresses over time to heavier, more complex exercises.

RunnersConnect Insider Bonus

Download our free Calf Strain Injury Prevention Routine!

It’s a PDF with images and descriptions of the most effective prevention and rehab exercises for runners who suffer from calf strains.

Secondary treatments

Calf strains have a nasty habit of becoming chronic injuries.

Some medical professionals suspect that this is because calf strains create scar tissue or muscular adhesions, which can predispose the area to being injured again—or prevent healing in the first place.

Though there’s no solid scientific research to support this, many runners report success with therapies focused on breaking down scar tissue or adhesions.

This can be as simple as rolling on a foam roller—though given the size and toughness of the calf muscles, you might find a 3″ section of PVC pipe to be more useful.

Set a timer and roll for a full two minutes, starting at the bottom of the calf muscle and gradually kneading your way to the top, then rolling back to the bottom in one smooth motion before repeating.

Some runners find that “The Stick” or the “Tiger Tail” rolling products are helpful, too.

More aggressive therapies like Active Release Technique (ART) and Graston Technique (the research on both of those treatment methods here) are worth a shot if you continue to have calf trouble.

These manual therapies seem to help runners with chronic, recurrent soft tissue injuries, including calf strains.

For support, you might also find compression socks or a calf sleeve useful. Be sure to measure your calf and ankle circumference so you can get the correct size.

Cross Training While Injured and During Recovery

Cross training is recommended while you’re injured and as you slowly return to running.

The best form of cross training for this injury is Aqua Jogging. Studies have shown that aqua jogging can enable a well-trained runner to maintain running fitness for up to 4-6 weeks.

Aqua jogging is a form of deep water running that closely mimics the actual running movement. Your feet don’t actually touch the bottom of the pool, so it is zero impact and safe for almost any type of injury. In my experience, the only time to avoid aqua jogging is when you have a hip flexor injury, which can be aggravated by the increased resistance of the water as you bring your leg up.

Because aqua jogging closely mimics natural running form, it provides a neuromuscular workout that, in addition to aerobic benefits, helps keep the running specific muscles active. The same can’t be said for biking and swimming.

The only downside to aqua jogging is that you need a pool that is deep enough to run in without touching the bottom. If you’re lucky enough to have access to a pool of this size, aqua jogging should be your first cross training choice.

In one study, a group of ten runners trained exclusively with deep water running for four weeks and compared 5km race times pre deep water running and post deep water running.

The researchers found no statistical difference in 5k time or other markers for performance, such as submaximal oxygen consumption or lactate threshold.

In a second study, researchers measured the effects of aqua jogging over a six week period.

This time, 16 runners were separated into two groups – one who did aqua jogging workouts and the other who did over land running.

Using the same training intensities and durations, the researchers found no difference between the groups in maximal blood glucose, blood lactate, and body composition.

It get’s better:

Research has also demonstrated that aqua jogging can be used as a recovery tool to facilitate the repair of damaged muscles after hard workouts.

These findings make aqua jogging an important recovery tool in addition to being the best cross training method for injuries.

Need one more reason?

The calories burned aqua jogging are even higher than running on land, so if you want to avoid weight gain while you take time off from running, this is definitely the exercise for you!

Aqua Jogging Workouts For Runners

If you’re interested in aqua jogging to rehab your injury, then the absolute best way is to use one of my favorite programs, Fluid Running.

First, it comes with an aqua jogging belt and waterpoof bluetooth headphones so you have everything you need to aqua jog effectively.

Second, they have an app that pairs with the headphones so you can get workouts, guided instructions on how to aqua jog properly, and motivation while you’re actually pool running.

This has been an absolute game changer for me when I am injured.

I used to dread aqua jogging workouts because they were so boring and it took all my mental energy to stay consistent.

But, with workouts directly in my ear, it’s changed the whole experience and I actually look forward to the workouts. So much so that I now use aqua jogging as a cross training activity in the summer, even when I am not injured.

Fluid running is an awesome deal when you consider it comes with the belt (highly recommended for better form), the waterproof headphones (game changer for making pool workouts fun), a tether (to add variety to the workouts you can do) and the guided workout app (to make your cross training structure and a whole lot more interesting).

That’s why we’ve partnered with them to give you 2 additional running-specific workouts you can load into the app when you use the code RTTT .

Check out the product here and then on the checkout page, add the code RTTT in the coupon field and the workouts will be added to your order for free.

If you’d rather do the aqua jogging workouts on your own, here are some great ideas to get you started!

Medium Effort Workouts

The Pyramid

10 minutes easy warm up – 1:00 hard, 30 seconds easy – 1:30 hard, 30 seconds easy – 2:00 hard, 30 seconds easy – 2:30 hard, 30 seconds easy, go to 5:00 in 30 second intervals and then come back down the pyramid (4:30 hard, 30 easy, 4:00 hard, 30 easy etc). Finish with 10 minutes easy cool down.

Wave your hands in the air like you just don’t care

10 minutes easy warm up, 1 minute medium (87-92% of maximum heart rate or what feels like tempo effort), 1 minute sprint (95-100% of maximum heart rate or all out sprint), 30 seconds hands in air (keep moving your legs in the running motion, but put your hand above your head), 1 minute rest, Repeat 10-15 times. 10 minutes easy cool down.

Hard Workouts

One of the difficulties of cross training is replicating those truly lung-busting, difficult workouts.

So, if you’re going to be pool running quite a bit due to injury or limited training volume, invest in a bungee cord designed for sprinters.

Tie one end of the resistance band to a sturdy object (pole, lifeguard stand, pool ladder) and bring the other into the water with you.

Put the strap around your waist and begin aqua jog away from your starting point.

You’ll begin to notice the bungee tighten and resist against you (depending on the length of your pool, you may need to wrap the bungee around the supporting object or tie it in knots to make it shorter to feel resistance).

Spend a few moments testing yourself to see how far you can pull the bungee.

This is a great challenge and a fun way to compete with yourself during an otherwise boring cross training activity.

Now for the hard part:

Pick a point on the pool wall or side of the pool that you feel stretches the bungee to a very hard sprint that you could maintain for 60-90 seconds.

This will be your “sprint” marker that you’ll use on sprint intervals (95-100% of maximum heart rate or all out sprint).

Now:

Find a point that feels like the end of a hard tempo run.

Mark this spot as your “medium” interval distance.

When you complete the hard workouts, you can use these reference points to ensure that you maintain a very hard effort.

The springboard

10 minutes easy warm up, 90 seconds easy (slowly moving out and stretching the bungee), 2 minute medium, 1 minute sprint, 1 min rest (let the bungee pull you back – this is kind of fun). Repeat 10 times. 10 minutes easy cool down.

The race simulation

10 minutes easy warm up, 90 seconds easy (slowly moving out and stretching the bungee), 5 minutes medium (focus and concentrate, just like during the hard part of a race), 30 seconds sprint, 2 minutes rest. Repeat 4 times. 10 minutes easy col down

The lactic acid

10 minutes easy warm up, 90 seconds easy (slowly moving out and stretching the bungee), 2 minutes sprint, 90 seconds rest. Repeat 12 times, 10 minutes easy cool down.

I guarantee that with the bungee, you’ll get your heart rate through the roof.

You can challenge yourself and make aqua jogging more fun by seeing how long you can stay at your maximum stretched distance or seeing how far you can push it.

Likewise, if you have a friend who is injured (or someone willing to be a good sport) you can try pulling each other across the pool for some competitive fun.

Cross training can be tough, especially when you’re injured or want to be increasing your volume faster.

However, I hope that providing a variety of workouts, either through the Fluid Running app (which also makes it easier to keep track of the workout while in the water) or on your own can add a fun challenge in the pool and you can emerge from your injury with minimal fitness loss.

Time off and return to running

Unlike stress fractures or tendon injuries, where there are fairly well-researched and understood protocols for how long you should take off and how quickly you can return to running, there’s a lot more variability with calf strains.

You may only need a few days off if you’re young and had a mild overuse strain, but an acute or severe strain in an older runner could require several weeks off from running.

Ultimately, pain will have to be your guideline.

You’re bound to have an initial period where your calf is stiff and painful; this is when you should definitely avoid running. Hit the pool or get on the bike, so long as it doesn’t aggravate your calf.

Once the initial aggravation has calmed down, you can start heating and foam rolling the area a few times a day to loosen up any tight muscle tissue. This is also when you should start doing strength exercises to rehabilitate the muscle.

Once walking around feels okay for a day or two, you can give running a shot. Be aware that you’ll have to ease back into things, and you should avoid faster running, low-heeled shoes, and steep uphills for a while.

If it’s taking longer than expected for your calf to heal, consider seeing a physical therapist to identify any biomechanical faults, or an ART or Graston Technique practitioner to loosen up any scar tissue or muscular adhesions that might be causing continued pain.