Find a training program that works for you is an essential component to achieving your goals. Not only do you need to find a plan that fits with your individual strengths and weaknesses, but you need to believe strongly in the philosophy behind the plan.

My biggest mistake early in my running career was believing I knew it all. As such, I never put my full faith in the training philosophy of my coach.

I thought there was a better way, I’d get caught up in the latest “fad” training idea, and I always wanted more mileage and harder workouts.

The problem with this approach is that it’s short-sighted.

I focused on the immediate aspects of one “training system” but didn’t try to think long-term about the philosophy – how did things fit together, how did it compare, what were the strengths and weaknesses.

Once I understood this, I was able to better compare specific training philosophies and training plans and find what worked for me. When that happened, I developed the trust in the system that allowed me to record new PRs after months of bad races.

As a coach now, I am frequently asked how our training philosophy and training schedules at RunnersConnect compare to some of the other well-known and popular training plans available.

This is a great question because I believe, like I was in my own training, you can only be truly successful if you believe in the plan. Having faith in your plan and understanding its nuances helps build confidence in your fitness and abilities.

In this article, I am going to outline the differences between our training philosophy or approach to specific race distances and some of the more popular plans or programs available.

Since this is going to be quite long (and have some repetitive content) my suggestion is to jump to the race distance you’re most interested in learning about.

5k and 10k training comparisons

Half Marathon training comparisons

Marathon training comparisons

Some notes before we get started:

1. I can only compare our philosophy to those I know well, have studied, or worked under myself. If I don’t mention a coach/program specifically, let me know in the comments and I can try do some research. However, the plan must be publically available in some way.

2. It’s important to remember when comparing any two training philosophies that there isn’t only one way to train. While there are certainly training concepts that apply universally, the specifics of how to approach a race can be different. Obviously, each coach believes in their system.

3. If you have no intention of ever using us as coaches, that’s ok. I still think this can be a valuable read as you’ll get to learn different approaches to training and definitely some ideas you can implement in your own plan.

4. This comparison is in no means written as a way to besmirch any of the following plans or coaches. I actually really like some of them. It’s simply a means to compare our differing approaches to the same goal – helping you run faster.

5. Finally, I have no doubt that for the plans mentioned below that offer personalized coaching options they would accommodate your needs. This is simply a comparison of philosphies based of generally available plans and literature produced.

Ready to get started? Jump to your favorite race distance…

5k and 10k training comparisons

Half Marathon training comparisons

Marathon training comparisons

5k and 10k training comparisons

First, it’s helpful if you know our overall approach to training so you have something to compare it to if you’re not currently coached by us.

The RunnersConnect philosophy

From general to specific

Our overall approach to 5k and 10k training is that as a runner gets closer to race day, we want their workouts and training to become more and more specific to the demands of the race.

This progression is generally called “general to specific”. In essence, your training is split into two these two phases – general and specific.

Phase 1: The general phase occurs at the start of your training cycle and is designed to slowly build each energy system to its highest fitness before starting the race specific phase.

During the general phase you slowly build upon each component (speed, strength, long run, mileage) so that no particular energy system is left behind. You start at whatever fitness level you’re at and by the end of the training cycle, your aerobic development, speed, and threshold are at their maximum levels simultaneously. Here’s a good way to visualize how this works:

The general phase can also be broken down into subsections with a particular focus. For example, if you’re a little weak on speed, workouts can have a more speed development focus whereas if you need to develop your aerobic system, you can target more threshold runs in this phase

Phase 2: The race specific phase is typically 6-8 weeks long, depending on your fitness level and training history. It occurs directly after the general phase and comprises the last 6-8 weeks of your training before the race.

As the name implies, race-specific training means training to the specific physiological demands of your race distance.

In a 5k and 10k specific training phase, your goal should be to improve your speed endurance – your ability to maintain and hold a fast pace for the entire race. The more you can develop and target this system, the faster you will be able to race.

In almost all runners we coach, our goal is to build them up to their highest level of overall running fitness during the general phase and then target their training specifically in the final 6-8 weeks.

Focus on aerobic development

The major mistake most runners make when training for the 5k or 10k is neglecting the aerobic system. Many of us view the 5k and 10k as “speed training”, yet the aerobic system plays a pivotal roll in 5k and 10k performance.

You can see from the research summarized in this chart that the aerobic system comprises 85-90% of the energy demands for a 5k or 10k race:

More importantly, development of the aerobic system is the single most important factor for long-term progress.

Therefore, for both short-term and long-term gains, we try to build as much aerobic work into your training plan as possible through long runs, targeting the right easy paces, and ongoing threshold work.

Speed endurance more important than speed development

From a training standpoint, speed is rarely the limiting factor in how fast you can race, even for a distance as “short” as the 5k. Yet, when most runners approach us for help improving their PRs at shorter distances they almost always tell us they need to “work on their speed”. But is this really the case?

Let’s use an example: If you want to run 20 minutes for the 5k (or use your own 5k goal), you need to average 6:25 pace per mile. Technically, that means the fastest pace you need to be able to run is 6:20 per mile.

If you’re currently a 21-minute 5k runner, I have little doubt you can run a 6:20 mile; you’re probably capable of running a mile close to sub 6 minutes.

Thus, the problem isn’t that you don’t have enough speed to run a 20-minute 5k, it’s that you lack the endurance to run three 6:25 miles without stopping.

This is what we call speed endurance – your ability to maintain and hold a fast pace for the entire race – and it’s the major focus of your race specific phase.

That’s not to say we ignore speed development all-together. Like I discussed in the section on the purpose of the general phase, it’s important to touch on all training systems throughout a training cycle.

We definitely include speed development workouts in 5k and 10k training. However, we also “sneak” speed development work into the plan by including strides, hill sprints, drills and other subtle, yet effective speed development training elements.

Hopefully, that helped give you an overview of our philosophy and how our plans are structured. If you feel we could be more in-depth, let us know in the comments section or join our upcoming 5k and 10k training webinar and see the plan in action with specific workouts.

Hal Higdeon, RunnersWorld, Active 5k/10k plans

Most of these 5k and 10k plans on these three sites are designed the exact same way; if you looked at each of these plans on a calendar, it would be difficult to tell them apart.

Again, not that this is wrong. These plans all follow the same philosophy and thus they should look very similar (which is why I have grouped them together here).

The Hal Higdeon, RunnersWorld and Active plans typically only provide the final 6-8 weeks of training. Therefore, I can’t comment too specifically on how they approach the build-up to these workouts or what the philosophy is long-term.

Overall plan structure

The overall philosophy of these three plans is a pretty basic, old-school training structure: One VO2max or speed session early in the week, a tempo session the second half of the week, a fast run on Saturday and a long run on Sunday.

The plans use the same pattern week-after-week, with the same exact workouts, incrementally increasing the mileage of each workout through the cycle.

While I find this approach ignores both the concept of periodization and race-specific training, I think it’s actually helpful for beginners who are intimidated by workouts late in a training cycle.

Most beginners get a plan and immediately look at the final few weeks of the schedule. When the workouts look complicated (as race-specific workouts do) or it’s not clear how you’re building to do them (as is the case with periodization) it’s very intimidating. The approach these plans use makes it very clear how you’re going to take the next step each week. In essence, it makes it very easy to have confidence in these plans, which is a definite plus for new runners.

In addition to a focus on race-specific workouts in the final 6-8 weeks, our approach tries to incorporate a variety of of workouts to attack your physiological systems from different angles.

As an example, I believe there are three types of thresholds – aerobic threshold, lactate threshold, and anaerobic threshold. While a “tempo” run can mean targeting any of of these three subtly different systems, I prefer to specifically attack each one with different types of workouts. We incorporate cutdowns, alternating tempos, lactate clearance tempos, and steady runs.

Not only does this add variety, but I find it helps strengthen specific physiological systems more distinctly and allows for better long-term progression.

Speed versus speed endurance

As discussed in-depth above, I believe speed workouts should focus more on speed endurance rather than pure speed or VO2 max and it’s a major difference in our approach to training for the 5k and 10k.

Speed endurance workouts improve the speed component of 5k or 10k fitness, but don’t specifically target your ability to hold a fast pace for an extended period of time, which I believe is the critical piece to racing faster.

To further expound on this idea, lets compare a traditional interval workout to a speed endurance workout.

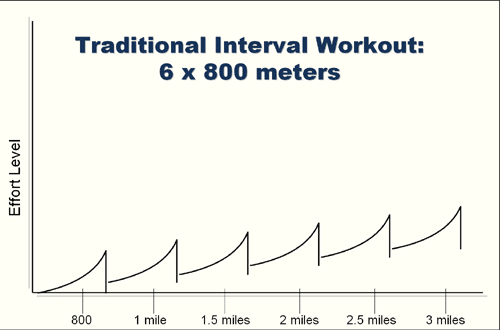

One problem with traditional interval workouts that are run at a consistent pace is that the recovery between those intervals allows the athlete to recover to a state that is very unlike the corresponding point in a race. To illustrate this concept, here is what the effort levels of a typical interval workout looks like:

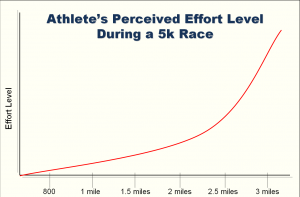

However, we know that’s not how you typically feel or what you experience during a 5k race. In reality, you need to increase your effort as the race continues, adapt to increasing levels of fatigue, and to push through the discomfort.

Unlike a traditional interval workout shown above, running goal pace in mile 2 doesn’t require the same effort as mile one. To illustrate this point, here is a graph of what a typical race effort feels like:

What we need to do is train your body how to run goal pace while tired, under duress, and without the extended rests that allow you to fully recover.

That’s why a workout like 6 x 800 meters at goal race pace with 200 meters quick jog rest is far more race-specific than a traditional VO2max workout.

In this instance, you’re teaching yourself how to run 5k pace with as little rest as possible. By not fully recovering and jogging quickly between repeats you still improve your ability to run at race pace, but you ensure you have the aerobic strength and support to maintain goal pace on race day.

In short, lots of runners have found success with these basic plans and I think they can be a great starting point. But, if you want to take your race times up a notch, you simply must include race-specific training and start thinking about the demands of the race distance.

McMillan 5k and 10k training comparison

McMillan doesn’t offer too many free plans or samples we can use, but luckily I have worked with enough athletes who’ve used his plans and I have read many of his articles, so I think I have a good grasp on his training philosophy.

The pyramid model

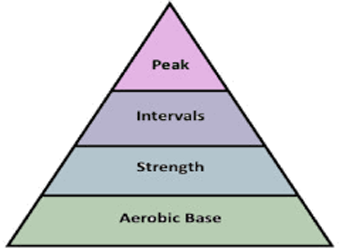

The main difference between RunnersConnect and McMillan is how we approach the phases of training. McMillan envisions the base or general phase like a pyramid. The pyramid model is based on the idea that you begin with a large aerobic base, transition to strength work such tempo runs and hill work, add in speed work, and then peak at the end of the training cycle. Here’s a good illustration:

McMillan’s methods and this pyramid idea are based mostly off the Lydiard system, which has been shown to be highly successful, specifically because of it’s focus on aerobic development.

However, my main argument against the pyramid model is the notion that aerobic development, lactate threshold, and speed have to be trained independently of each other.

I believe, if done correctly, you don’t have to run months of just mileage or taper off your tempo runs as you introduce speed work.

Second, when you train using the typical pyramid model, you’re forced to revert back to a base building period after each training cycle and you lose many of the of the strength and speed gains you’ve made at the top of the pyramid. Therefore, you spend a good portion of your next training cycle just trying to get back to that level of speed and strength, instead of constantly improving the current point that you’re at.

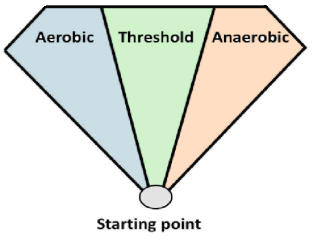

My approach is to use what we call the “diamond” model in the general phase, which is designed to slowly build each energy system to its highest fitness before starting the race specific phase.

During the general phase you slowly build upon each component (speed, strength, long run, mileage) so that no particular energy system is left behind. You start at whatever fitness level you’re at and by the end of the training cycle, your aerobic development, speed, and threshold are at their maximum levels simultaneously. Here’s a good way to visualize how this works:

The general phase can also be broken down into subsections with a particular focus. For example, if you’re a little weak on speed, workouts can have a more speed development focus whereas if you need to develop your aerobic system, you can target more threshold runs in this phase. When doing this, I think there are ways to target both or multiple systems, for example by doing a combo workout (tempo run followed by interval work).

Finally, as discussed above, rather than “sharpening” at the top of the pyramid, the RunnersConnect philosophy is to continually get closer and closer to the specific demands of the race with each workout.

Here’s a sample 6 week ADVANCED progression we might use (this is just the 5k specific work, not the tempo, mileage or long runs and is obviously not customized):

- Week 1: 2-3 mile warm-up, 11 x 400 meters at 5k goal race pace with 100m jogging rest, 1-2 mile cool down

- Week 2: 2-3 mile warm-up, 8 x 600 meters at 5k goal race pace with 100m jogging rest, 1-2 mile cool down

- Week 3: 2-3 mile warm-up, 6 x 800 meters at 5k goal race pace with 200m jogging rest, 1-2 mile cool down

- Week 4: 2-3 mile warm-up, 12 x 400 meters at 5k goal race pace with 100m jogging rest, hammer #10 as fast as you can, 1-2 mile cool down

- Week 5: 2-3 mile warm-up, 8 x 800 meters at 5k goal race pace with 200m jogging rest, hammer #6 as fast as you can, 1-2 mile cool down

- Week 6: Race week 2-3 mile warm-up, 2 x 1 mile at 3k-5k pace w/5 min rest, 2 x 400 meters at mile pace w/3 minutes rest, 2 mile cool down.

Summary

In summary, I have no qualms with McMillan’s training philosophy. I think it’s great for long-term development and has a proven track record. There is definitely more than one way to train.

I think the only potential downside is that most runners these days participate in a lot of different races during their training cycle, even when they have 1 or 2 big goal races at the end. Personally, I’ve found that the base structure of the pyramid makes it very difficult to race well as you build up. This is totally find for elite runners who are training for a big championship race and are generally fast enough to run well all the time.

On the other hand, using the diamond model allows you to be as fit (generally) as you can be and thus better able to perform for these tune-ups. I think it gives you more confidence and allows you to have more consistent results across the board.

Hudson training systems

Hudson’s training methods and the approach we take here at RunnersConnect are very similar. We both believe that training should progress each cycle from general to specific.

Moreover, as discussed in my comparison to McMillan we both believe that it’s advisable to train all of the systems simultaneously in the general phase to develop overall as a runner.

Perhaps the only difference in how Hudson approaches 5k and 10k training and what we do at RunnersConnect is how long the race specific phase lasts. Generally, Hudson works with more experienced elite runners. As such, they have a larger capacity for work – mileage, long runs, speed workouts. It’s easier for them to jump into a workout like 4-5 x 2000 meters with 3 minutes rest at goal 10k pace without getting hurt or overdoing it.

Generally speaking, I prefer to build-up to these workouts more gradually. Therefore, because we need to start further back (this would obviously be specific to the athlete) we need more weeks in the race specific phase to build to the pinnacle workouts.

Summary

If you’re an advanced runner, you’ll do very well with the Hudson or RunnersConnect approach. They are both modern training plans that implement some of the latest information we’ve learned as coaches.

However, I find the Huson plan to be very aggressive for beginner or intermediate runners. Surely, some can handle it, but it’s important to modify the workouts to your current ability levels (and as noted at the start, if you were coached by Brad he would surely modify them for you – he hates template plans about as much or more than I do).

Half marathon training philosophy

First, it’s helpful if you know our overall approach to half marathon training so you have something to compare it to if you’re not currently coached by us.

The RunnersConnect philosophy

Our overall approach to training is that as a runner gets closer to race day, we want their workouts and training to become more and more specific to the demands of the race. This progression is generally called “general to specific”. In essence, your training is split into two these two phases – general and specific.

From general to specific

The general phase occurs at the start of your training cycle and is designed to slowly build each energy system to its highest fitness before starting the race specific phase.

During the general phase you slowly build upon each component (speed, strength, long run, mileage, etc.) so that no particular energy system is left behind. You start at whatever fitness level you’re at and by the end of the training cycle, your aerobic development, speed, and threshold are at their maximum levels simultaneously. Here’s a good way to visualize how this works:

The general phase can also be broken down into subsections with a particular focus. For example, if you’re a little weak on speed, workouts can have a more speed development focus whereas if you need to develop your aerobic system, you can target more threshold runs in this phase

The race specific phase is typically 6-8 weeks long, depending on your fitness level and training history. It occurs directly after the general phase and comprises the last 6-8 weeks of your training before the race.

As the name implies, race-specific training means training to the specific physiological demands of your race distance.

In a half marathon specific training phase, your goal should be to develop your lactate threshold, improve your ability to clear lactate, and increase your speed endurance. The more you can develop and target these systems, the faster you will be able to race.

In almost all runners we coach, our goal is to build them up to their highest level of overall running fitness during the general phase and then target their training specifically in the final 6-8 weeks.

Focusing on the specific demands of the race

For the advanced runner, the physiological demands of the half marathon require that you train yourself to be able to run at the top end of your lactate threshold for increasingly longer periods of time.

This is accomplished by improving your lactate threshold itself, teaching your body how to clear lactate back into usable energy more efficiently, and increasing your speed endurance. I believe the more you can perform workouts that target these specific systems in the final 8 weeks of training the faster you will run.

For beginner runners just looking to finish the distance, the amount of time spent running is the most important factor in training.

Research shows that biological markers of muscle fatigue (aspartate aminotransferase (AST), creatine kinase (CK), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and myoglobin) increased significantly immediately after a half marathon and remained elevated for more than 24 hours thereafter. To put it simply, when you’re running for close to two hours, you’re putting a tremendous stress on the muscles in your legs and you have to prepare your body for this challenge in training.

To do so, I believe the focus for beginner runners should be on increasing their overall mileage, their long runs and increasing the total amount of miles they do each week at half marathon pace.

Hopefully, that helped give you an overview of our philosophy and how our half marathon plans are structured. If you feel we could be more in-depth, let us know in the comments section or join our upcoming half marathon training webinars and see the plan in action with specific workouts.

Hal Higdeon, RunnersWorld, Active 5k/10k plans

Most of these half marathon plans on these three sites are designed the exact same way; if you looked at each of these plans on a calendar, it would be difficult to tell them apart.

Again, not that this is wrong. These plans all follow the same philosophy and thus they should look very similar (which is why I have grouped them together here).

Overall plan structure

The overall philosophy of these three plans is a pretty basic, old-school training structure: One VO2max or speed session early in the week, a tempo session the second half of the week, a faster run on Saturday and a long run on Sunday.

The plans use the same pattern week-after-week, with the same exact workouts, incrementally increasing the mileage of each workout through the cycle.

While I find this approach ignores both the concept of periodization and race-specific training, I think it’s actually helpful for beginners who are intimidated by workouts late in a training cycle.

Most beginners get a plan and immediately look at the final few weeks of the schedule. When the workouts look complicated (as race-specific workouts do) or it’s not clear how you’re building to do them (as is the case with periodization) it’s very intimidating. The approach these plans use makes it very clear how you’re going to take the next step each week. In essence, it makes it very easy to have confidence in these plans, which is a definite plus for new runners.

That being said, I still think it’s important to include a variety of workouts in a training plan to attack your physiological systems from different angles.

As an example, I believe there are three types of thresholds – aerobic threshold, lactate threshold, and anaerobic threshold. While a “tempo” run can mean targeting any of of these three subtly different systems, I prefer to specifically attack each one with different types of workouts. We incorporate cutdowns, alternating tempos, lactate clearance tempos, and steady runs.

When trying to reach your peak and absolute best, attacking your physiological systems with many different stimuli is critical. A basic tempo run performed at the same pace each week targets the same energy system with no additional or new stimulus. Training like this would be akin to going to the gym and only doing straight bicep curls to help get bigger arms. The body will respond initially, but will quickly plateau.

Lack of race-specific training

As mentioned in the section on our training philosophy, I believe one of the keys to maximizing your performance is performing race specific workouts in the final 6-8 weeks of training. Doing workouts that don’t specifically target the demands of your goal race are not as effective as they could be.

As an example, the half marathon requires you to run on the edge of your lactate threshold and is a test of your ability to quickly clear lactate while running at a pace that is just above comfortable. Moreover, you need to train your legs to endure running hard for 13.1 miles.

So, how does a workout such as 5 x 800 meters at 10k pace 3 weeks before your goal race (a sample workout from Hal Higdon’s advanced plan) train you to do this? It doesn’t.

A better speed workout would be 5-8 miles (depending on experience level) at slightly faster then goal half marathon pace with a short, jogging recovery. Now you’re teaching your body how to run fast while tired and with little rest – basically what you’ll experience during the race.

An even better workout would be something like 6-8 miles alternating between slightly faster than marathon pace and slightly slower than 10k pace. This workout is called an alternating tempo and teaches your body how to clear lactate efficiently – precisely what you need to do during the race to finish faster and stronger.

Lack of aerobic development

Another flaw in the Hal Higdon approach is the lack of focus on aerobic development.

But, why is the aerobic system so important and why don’t Higdon programs improve it?

In any event longer than 5k, the aerobic system contributes more than 84% of the energy required to run the race. In the marathon, that number is 99%. Here’s the data if you don’t believe me.

That means to run your best at longer distances from 5k to the marathon you need to fully develop your aerobic system.

So, how do you develop the aerobic system? With slow, easy runs. If you’re curious, I outlined in great depth what the aerobic system is and exactly how easy runs develop it here. I highly recommend reading that article if you haven’t already.

The problem with the Hal Higdon method is that easy running is a very small portion of the plan. That means you’ll spend less of your training time working on the energy system that contributes 95% of the energy required to run a fast half marathon.

But doesn’t running more lead to injury?

Most runners have an irrational fear that mileage is a primary cause of running injuries. While I’m certain drastically increasing weekly mileage totals play a role in the likelihood of running injuries, my experience and research has shown that too much intensity is a far more likely reason you might get injured.

Intensity (or speed work) increases your chances of getting injured because it places a far greater stress on your structural system (muscles, tendons, ligaments and bones) than easy running.

For example, you may be able to head out the door and hammer out a long run or a tempo run at 8 minutes per mile (or whatever your tempo pace is), but your hips might not be strong enough yet to handle the stress of the pace and, as a result, your IT band becomes inflamed.

If you progressively and slowly build your mileage while adding the appropriate ancillary work you can handle more miles, train your aerobic system to be stronger, and continue to improve year after year.

Marathon training philosophy

From general to specific

Our overall approach to training is that as a runner gets closer to race day, we want their workouts and training to become more and more specific to the demands of the race. This progression is generally called “general to specific”. In essence, your training is split into two these two phases – general and specific.

The general phase occurs at the start of your training cycle and is designed to slowly build each energy system to its highest fitness before starting the race specific phase.

During the general phase you slowly build upon each component (speed, strength, long run, mileage, etc.) so that no particular energy system is left behind. You start at whatever fitness level you’re at and by the end of the training cycle, your aerobic development, speed, and threshold are at their maximum levels simultaneously. Here’s a good way to visualize how this works:

The general phase can also be broken down into subsections with a particular focus. For example, if you’re a little weak on speed, workouts can have a more speed development focus whereas if you need to develop your aerobic system, you can target more threshold runs in this phase

The race specific phase is typically 10-12 weeks long, depending on your fitness level and training history. It occurs directly after the general phase and comprises the last 10-12 weeks of your training before the race.

As the name implies, race-specific training means training to the specific physiological demands of your race distance.

In a marathon specific training phase, your goal should be to develop your aerobic threshold, improve your ability to burn fat as a fuel source when running at marathon pace, and increase your muscular endurance. The more you can develop and target these systems, the faster you will be able to race.

In almost all runners we coach, our goal is to build them up to their highest level of overall running fitness during the general phase and then target their training specifically in the final 10-12 weeks before their marathon.

Aerobic threshold

Imagine you are a hybrid car. Your muscles are the engine, glycogen the gas power and fat electric power. Just like a car, you can run using both glycogen and fats depending on how hard you need to work. And, similar to a car, your personal gas tank holds a finite amount of gas (glycogen). Fully carbo-loaded, you can store 1320kcal to 2020kcal glycogen in your liver, muscles and blood combined.

Depending on your size and fitness, running utilizes about 1kcal/Kg/Km. Let’s say you weight 175 pounds (80kg) you need about 3360 kcals (80kg x 42 km) to make it through the race.

Therefore, the stored amount of glycogen of 1320 to 2020kcal is far less than the 3360kcal needed to finish the race. Since it’s impossible to eat 2000 calories during the race, we need to find a way to conserve gas (glycogen) and run as efficiently as possible on electric (fats)

Like a hybrid car, the faster you run, the more you need to rely on gas (glycogen). Luckily, running aerobically requires only a little gas and is mostly electric. But, if you just run very easy, you’re not likely to finish in a time you’re happy with. So, we need to find that optimal balance between electric (fat burning) and gas (glycogen burning) that allows you to get to the finish as quickly as possible.

Aerobic threshold is defined as the fastest pace you can run while using the aerobic system as the primary energy pathway

In essence, aerobic threshold is that optimal pace between fat and glycogen usage. Thus your marathon pace, and thus your finishing time, is directly correlated with your aerobic threshold.

Burning fat as a fuel source

The problem with using fat as an energy source is that it’s not a very efficient provider of energy. It takes a while for your body to be able to oxidize fat into usable energy for the body. The faster you want to go (and thus the more energy your muscles demand) the less efficient fat becomes.

However, you can train your body to become more efficient at burning fat as a fuel source. This can occur by targeting this system specifically with workouts/mileage, the way you structure your workouts and long runs, as well as your nutrition.

The big mistake I see a lot of runners make is not paying any attention to improving their ability to burn fat as a fuel source in training. They either don’t know about it, are following antiquated training methods, or are simply given wrong information.

Our marathon training philosophy is designed around training this specific system as often as possible in training. I don’t often see other training systems with this goal.

Improving muscular endurance

The final big piece of the puzzle is muscular endurance. You can have all the glycogen in the world, but if your muscles are not up to the task of running 26.2 miles, you’re going to have a crappy race.

The challenge is that running the full marathon distance in training is not recommended (due to how long it would take to recover). So, we need to get creative in training to simulate the fatigue and develop the muscular endurance needed.

To accomplish this, we can do two things:

First, we can implement what coaches call the theory of “accumulated fatigue”. Basically, this means that the fatigue from one workout accumulates and transfers to the next so that you’re always starting a workout or a long run a little tired from your previous training. This type of training helps your develop the muscular endurance without needing to run the full marathon in training.

Second, you can implement specific workouts that are designed to fatigue your legs and muscle and then have you train and run at marathon pace. The nice thing about these workouts is that they occur all in one session and can help simulate different types of fatigue you’ll experience on race day.

Long runs

As you may already know, I tend to believe that most runners and training schedules overemphasize the long run. Here’s why I think that is a critical flaw and how we approach things instead:

As we’ve discussed already, the primary goals of training should be to increase aerobic threshold, utilize fat more efficiently at marathon pace, and build endurance. So where does the marathon long run fit in with these 3 goals?

Aerobic threshold

Research has shown that your body doesn’t see a significant increase in aerobic development, specifically mitochondrial development, after you’ve been running for 2 hours. As a 3:45 marathoner, your easy long run pace is likely between 9:30 and 10:00 mile. So, a 20-22 miler will take you a little over 3 hours to finish.

Moreover, running all easy pace, which you’ll need to do to run for 22 miles in the middle of training, never challenges your aerobic threshold. Not one mile trains you to run at aerobic threshold. You can’t improve an energy system if you never train it.

Compare this to what we suggest, which is instead running 16-18 mile long runs with a 4-5 mile fast finish (at marathon pace).

The total time running will be closer to 2:30, which still provides the aerobic development you need and is similar in comparison to a 20-miler due to how aerobic development flat lines after 2 hours. More importantly, you spend 4-5 miles running at aerobic threshold (while tired).

The added benefit is that reducing your long run volume makes you less susceptible to injury and reduces your recovery time. This allows you to be more consistent, remain injury-free, and have the energy to perform marathon-specific workouts and more mileage through the week. When running a 20-22 miler, it takes you almost all week to recover so you never have a chance to do the race-specific work you need.

Fat utilization

It’s easy for your body to burn fat as a fuel source when running easy. However, to teach your body how to burn fat as a fuel as a fuel source you need to run at marathon pace while you’re already low on glycogen. This forces the body to use fat as a fuel source (at marathon pace) and therefore become more efficient at doing so.

20-22 miles of all easy running = 0 miles training to burn fat while running at marathon pace

16-18 miles with a 4-5 mile faster finish = 4 to 5 miles training to utilize fat as a fuel source while running at marathon pace.

Endurance

Yes, running 20-22 miles is good for muscular endurance. But, the longer you run, the more you susceptible to injuries you become. Your form begins to break down, your major muscles become weak (thus relying on smaller, less used muscles), and overuse injuries begin to take their toll.

Moreover, you never run at marathon pace while tired. So, your muscular endurance is improved while running easy, but not when trying to run at marathon pace, which requires different recruitment of muscle fibers. This approach is not very specific to what you’ll experience on race day and why your body isn’t capable of pushing through it.

Compare this to the muscular fatigue from a 16-18 miler with a fast finish.

You get 4-5 miles of running at marathon pace while tired.

Moreover, our long run philosophy is to always buttress the long run against a steady run the day before. For example, you may run 1 mile easy, 6 miles marathon pace, 1 mile easy on Saturday and then run your full long run on Sunday. Because of the harder running on Saturday, you start Sunday’s long run not at zero miles, but rather at six or eight miles, since that is the level of fatigue and glycogen depletion your body is carrying over from the previous run.

Compare our long run approach to the traditional 20-22 mile easy approach

Total miles at MP = 0. Total miles for weekend = 22

Total miles at MP = 11. Total miles for weekend = 26

Hal Higdeon

Of all popular training programs, I’d say Hal Higdeon is probably most different from our training philosophy. The two main differences are the focus (or lack thereof) of race specificity and the emphasis on long runs.

Race specificity

Our overall approach to training is that as a runner gets closer to race day, we want their workouts and training to become more and more specific to the demands of the race. In a marathon specific training phase, your goal should be to develop your aerobic threshold, improve your ability to burn fat as a fuel source when running at marathon pace, and increase your muscular endurance. The more you can develop and target these systems, the faster you will be able to race.

In Hal Higdeon’s programs, I believe the idea of race specificity is somewhat ignored. The mid-week workout rotates between hill repeats, 800 intervals and basic tempo run. In my view, that’s a lot of VO2max and interval training for an event which relies very little on these two physiological elements.

Since the marathon requires running at your aerobic threshold and burning fat efficiently as a fuel source at marathon pace, I believe swapping these workouts with lactate clearance runs, steady state efforts, and other more marathon-specific workouts makes better use of the mind-week workout day.

Long runs

Hal Higdeon’s plans follow the traditional marathon philosophy of running multiple slow, easy 20 milers. As you may already know, I tend to believe that long, slow easy runs are overrated, especially for those running over 3:30 minutes or who are running less than 50 miles per week.

Research has shown that your body doesn’t see a significant increase in aerobic development, specifically mitochondrial development, after you’ve been running for 2 hours. As a 3:45 marathoner, your easy long run pace is likely between 9:30 and 10:00 mile. So, a 20 miler will take you a little over 3 hours to finish.

Moreover, running all easy pace never challenges your aerobic threshold. Not one mile trains you to run at aerobic threshold. You can’t improve an energy system if you never train it.

Finally, research has also shown that the longer your long runs, the greater your chance of injury. By reducing your long runs (and getting more marathon specific) you can reduce injury risk and recovery time (allowing you to do more mileage and marathon-specific workouts during the week).

Our approach is to use marathon specific long runs, such as fast finish long runs and surge long runs, to better simulate the specific demands of the race while reducing wear and tear.

As an example, it’s easy for your body to burn fat as a fuel source when running slow (the energy demand isn’t high). However, to teach your body how to burn fat as a fuel source at marathon pace, you need to run at marathon pace while you’re already low on glycogen. This forces the body to use fat as a fuel source (at marathon pace) and therefore become more efficient at doing so.

20 miles of all easy running = 0 miles training to burn fat while running at marathon pace

16-18 miles with a 4-5 mile faster finish = 4 to 5 miles training to utilize fat as a fuel source while running at marathon pace.

I’ll admit, running 20 miles is good for muscular endurance. But, you never run at marathon pace while tired. So, your muscular endurance is improved while running easy, but not when trying to run at marathon pace, which requires a different recruitment of muscle fibers. This approach is not very specific to what you’ll experience on race day and why your body isn’t capable of pushing through it.

Compare this to the muscular fatigue from a 16-18 miler with a fast finish.

You get 4-5 miles of running at marathon pace while tired.

Hansons plan

Having spent a few years training with the Hansons, a good portion of our marathon training philosophy echoes the Hansons plan. Specifically, as outlined above, we believe that the long run is an integrated part of the training, rather than a specific number you need to hit, and the volume needs to correspond to your weekly mileage. Likewise, we believe that overall mileage and marathon specific work is the key to running your best – not long, slow 20 milers.

Our approach to the marathon differs mainly in how we approach the long runs.

Our harder long runs are always preceded by a steady run (marathon paced run) the day before. The volume of this run depends on experience level and mileage. In addition, long runs almost always contain some type of faster running – fast finish or surges.

The goal of the steady run the day before the long run is to capitalize on accumulated fatigue. By running marathon pace the day before the long run, you lower your glycogen stores and fatigue the legs in a very marathon-specific fashion so that you’re essentially starting the long run with miles already in your legs.

Don’t get me wrong, the Hansons plan has the same goal – I just think adding the steady the day before is more specific. Plus, the extra stimulus is needed to help boost the shorter long run for more overall quality throughout the weekend.

We also have a few workouts and long runs the Hansons plans don’t have, which I think help with marathon-specific readiness. For example, we include what we call “marathon surges” which are an innovative way to help teach your body to burn fat as a fuel source while running at marathon pace. These types of workouts can help you conserve glycogen and prevent bonking.

Finally, I also find the Hansons plan structures training on goal marathon pace (and 10 seconds faster) rather than current physiological fitness. While this distinction seems slight, I think it’s critical and something most runners get wrong.

In order for you to become fitter, you need to run in the right effort and pace zones. For example, if your goal is to run a 3:10 marathon, then under the Hansons plan you’ll be doing marathon pace runs at 7:15 or 7:05 pace. However, if your physiological fitness level is actually 3:20 for the marathon, then 7:40 pace is your physiological aerobic threshold (marathon pace). Running 7:15 or 7:05 pace turns this workout into a high end threshold run rather than an aerobic threshold run. As such, you’ll have run 0 miles at aerobic threshold. Sure, your overall running fitness will improve, but your marathon specific fitness won’t.

McMillan

The main difference between RunnersConnect and McMillan is how we approach the phases and progression of training.

McMillan envisions the base or general phase like a pyramid. The pyramid model is based on the idea that you begin with a large aerobic base, transition to strength work such tempo runs and hill work, add in speed work, and then peak at the end of the training cycle.

McMillan’s methods are based mostly off the Lydiard system, which has been shown to be highly successful, specifically because of it’s focus on aerobic development.

However, my main argument against the pyramid model is the notion that aerobic development, lactate threshold, and speed have to be trained independently of each other. I believe, if done correctly, you don’t have to run months of just mileage or taper off your tempo runs as you introduce speed work.

Second, when you train using the typical pyramid model, you’re forced to revert back to a base building period after each training cycle and you lose many of the of the strength and speed gains you’ve made at the top of the pyramid. Therefore, you spend a good portion of your next training cycle just trying to get back to that level of speed and strength, instead of constantly improving the current point that you’re at.

My approach is to use what we call the “diamond” model in the general phase, which is designed to slowly build each energy system to its highest fitness before starting the race specific phase.

During the general phase you slowly build upon each component (speed, strength, long run, mileage) so that no particular energy system is left behind. You start at whatever fitness level you’re at and by the end of the training cycle, your aerobic development, speed, and threshold are at their maximum levels simultaneously. Here’s a good way to visualize how this works:

The general phase can also be broken down into subsections with a particular focus. For example, if you’re a little weak on speed, workouts can have a more speed development focus whereas if you need to develop your aerobic system, you can target more threshold runs in this phase

Pfiztiger

Pftzinger seems to follow a very “traditional” marathon formula, which is quite different from how we approach the marathon and is similar to the McMillan marathon training approach.

First, Pfitzinger begins the training plan with lactate threshold workouts and transitions to VO2max workouts as the race gets closer. This is the more traditional pyramid structure I discussed earlier with McMillan.

As you might remember from the outline of the Hal Higdeon approach, our marathon philosophy is focused on marathon-specificity. Particularly, I believe that the closer you get to race day, the more specific your workouts need to be to the demands of the marathon distance – handling the volume, burning fat as a fuel source at marathon pace, and improving aerobic threshold.

In the Pftizinger plan, you’re actually getting farther away from marathon specify as you get closer to the race. You’re working on your VO2max and anaerobic capabilities, which have little bearing on your marathon performance.

Second, weekly mileage seems to be a large component of Pfitz plans – it’s almost how you select your plan. I feel that mileage itself needs to be individualized to the runner – background, tolerance and injury history. Otherwise, you’re often just running miles for miles.

More importantly, I believe the focus shouldn’t be on the total mileage you’re running, but rather the percentage of miles you’re running at race pace, easy pace, Vo2 max pace, etc. I think approaching mileage in this way helps prevent junk miles and helps keep the training marathon specific.

To illustrate, throughout the entire Pftizinger training plan, you’ll run 44 miles at marathon pace. This is a very small percentage of your overall mileage – depending on the specific mileage level you choose, only about 4%. While again, we don’t use “stock” mileage plans (it’s individualized) the number of miles at marathon pace three times (12%) that of Pftzinger.

Finally, as we’ve discussed a few times now in this comparison post, we focus on shorter, quality long runs that incorporate accumulated fatigue and marathon specificity whereas Pfitzinger follows the more traditional quantity and volume of long runs.

Since I have discussed this already above, I’ll simply link to those sections if you want a recap (or you skipped it).

Our individualized approach

Like many coaches, I am not a big believer in stock or template training plans. I strongly believe that there is too much individual consideration that needs to be taken into any training schedule.

Yes, I understand I am in the business of selling training and coaching, but I still believe a personalized plan is always going to be better than a stock plan – regardless of the training philosophy.

Specifically, mileage, number of training days and paces are critical elements of a training plan that are trivialized by template schedules. They simply assume that you’re running a certain number of miles or days per week based on your “experience level”.

However, beginner, intermediate and advanced designations for a runner can vary widely in mileage and tolerance for training. The only mileage progression and total that will work optimally for you is one that takes into account your background and injury history.

Likewise, factoring in your strengths and weaknesses is critical to maximizing the effectiveness of a training plan. By targeting your weaknesses and using your strengths to your advantage you can ensure that each and every workout is progressing you forward. As an example, a session of 200 meter repeats is somewhat wasted on the runner who has an abundance of natural speed while it’s essential to runners accustomed to marathon success.

Finally, getting your paces correct is essential for targeting the right energy systems. A lactate threshold run performed at 10-15 seconds faster than your actual threshold means you actually ran zero miles training your threshold and improving that system. It was a wasted workout. By getting your training paces correct you can maximize each session.

If you’re interested in receiving a customized training plan based on our training philosophy, you can start a free 14-day trial of our RunnersConnect membership. It’s a free opportunity to see what a customized, race-specific schedule can look like for you.