“Always Evolve” – one of my favourite valedictions used by esteemed physical therapist and blogger Mike Scott, DPT at the end of posts in his weekly series “Educainment.”

Running has certainly seen some evolution of thought over the last few years, much of it following the publication in May 2009 of Christopher McDougal’s best seller Born To Run, bringing with it bold claims that running barefoot (or wearing something as close as possible to barefoot while protecting you from environmental elements) can strengthen your feet, reduce running injuries, encourage proper running form, and improve performance.

Until then, the only experience many of us had of barefoot running was seeing the South African teenager Zola Budd on our television sets, running barefoot in the women’s 3000 meter race at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics.

Barefoot running

Whilst some runners have praised a transition to barefoot running (along with the typical shift to forefoot striking that barefoot running encourages) as a cure for an injury they were suffering, others have not been so fortunate and have seen it bring the onset of new injury, despite religiously following a slow, progressive transition period.

Clinical tests to date have also produced conflicting results. Barefoot running has been seen to reduce the risk of certain running related injuries, but increase the risk of others. It’s as if what works for some does not necessarily work for others. Sound familiar?

Regardless of personal experience, production of conclusive evidence for the benefits of barefoot running is still an ongoing project.

Minimalistic footwear

The increased profile and interest in barefoot running brought with it demand for less restrictive, less cushioned footwear, with the idea of allowing the foot to move and work in a more natural fashion whilst still providing a certain amount of protection.

As a result, today there is a wide spectrum of minimalistic footwear that, though not as extreme as barefoot style shoes like the Vibram FiveFingers, typically aim to provide less drop (difference between heel height and toe height), less cushioning, a wider toe box (more room for the toes) and more flexibility.

Like barefoot running, conclusive evidence for the benefits of minimalistic footwear is still a work in practice. A 2012 review in the Journal of Strength & Conditioning titled: “Running Barefoot or in Minimalist Shoes: Evidence or Conjecture?” concluded:

“Running barefoot or in minimalist footwear has become a popular trend. Whether this trend is supported by the evidence or conjecture has yet to be determined.”

Traditional footwear

Before any of you take “lack of conclusive evidence” as a reason to dismiss the possible benefits of barefoot running or minimalist shoes, I should point out – and this may come as a shock to you – that there is no evidence either that traditional running shoes can reduce injury or improve running performance.

Yes, you read that right. Though you were maybe told in the sports shop that your cushioned, stability or motion control trainer will help prevent injury, there is no evidence to support it. The problem is, the model that has been used for the last sixty years and more often than not is still used to help you select which trainers suit you is based on, well… not a lot.

Foot types

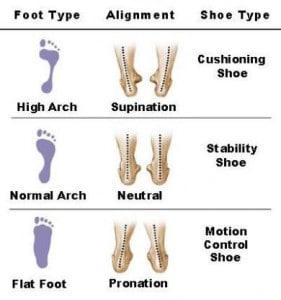

If you have ever been to a sports shop to buy a pair of running shoes (or have received an “ankle-down” gait analysis), chances are you are familiar with the diagram below, or something very similar. It links three “foot types” (based on the height of the medial arch) with three corresponding types of recommended running shoe:

The origin of the idea to group feet according to the height of the medial arch is not clear. Ian Griffiths, Director of Sports Podiatry Info Ltd suggests it may stem from a method of assessing footprints devised in 1947 by Colonel Harris and Major Beath as part of an Army foot survey. The first time an image associating medial arch height with shoe type actually appeared in print could have been the 1980 “The Running Shoe Book” by Peter R Cavanagh.

What we do know is that since 1980, running shoes all over the world have been recommended and sold using the Foot Type model. Selection typically follows an “assessment” (often involving the subject stepping onto a pressure pad or being filmed from the ankle down whilst running) of how much the medial arch drops (referred to in the diagram as “pronation”) or doesn’t drop (“supination”), along with the idea that somewhere in the middle (“neutral”) is normal, healthy and necessary for injury prevention (more on that later).

- If the arch of your supporting leg drops “too much”, you are labelled an “overpronator” and assigned a motion-control shoe that will in theory reduce the “overpronation”. If your arch does not drop “enough”, you are said to be an underpronator (or supinator), and assigned a flexible, cushioned shoe to absorb some of the shock that underpronator is said to cause.

- If you are somewhere in the middle, you are said to have normal pronation and are recommended a “neutral” shoe that in theory provides just the right amount of stability and cushioning. Leaving aside the question of who decides “how much” dropping is normal, it is important at this stage to remind ourselves that both pronation and supination are natural, integral parts of foot biomechanics.

Dr Shawn Allen, Diplomate of American Board of Chiropractic Orthopaedists explains:

“The foot is a biomechanical marvel. 26 bones and 31 joints, working together in concert to provide balance, stability, and locomotion. As we walk or run, the foot is supposed to go through a series of biomechanical changes, so that it can either adapt to the environment or become a rigid lever for propulsion. When these mechanisms fail, problems usually arise. When the heel hits the ground, the arch of the foot is supposed to partially collapse (pronation), so that the foot can adapt to the ground; in this position, it is flexible and “unlocked”. After the weight of the body passes over the foot, the arch is supposed to retract, and the foot becomes more rigid or “locked” (supination), so that you can use it to propel yourself forward. If the foot remains in pronation for too long, or does not supinate correctly, problems will develop over time.”

Problems with assigning shoes according to degree of pronation

So, the running shoe recommendation model is based on the idea that at midstance, just before the full weight of the body passes over the foot, the best position of the subtalar joint is “neutral”, i.e. the foot perpendicular to the horizontal ground.

The argument is that this “neutral” position signifies optimum functioning of the foot, optimum pronation and supination. One problem with this is the fact that the subtalar joint has variable anatomy. In other words, function will vary from person to person, so the ‘optimum’ position to be in will also vary. Ian Griffiths explains:

“Studies have shown that the structural anatomy of the human subtalar joint varies from person to person and it has also been shown that the location of the axis of the joint can and does vary from person to person; this will of course directly influence the magnitude of pronation and supination seen. In light of this sort of evidence it seems odd that there would be an expectation that all individuals could or should function similarly or identically.”

Taking the above into consideration, it should come as no surprise that there is no data or evidence that suggests “neutral” STJ alignment is linked with injury and/or pain free running. One study examined 120 healthy individuals both non weight-bearing and weight-bearing. Not one subject conformed to the criteria of “neutral” alignment.

Is there any evidence that “over-pronation” increases injury?

Almost all studies to date on “over-pronation” have found no evidence that it increases the risk of injury. A 2010 study concluded that the prescription of shoes with elevated cushioned heels and pronation control systems tailored to an individual’s foot type was not evidence based.

Another piece of research suggested the running shoe model was overly simplistic and potentially injurious. In fact, in this research, every ‘overpronated’ runner put into a motion control shoe during a 13 week half marathon training programme reported an injury.

Craig Payne, DipPod MPH, University lecturer and famed Running Research Junkie points out that lack of evidence for linking overpronation to injury may well be down to the methods used to measure pronation:

“The weakness of many of those studies is how they measured “pronation”; for example, some measure calcaneal eversion; some measure navicular drop; some do a footprint analysis; and some use a dynamic 3D kinematic analysis. The problem with that is that someone may be ‘overpronated’ on the measurement of one parameter and not ‘overpronated’ on another parameter.”

A study published this month by Teyhen DS. titled “Impact of Foot Type on Cost of Lower Extremity Injury” set out to determine the relationship between foot type and medical costs associated with lower extremity musculoskeletal injury, using a population of 668 healthy U.S. military healthcare beneficiaries in active military service for at least 18 months of the 31 month study.

It quantified level of pronation using the Foot Posture Index, a measurement of static foot posture that takes into account not one but multiple components that go into “overpronation”, devised by Dr Anthony Redmond, Arthritis Research Campaign Lecturer at the University of Leeds.

Whether static foot posture has much to do with foot posture whilst moving (e.g. running) is a discussion for another day. What the study did show is that of the 336 participants (out of the total 668) who sought medical care for lower extremity musculoskeletal injuries, a high percentage (no exact value available at this time) were those who had been listed as “extreme pronated feet” via the Foot Posture Index.

Future research will be needed to help see if degree of pronation via multiple component assessment (e.g. the Foot Posture Index) can be linked to injury. In the meantime, using just one component of “over-pronation” (e.g. medial arch height) to assign suitable footwear will continue to be a game of hit and miss.

Concluding considerations

- Is the whole running shoe recommendation model based on misconception?

- If it is, what model should be used, if any?

- There are certifications out there teaching shop staff how to sell running shoes. What are they based on?

- As a result of this debate, some are suggesting that runners should buy trainers based on “comfort” alone. Hard to imagine?

As I see it, just because an injury is present on someone with an “excessive” level of pronation (whatever that is…), it does necessarily mean that the level of pronation is the cause of the injury (correlation vs. causation).

It is imperative to consider and understand the biomechanics of the rest of the body (as well as foot posture) before reaching any conclusions. And even with all of that knowledge, it will still be a daunting task to be able to say “this is the running shoe you need!”

So, what should we base trainer recommendation on? A tricky question that we will consider next week. In the meantime, I am keen to know of your personal experience. What you are currently running in? What made you buy them? Have you managed to reduce injury via a change in footwear? Maybe a change in your footwear has led to an increase in injury? As always, I look forward to your comments!

Happy running!

Matt Phillips is a Running Injury Specialist & Video Gait Analyst at StrideUK & Studio57clinic. Follow Matt on Twitter: @sportinjurymatt

References

http://doctorallen.squarespace.com/what-is-pronation-and-supinati/

7 Responses

I run in Nike Lunarglide+ 4. By far the most comfortable shoes I have run and since buying them problems with my left knee have gone. However, I do have a recurrence of problems with my left achilles.

Having said that, in the period I have worn the shoes I have lost considerable weight which may have eased the pressure on my knee in any case, while the achilles issue occurred when I wore neutral shoes.

I’m beginning to get the impression that injuries are more about the volume of my running and the type of training I do (overdoing hills).

I agree with Gavin’s comment about volume of running and type of training having to do more with injuries than shoes do. I started running on a regular basis 2 years ago. The first year I got a bad case of plantar fasciitus in the fall after doing a lot of speedwork during the summer. Since then I have worked on getting a better base and have rotated shoes with different types of support (nuetral, stability, minimalist). My favorite are mild stability, but I feel that my feet and ankles do well by getting work with all the different effects and I haven’t had any problems for a year and a half. If a shoe doesn’t feel right, I just don’t use it as much (or at all). Listen to your body.

I work at a large running specialty store that does an “ankle down” gait analysis and have conducted many such analyses myself. Anyone in our stores nationwide has had extensive ongoing training to carefully judge what is typically enough over-pronation for a certain shoe category. It is taught that pronation is our body’s natural cushioning system, but how much is too much (typically)? I’ve seen elite (often female) marathoners with heavy over-pronation at the ankle, but the rest of their body is aligned properly so that other joints aren’t strained. However, this is rarely the case. Over-pronation at the ankle often causes adduction at the knees and hips and strains the joints. With the average runner, those that tell us they have knee or shin pain are often over-pronators currently running in a neutral shoe and need help from their shoe to align their legs and hips (at least until they are stronger and no longer need it).

Also, unlike what you implied in the article, we put very few people in a motion control shoe. In fact, I would say that from the analysis we conclude less than 1% need a motion control shoe. Most are recommended a stability, a few “neutrability,” and rigid foot types a neutral.

Furthermore, our shoe recommendation and judgement on over-pronation is based on what the shoe will do when you run in it. We always offer to re-record your gait before you buy the shoe. If you over-pronate too much for a certain shoe so that the shoe tilts onto the medial edge, the shoe will have a poor break-down pattern and increase your risk of injury. If the shoe stands straight up, the shoe will most likely break down more evenly and help to align the rest of your body.

Just want to know if anyone here know anything about saucony guide 5 running shoes I run my first marathon in this shoes my time was 4 hours 18?I have to buy new shoes for the comrades what shoes would you say be good for 89km race my feet is not flat on the ground when I put it done there is abit of a gap under my feet?

I’d also post this to the member forum, Tobias: http://discuss.runnersconnect.net/. You’ll get much better answers there

I get a 404 error on Jeff G’s link. Maybe that could be updated?

My experience: I’m still fairly new, but do like the minimalist approach. I did overtrain (too fast, too much) while wearing a traditional neutral shoe. In 2016, I switched to minimalist wear & slowed up a bit (to be exact: I gave alot more thought to the pace of each workout and didn’t continue to try to always run my fastest time for a given workout). Now, I have a slight irritation in my right Achilles, so I’m resting, doing strength training, and looking to fine-tune my stride. I’ve also been working on cadence (moving up from 82 to 88 strides per minute as measured with the same-side foot). I’m going to pay careful attention to my body and see if we can’t resolve this last “kink”

I have done some barefoot running (about 60 miles total since I began about 2 months ago). I like that as well, but my feet get dried out & I find the need to moisturize to prevent skin cracking (and have had to bandage up a couple of cracks when I didn’t do enough of that). Trails are nice for barefoot running. Asphalt is OK. Concrete seems fine. The latter two are only bad when they have gravel or pebbles on top. Then one gingerly steps over all of this.

That’s my two cents. Hope it helps. JH

Interesting article. As someone with low arches and 35 years of running/racing experience – and a range of injuries to go with it – it seems to me that women’s pronation pattern (or at least mine) differs somewhat. I land on the midfoot outside of my foot, but roll quickly in. My injuries tend to be tendinitis of the iliopsoas or around the knee. I once had metatarsal stress fracture, but (knock wood) no plantar fasciitis or notable Achilles tendinitis. My first official running injury, c. 1980, was iliotibial band syndrome, when I wore the Saucony Jazz. The sports medicine doc suggested arch supports. I’ve worn motion control and stability shoes, played around with orthotics. I’ve been in Mizunos for the last decade and seemed to have found a pretty good balance with the Wave Catalyst and my custom orthotic. I recently added the Wave Rider to rotate in training. However, I’m now facing a little of the old iliopsoas tendinitis… so there’s no perfect solution.