Last week we began to look at elements of running form common to most successful running styles by considering the issue of overstriding, i.e. where initial contact of the front foot happens too far out in front of the body, creating excessive braking forces on a generally locked out knee.

Runners who overstride take fewer steps per minute (also known as cadence) at a given speed than runners who do not overstride.

Research from the University of Wisconsin-Madison investigating the relationship of impact forces and cadence concluded that “subtle increases in step rate can substantially reduce the loading to the hip and knee joints during running and may prove beneficial in the prevention and treatment of common running-related injuries.”

From the research of famous running coach Jack Daniels at the 1984 Olympics, we now know that elite long distance runners at race speed almost always have a cadence of at least 180spm. We also see that the average recreational runner has a cadence of 150-170spm, with overstriders typically running with a cadence of less than 160spm.

Though overstriding is often accompanied by a heelstrike, it is important to remember that it is also sometimes seen with a midfoot or forefoot strike. Equally as relevant is the fact that although an initial contact closer to the body is commonly made with midfoot or forefoot strike, there are runners who manage it with a heelstrike (including Olympic silver medalist and New York City Marathon winner Meb Keflezighi).

The natural conclusion is that maybe less emphasis should be placed on worrying about what part of the foot touches the ground first and more on how close the front foot lands to underneath the hips.

Testing cadence

If we accept the evidence that a cadence of less than 160spm is associated with increased risk of injury and that the majority (if not all) of elite athletes have a cadence of at least 180spm, being aware of our cadence kind of makes sense.

If it is less than 160spm, an increase of 5-10% may well be an important factor in reducing injury. Even if it is over 160spm, increasing it by 5-10% may be a valuable tool (along with strength conditioning, dynamic flexibility, etc.) to help us move closer to the performance levels of elite athletes. As long as the changes are gradual and we listen to our bodies, it certainly seems worthwhile trying.

The Brighton Marathon Expo 2013

During the recent Brighton Marathon Expo 2013, I had the opportunity to test the cadence of over 50 long distance runners of all levels.

My aim was simply to introduce them and their non-competing colleagues to the concept of cadence, so the only instruments I used were a mini foot pod (clipped onto the shoe laces) that measured and sent speed, distance and cadence information to an iPad, and a Sprintex slat-belt treadmill (designed to mimic natural ground reaction forces better than conventional belt-driven treadmills).

As stated above, the purpose was not to produce a double blind randomized placebo controlled clinical trial (the list of design and conduct flaws is probably longer than the treadmill was). I did nevertheless make it clear to the runners that in order to give them helpful feedback it was vital they performed the test using their natural running form.

- Only a small percentage of the runners had any preconceptions of cadence, and results for anybody whose cadence seemed irregular and/or non sustainable have not been included in the data presented below.

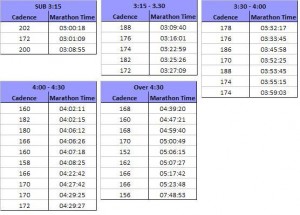

- Of the 53 runners I tested, 34 went on to finish the Brighton Marathon, giving me the opportunity to compare their cadence with their finishing time.

- All participants wore trainers and, following a brief warm up at their chosen comfortable pace (7km/hr – 10.5km/hr), had their cadence recorded during a 10 second run at their chosen race pace (9.5km/hr to 14km/hr).

What do the results tell us?

As far as a trial goes, yes, this test had more holes than Swiss cheese. However, it does seem clear from the results above that:

- As overall race time increases, cadence tends to decrease. The two participants with a cadence of over 190spm both managed sub 3:10 race times. I wonder what the 172spm runner with a time of 3:01:09 could achieve if he managed to increase his cadence by 10%?

- For runners who exhibited a high cadence but slow race time, maybe this is evidence that they need to focus more on other aspects of running fitness: strength, posture, mobility, etc.

I shall hopefully be working with a few of the runners in preparation for next year’s Brighton Marathon; it will be interesting to compare their race times alongside any increase in cadence.

I do wish I had also somehow recorded the level of injury that participants said they had suffered during training as there were multiple occasions where runners plagued with repeated injury showed a lower cadence than others who, though slower runners than their colleagues, had managed to get to race day injury free.

Food for thought

One runner who sticks out in my mind was a 59 year old grandmother who in just a year had come from never having run in her life to doing her first marathon. With no coaching whatsoever, her natural cadence at race pace was 170spm. She suffered no injuries in preparation for the marathon and happily completed it in a time of 5:00:49. Coincidence? Maybe. But definitely food for thought!

I hope this week’s article encourages you to explore your own cadence for different running speeds (a warm up pace will typically involve a slower cadence than a marathon race pace, just as the cadence used in a sprint will tend to be higher still).

If you’re interested in learning more about how to improve your own running form and develop the most efficient stride for YOUR biomechanics, signup for our 6-week online form course. The online course will help you run with proper form by teaching you the science of running biomechanics and provide you with a simple-to-follow, progressive set of exercises, drills and mental cues to help you make lasting changes to your form.

Depending on what you find, progressive increases in cadence (only 5% at a time) may be just the key you need to help take you out of an injury cycle or to a new personal best. For tips on how to measure your cadence and increase it gradually, see last week’s article. As always, do please let us know how you get on by leaving your comments below.

Happy running!

Matt Phillips is a Running Injury Specialist & Video Gait Analyst at

StrideUK

& Studio57clinic. Follow Matt on Twitter: @sportinjurymatt

References

1. Heiderscheit BC et al: Effects of step rate manipulation on joint mechanics during running. 2011 http://uwnmbl.engr.wisc.edu/pubs/acsm10.pdf

2. Daniels, J: Stride Rate When Running, 2012

http://blog.saucony.com/training/stride-rate-running/

4 Responses

Just curious about your statement above “For runners who exhibited a high cadence but slow race time, maybe this is evidence that they need to focus more on other aspects of running fitness: strength, posture, mobility, etc.”.

Any chance that this runner (these runners?) were shorter than average? The first thing that occurred to me was the possibility that shorter runners would automatically have a shorter stride and higher cadence.

Hi Cliff.

Yup, as with all things running, there are SO many variables to consider! Height / limb length would definitely be a factor. I’m 6’6″ and know for sure that running at marathon pace with a cadence of ~180spm is pretty unsustainable for me! While I look after a number of athletes 5’1″ – 5″4 who need to run at well above 180spm at their individual marathon paces – there is only so far their stride length can be increased… so instead their bodies choose to manipulate cadence.

Re: the statement Matt makes about running with high cadence yet slow marathon time. Again two many factors to go into without turning this response into an article in it’s own right! But… we’ve all seen the “shuffle runner” with a huge rate of cadence, yet very poor stride length (more a factor of technique this time than height per se). In my experience, these particular guys and girls can benefit greatly from increasing stride length (without over striding).

Hi Cliff, just looking through the archives and noticed I never replied to your comment! Apologies!

James is perfectly right, many other factors to running other than cadence, hence the “shuffle runner” with high cadence but poor stride length. Indeed maybe their high cadence is the product of not having a better alternative to get from A to B, unless of course they are consciously trying to maintain a high spm because of something they have read. Height can indeed be a factor too, although a look at the elites raises some interesting contradictions: Kenya’s Martin Mathathi is 1.67m tall and Sileshi Sihine of Ethiopia is 1.71m tall. And yet, both men have considerably smaller stride lengths than Kenenisa Bekele who is only 1.60m tall. The strategies used by these elites to run the same speed are not dependent on their height. More about that in the article I wrote here: Step Frequency vs. Step Length.

Thanks for the question!

Excellent article because it conveys valuable info and it is explained in terse and clear language. Comments were also helpful. Thanks! I am a triathlete (70-74 age-group) and I am sure that thanks to what you’ve explained in this and other articles, I will substantially improve my cadence which at the moment is rather embarrasingly low: I averaged 143 a couple of weeks ago.

Rafael Furlong (PhD. Litt.) MEXICO.