The iliopsoas is a large muscle that runs from your pelvis and lower back down to your femur.

As the primary “hip flexor,” it’s responsible for swinging your leg forward when you run, and because of this, it handles a lot of force.

It is named as such because the iliacus muscle merges with the psoas muscle, forming a single unit. The iliopsoas muscle also has a tendon, which runs along the second half of the muscle, from the femur to the bottom of the pelvis.

The iliopsoas plays a particularly important role when you run fast.

A 1986 study using electrodes to measure muscle activity found that increases in running speed cause surprisingly few changes in the activation patterns of most muscles, except for the hip flexors. These activate much more strongly when you increase speed, driving the leg through the air to help lengthen your stride.

Despite its role in generating speed, injuries to the iliopsoas are fairly rare.

A 2002 study on over 2,000 injured Canadian runners found that iliopsoas injuries didn’t even crack the top 20 most common running injuries; accounting for only 0.8% of all injuries.2

However, this isn’t very useful if you’ve already suffered an iliopsoas injury. You want to know what it is, how to fix it, and how to prevent it in the future.

That’s just what we’ll cover in this article.

Symptoms and diagnosis of an iliopsoas injury

An iliopsoas injury can involve the muscle, the tendon, or the fluid filled bursa next to it (or some combination of the three).

A 1985 paper in the British Medical Journal describes the classic symptoms of an iliopsoas injury: pain deep in the abdomen or upper groin area, tenderness when pushing on the muscle or tendon with your hands, and pain when you attempt to flex your hip against resistance.

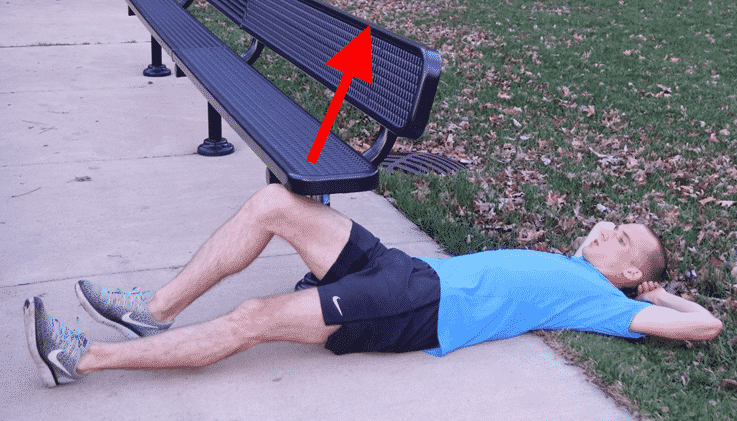

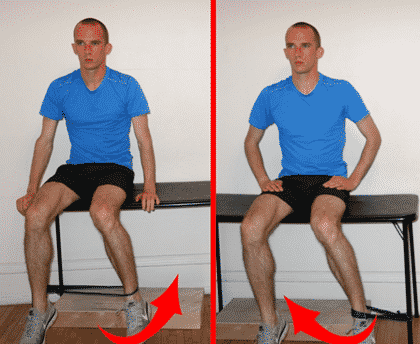

The authors in this study describe using manual pressure to resist hip flexion when testing for iliopsoas injury, but if you don’t have a friend or partner to help, you can replicate the test using a low bench or a bed frame. Bend your knee slightly and try to flex your hip against resistance and see if it provokes pain.

Of course, it will also hurt to run. Your hip flexor area may hurt during the stance phase of running or during the swing phase, and the pain will definitely get worse the faster you run.

The iliopsoas can also palpably and audibly “snap” when you run. This is termed “snapping hip syndrome,” though the connection between hip snapping and actual injury is tenuous.

One study on ballet dancers, for example, found that many people have an iliopsoas that snaps, but that does not cause any pain or functional limitations. Still, it appears that inflammation in the bursa adjacent to the iliopsoas tendon can cause the snapping and associated pain in some people.

Occasionally, iliopsoas injuries can be tricky to diagnose. There’s a lot of tissue in your hip, and all of it can get injured.

Osteitis pubis, an injury that involves inflammation of the pelvis, can sometimes cause similar pain to an iliopsoas injury, and femoral neck stress fractures are notorious for masquerading as hip flexor strains. If your hip flexor pain continues even at rest, or it does not improve rapidly with time off from running, you should see a doctor and get an MRI—this is the most reliable way to sort out what the real problem is.

Conservative treatments for iliopsoas injuries

Despite being a relatively rare injury among runners, the prevalence of iliopsoas injuries in other sports, like soccer, mean that there is more knowledge on effective treatment strategies than you might expect.

There are three main prongs to the standard treatment approach described in the medical literature. These are stretching, strengthening, and corticosteroid injections.

Stretching the iliopsoas and surrounding muscles

Stretching the muscles of the hip and thigh makes sense, as less muscular tension in these areas would reduce the stress on the iliopsoas.

There may also be some direct benefit to gently stretching the injured muscle and tendon.

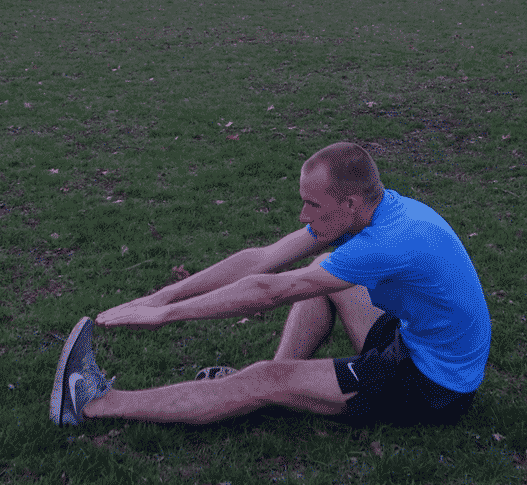

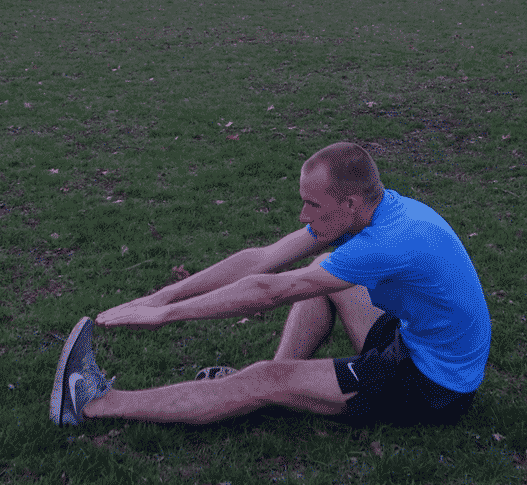

In a 1999 paper, a team of medical professionals in Canada describe a treatment program for iliopsoas injuries that includes stretching the hip flexors, piriformis, quadriceps, and hamstrings.

For best results, these muscles should all be stretched two to three times per day, for two 30-second sets each.

Strengthening the hip rotators

Strengthening exercises should focus on the internal and external hip rotators. The authors of the Canadian paper propose that hip instability, brought about by poor hip rotation strength, can cause excessive stress on the hip flexor area and injure the iliopsoas.

Their rehab program includes three stages. The first involves a basic internal and external rotation exercise that can be easily done with a table and an elastic resistance band. It should be done daily for three sets of 20 repetitions, on both sides, for two weeks.

After two weeks, you should add in three sets of 20 clamshell leg lifts, using a resistance band looped around your knees. Continue with this for two more weeks.

Finally, you can add in 3×20 mini-squats against a wall, using your hip external rotators to push your leg into the wall as you squat up and down.

Strengthening program summary:

| Weeks 1 & 2 | 3×20 sitting internal hip rotations with resistance band

3×20 sitting external hip rotations with resistance band |

| Weeks 3 & 4 | 3×20 sitting internal hip rotations with resistance band

3×20 sitting external hip rotations with resistance band 3×20 clamshell leg lifts with resistance band |

| Week 5 onward | 3×20 sitting internal hip rotations with resistance band

3×20 sitting external hip rotations with resistance band 3×20 clamshell leg lifts with resistance band 3×20 mini-squats with isometric wall press |

Corticosteroid injections

Another scientific paper describes successfully treating 40 professional soccer players with corticosteroid injections into the muscle (though avoiding the tendon, since direct tendon injections are associated with rupture). Doctors may guide the corticosteroid injection using ultrasound imaging.

Aggressive treatments for iliopsoas injuries

Though less proven, many runners have found soft tissue manipulation therapies, like Active Release Technique, to be useful. You can also do some rolling at home.

Because of its anatomy, the hip flexor area is especially difficult to access with a standard foam roller; you might find a well-inflated basketball or medicine ball to be more helpful.

Beyond this, the similarities between iliopsoas muscle and tendon injuries and other running injuries suggest that an injection of platelet rich plasma may be helpful, though this is definitely in experimental treatment territory—there aren’t even any case reports on using this therapy to treat iliopsoas injuries.

The area is likely too deep and too close to important biological tissue (i.e. your organs) for shockwave therapy to be useful.

A number of studies describe successfully treating iliopsoas injuries with surgery, though it should be thought of as a last resort, because the success rate of surgery is far from perfect.7

Return to running

As with other soft tissue injuries, scientific evidence suggests you can use a pain-mediated return to running program.

The details are as follows: first, give your hip flexor enough time to calm down. This may be a few days or weeks, depending on your age and the severity of your injury.

Once you start up running, you should of course build up gradually, but if you have mild pain or soreness, it’s not the end of the world. As long as it’s less than “5/10” on the pain scale, with 10 being your worst pain ever and 0 being no pain at all, you should be okay.

Additionally, pain should not persist the next day after you run, and your pain levels should be improving week to week.

Definitely avoid faster running for several weeks, and when you do reintroduce it, do so gradually.

If you are cross-training to maintain your fitness, be aware that the hip flexors are strongly activated when you aquajog, making it a poor choice.

Biking is likely the best choice, though you’ll have to experiment to see what your hip flexors will tolerate.

Conclusion

Iliopsoas injuries are not common, but if they do occur, you should treat them with stretching of the hamstrings, quadriceps, hip flexor, and piriformis, along with a progressive hip strengthening program.

If you don’t experience improvement, you should see a doctor, as you might have a different injury that is referring pain to your hip flexors.