After the long runs and hard workouts are over, and you are going crazy during the taper, what do we tend to do in the 10 days before racing the marathon?

Focus on race week nutrition, and obsess over the weather of course!

We wonder how each possible condition would affect our performance, but what if there was a way to find out what temperature would be best for you, then you could plan for a race in that climate.

Turns out we do have ideal racing temperatures, and they differ depending on your time goal.

In this article, we looked into the science behind this, and show you what temperature you are likely to finish highest in your race.

A while back, we took a look at the science behind how extremes in temperature can affect your running ability. The physiology behind this can be interesting and informative, but ultimately it only confirms what seasoned road runners already know:

Temperatures that are too hot or too cold spell trouble on race day.

Lab research is great for studying the biological effects of hot and cold temperatures on a runner, but it’s not quite as well-suited for answering the other big question about the weather:

“What’s the perfect temperature for a marathon race?”

To answer that, you need to do some serious number-crunching on a big set of data. Fortunately for us, a team of researchers in France and Lebanon were up for the task.

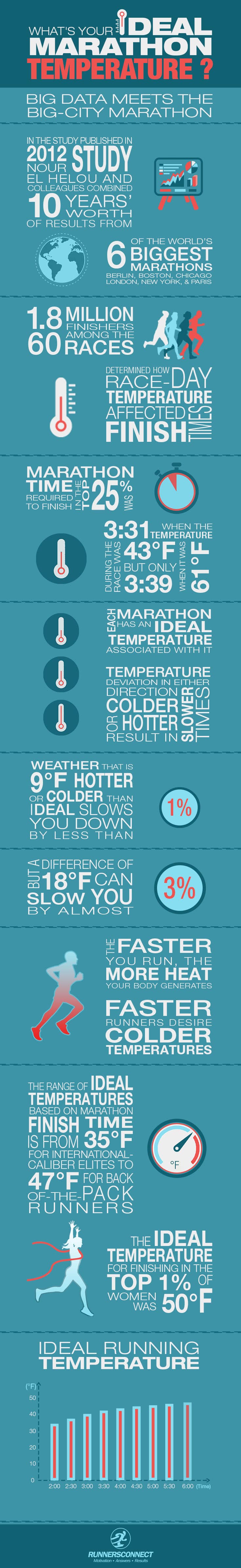

“Big data meets the big-city marathon”

In the study, published in 2012 study, Nour El Helou and colleagues combined ten years’ worth of results from six of the world’s biggest marathons: Berlin, Boston, Chicago, London, New York, and Paris.1 These totaled almost 1.8 million finishers among the sixty races. By combining the finish times from each of these races with historical weather data on the ambient temperature on the day of the race, El Helour et al. were able to determine how race-day temperature affected finish times.

Instead of looking at how specific runners responded to changes in temperature, like a laboratory study might do, El Helour et al. instead looked at how the time required to finish in a certain place in a race changed with different temperatures.

The marathon time required to finish in the top 25% at these major races was 3:31 when the temperature during the race was 43° F, but only 3:39 when it was 61° F.

After some number crunching and a lot of statistics, the researchers demonstrated that any particular marathon pace has an “ideal” temperature associated with it. Temperature deviations in either direction—hotter or colder—result in slower times.

The difference scales exponentially:

Weather that is 9° F hotter or colder than ideal slows you down by less than one percent.

But, this is crazy:

A difference of 18° F can slow you by almost three percent!

[bctt tweet=”This ideal racing temperature post is just what I needed to distract me during taper time! #runnersconnect”]

Faster runners need cooler temperatures?

The ideal temperature for a marathon also depends on how fast you are going to run:

Faster runners should desire colder temperatures. In retrospect, this makes sense, because the faster you run, the more heat your body generates.

Colder air temperatures facilitate removing this extra heat more effectively, as long as your body can maintain its own optimal internal temperature for running (i.e. as long as it’s not too cold).

The range of ideal temperatures based on marathon finish time for all runners is still a fairly narrow range, from about 35° F for international-caliber elites to 47° F for back-of-the-pack runners.

Look what we found:

By aggregating the relationship between fastest finish time and race-day temperature for the top 1%, top 25%, top 50%, and top 75% of both male and female runners across the sixty events, a surprisingly stable linear trend emerges, though there’s one snag—the ideal temperature for finishing in the top 1% of women (50° F) is a wild outlier, falling far outside the general trend for other finishers, among both men and women.

Barring a good explanation for this, we have to throw out this data point to continue our analysis. When we do this, we’re able to very reliably predict the ideal temperature for your marathon based on your predicted finish time.

You can check this out in the graph in our handy infographic:

[bctt tweet=”This info graphic on Ideal Marathon Racing Temperature is awesome! “]

But here’s the kicker:

Being up to nine degrees Fahrenheit colder or warmer than the ideal temperature shouldn’t slow you down by more than about two minutes (0.6-1.0 percent slowdown).

Temperature differences beyond this will have a bigger impact—a 2-3% slowdown for an 18° F difference, and over twice that much for differences of 24° F.

Other factors to consider

There are some shortcomings:

For one, the study was limited by the relatively weak (though plentiful) data it collected. It didn’t factor in the height or weight of the runners, which can affect heat and cold tolerance, and it didn’t take the course difficulty into account either.

Boston, for example, is a lot more challenging of a race than Berlin or Paris, which might affect how runners deal with heat and cold.

The curious outlier of the top 1% of female finishers is a puzzle, too—perhaps the elite women, who are by far the lightest runners in the field, do not deal with colder temperatures as well as slower women and all men do?

Or it could just be a spurious result.

Conclusion

In any case, these predictions should probably be tested in a laboratory to verify the statistical predictions. Now that doing the numbers on the “big data” has provided a useful set of results, it should be a lot easier to get a small group of three-hour marathoners together and examine how they respond to 45, 40, and 35° F temperatures, for instance.

Despite these limitations, the predictions from this study should come in handy. You can use the temperature guidelines to pick a race that’s usually held in ideal conditions, or you can check the forecast to see how much your pace might slow on race day if the temperature is far from the ideal range.

[bctt tweet=” I found my ideal racing temperature. You can too, click here:”]

3 Responses

What temperature, then, should you change your warmup plans from ‘warming up’ to ‘pre-cooling’? I’ve wondered this, as it seems that most warmup advice for marathons involves getting the core temperature up before the start a bit, but then pre-cooling seems to suggest the opposite on a hot race – get cold to hold off overheating…

I’m expecting temperatures to be in the upper 40s-50s before the start of my first marathon, then build into the mid-60s by the finish, potentially as high as 70. So would a good strategy be to de-layer and get uncomfortable before the start and try to maintain a slight chill as long as possible? Does shivering use up too much glycogen and negate the pre-cooling in that situation, or is it good to just embrace the pre-race cold for any race over X degrees?

Hi Jay, thanks for reaching out. You always want to make sure you are warming your body up, not just from a temperature point of view, but also just getting the muscles moving and working correctly. We actually wrote a post on how to warm up for a marathon, so you may want to check this out: https://runnersconnect.net/running-training-articles/how-to-warm-up-for-a-marathon/

You do not really ever want to allow your body to get into a chill state like you mentioned, you are actually better off taking an extra layer to the start line to dispose of just before you start the race. You should not ideally ever be in the state where you feel chilled. Take a read of our warm up article, and if you have any more questions, let us know 🙂

Given the odd result for elite women, the analysis of the top 25% runners achieving a certain time needs to be done separately for men and women., Otherwise it will be showing the effect on the majority of men who are the big majority of the top 25% finishers.