A few weeks ago I published a post with the data on the success rate of basic training plans.

I held off on publishing the data of our own custom training plans because I wanted the focus to be on the analysis of the basic plan data and not appear like a veiled sales message.

But, in this article I am going to provide the data on our custom plans and offer some analysis on why the data was so different.

Let’s dig in…

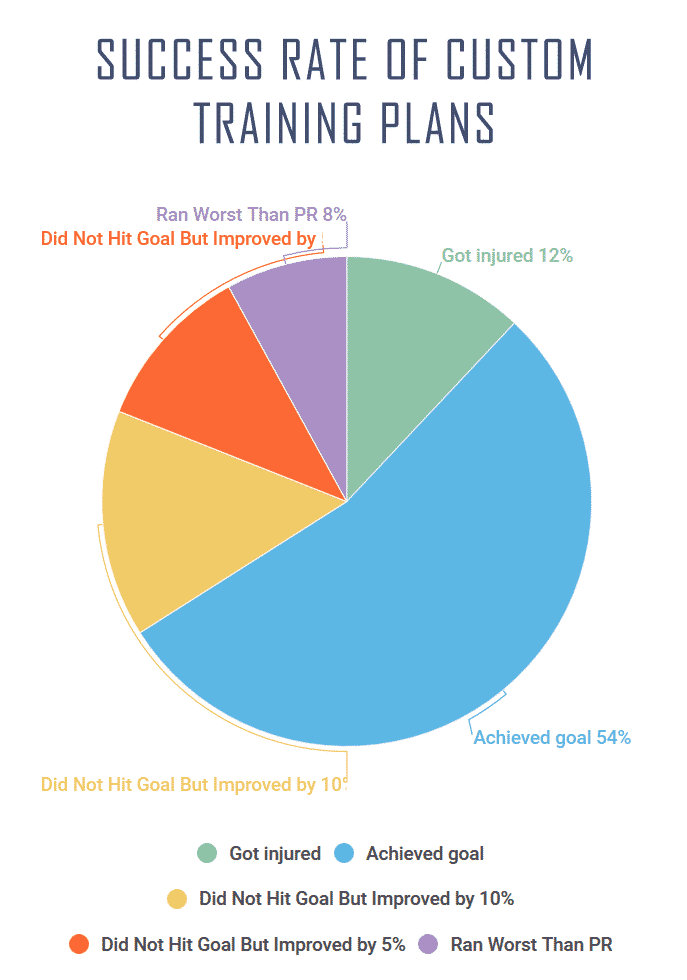

The Data on the Success Rate of Custom Training Plans

The data set for our custom plans covers the last 18 months and only includes goal races, not tune-ups or any race that was not marked as the “goal race” on an athlete’s plan.

I also tried my best to exclude as many repeat performers as possible, so this might skew the data somewhat. I took only the first result an athlete posted, even if they had multiple goal races in this time period.

The total number of athletes included in this data is 922. Here is the breakdown…

If you’re curious, we generally chronicle all race results each week. You can check them out here.

Analysis on Why Custom Plans Work Better

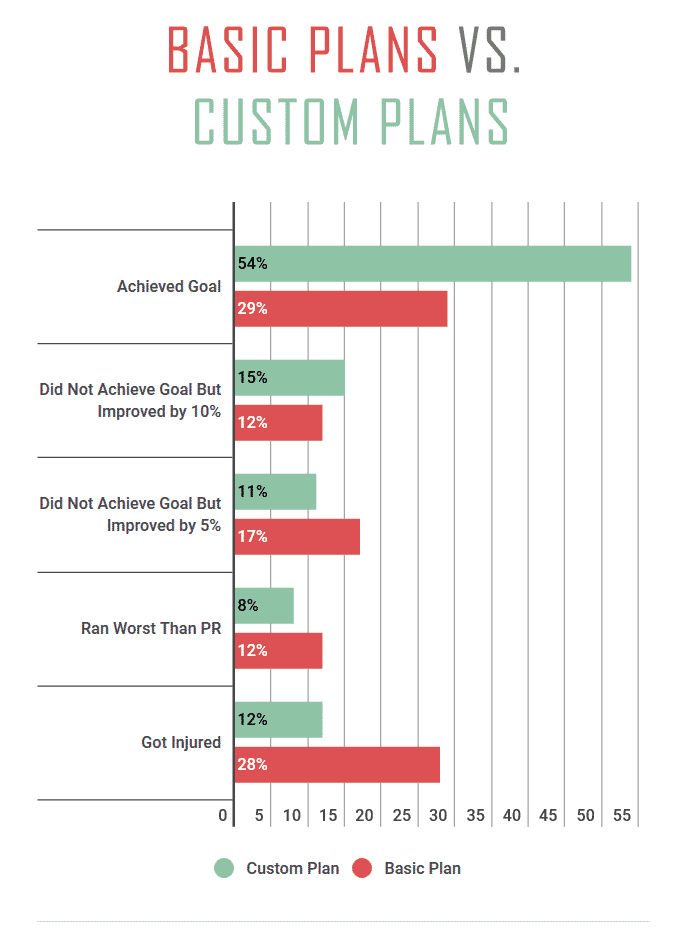

To compare the result to each “type” of basic plan, you can head back to my original post. But, here is the summary, with the basic plan data combined into one and averaged.

The two obvious differences are the injury rate and how many athletes achieved their goal. In both cases, a custom schedule clearly out performed a basic plan.

Here’s the three primary reasons I believe this happened.

Number of times schedule adjusted

One element we can track that I can’t track with basic plans (but I can assume it was zero), is how many times an athlete adjusted their training schedule.

Every time an athlete needed to adjust a schedule (this could be a missed workout, travel, sickness, minor injury, etc) we have a process by which a coach goes through and examines all the workouts and adjusts accordingly.

The cool thing about this is we keep the data on every single change to an athlete’s plan so we can reference later if we need.

On average, athletes adjusted their plan 4 times during their primary training cycle. 10% of runners had 0 adjustments and the most adjustments was 12 over a 24 week training cycle.

One thing I can certain of as a coach is that training rarely ever goes 100% according to plan. Sometimes, knowing how to adjust the plan is easy. Many times, it really isn’t.

All-too-often I see runners try to “make up” for a missed workout during the week without also adjusting the remainder of their workouts.

Even if you have extra rest or easy days, simply squeezing your missed workout back into your week isn’t a smart plan. The way I view training, each workout is designed to fit like a puzzle – to work on a specific physiological aspect and elicit a certain amount of fatigue.

When you squeeze a workout in, it throws off the balance of fatigue and recovery. This can dramatically increase the chance of injury and may result in too much accumulated fatigue, which means each subsequent workout is less effective.

Moreover, even when you have a good amount of data about a runner at the start of a training cycle, how they adapt to the training schedule is going to be unique.

Some runners will improve and respond to the training well and be ready for harder workouts sooner than others. Or, missing a larger chunk of training could mean the upcoming weeks of a plan no longer make sense.

So, when you have a basic plan that doesn’t adapt to how your body is responding then the plan is likely to be less and less effective as you make your way through each week of training.

Customized strength and rehab work

If you’re a long-time reader of RunnersConnect, then you know how adamant we are about including strength and injury prevention work in your training.

It’s not just dogma – the research has pretty much proven strength work can dramatically reduce your risk of running injuries.

Unfortunately, runners want to run and many, if it’s not explicitly prescribed to them, will usually skimp out at any given opportunity.

That’s why we build strength work directly into the training schedule.

But, even if you’re committed to strength training, we know that not all strength and injury prevention work is equal.

The type of strength work a marathoner needs to do vs. a 5k runner; or a beginner compared to a veteran; or even a younger runner vs. an older runner is quite different.

Plus, it’s important to take into account your individual injury issues. There’s less value in lower leg exercises when your injuries are always in your knees.

With a custom plan, you get the strength and injury prevention work tailored to your specific situation. This means you can include the routines most likely to improve performance and add the injury prevention work for the issues you’re most susceptible to.

Likewise, since the plan combines your running volume with strength volume, it’s less likely you go over board or compromise your running workouts with strength work.

I my opinion, this is a huge factor in the improved performance and reduced injury rate numbers of a custom plan.

Strengths vs. Weaknesses

Another piece of data I looked at was the length of training plan each runner used leading into their goal race.

On average, most runners had a custom training plan lasting 22 weeks. The longest was 6 months and the shortest was 4 weeks.

Typically speaking, most basic training plans are about 16 weeks long. Some might be 20 and the shortest I’ve seen are usually 12 weeks.

Obviously, there is an inherent advantage to having a longer amount of time to train. However, I think it’s also safe to assume that most runners using basic training plans are training before they start the schedule. So, I think this data point is still relevant.

In my opinion, the training directly before and the during the first few weeks of a basic plan suffer from inherent weaknesses.

First, with a custom plan, the training before your “race specific” segment begins is more targeted to your individual strengths and weaknesses.

Because we know what your weaknesses are, we can specifically work to improve them rather than train generically or focus on what you’re already strong at. I expound on this in more depth in this article on training between goal races.

Second, in the basic plans I’ve seen, the first few weeks are usually spent easing your body back into training. This means you spend less actual time training at your potential.

The authors of these basic plans are smart for easing runners into their plans. Since they don’t know exactly what level each runner is starting from, being conservative means less runners are likely to get injured by jumping in too fast, too soon.

It makes sense to sacrifice potential performance improvement to ensure most people that start your plan can’t get through the first few weeks.

By being able to target your weaknesses before race specific training begins and with the opportunity to take maximum advantage of every training week, a custom plan starts your training cycle ahead of the game.

Where things could be better

As a coach, it would be my dream to see 100% of the athletes we coach achieve their goals. My friends think I’m crazy when we’re out having fun and I suddenly stop and pull out my phone to jot down an idea I have about how we can improve our coaching process.

As you can see, we are not anywhere near 100% success rate.

Obviously, some of these issues are out of our hand; however, I do think we can continue to improve some parts of the training plan process.

More accurate assessment of goals

I think the most difficult aspect of being a coach, especially with athletes we’ve just started working with, is determining how realistic their goals are.

Sometimes, it’s obvious – like when you have a 2:05 half marathon PR and want to run a 3:45 marathon to qualify for Boston. But, sometimes it’s not so obvious. No coach wants to tell a runner they “can’t” do something.

We are currently working on ways to better correlate historical training data with potential improvement within a given time period.

I think this will help us better communicate to our new athletes what we think is realistic and what might be a stretch.

Relying on athlete feedback

Online, offline and in person – a coach can only be as good as the level of communication they have with an athlete and the data they receive.

We are still at the mercy of relying on athletes to initiate feedback and communication. If a runner won’t log their workouts or let us know how they’re training is going, then we can’t do a lot to help.

Of course, we’ve implemented ideas like check-ins for runners who don’t log their workouts. However, I’m not sure there is a specific solution to this problem, other than educating runners on the importance of communication and accurate logging.

It will be something we continue to work on and try and solve.

In summary

As I mentioned in my last article, I fully understand that our data is biased and wouldn’t hold up to any sort of scientific review.

However, I still think it was an interesting exercise to conduct. For me, it identified a lot of areas we could improve, helped us hone in on some of the aspects of our platform that contributed to success, and provided a very “big picture” view of the last 1.5 years for RunnersConnect.

It also made me re-think our approach to basic plans and eventually led to the decision of removing them as an option on our site.

Finally, I hope for you these two articles gave you some pretty concrete lessons to learn from.

If you do use a basic plan, analyze what I believe some of the weak points to be and adjust them so you don’t run into those issues. Likewise, implement some of the advantages of a custom plan into your schedule so you can try to make it work better for you.

Thanks for reading and let me know what your thoughts are in the comments section below.