Pain on the front of your shins after a run? Seems like a cut and dry case of shin splints (The Ultimate Guide To Shin Splints For Runners). But hang on, if that pain in your shin muscles, instead of the bone, it could be compartment syndrome.

Though rare, compartment syndrome can cause perplexing and long-standing pain in your shin, or more rarely, in your calves. Compartment syndrome is known more formally as chronic exertional compartment syndrome, which distinguishes it from acute compartment syndrome, which is a medical emergency that usually occurs after severe injuries or serious infections. In the case of this article, when we say “compartment syndrome,” we are referring specifically to chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg.

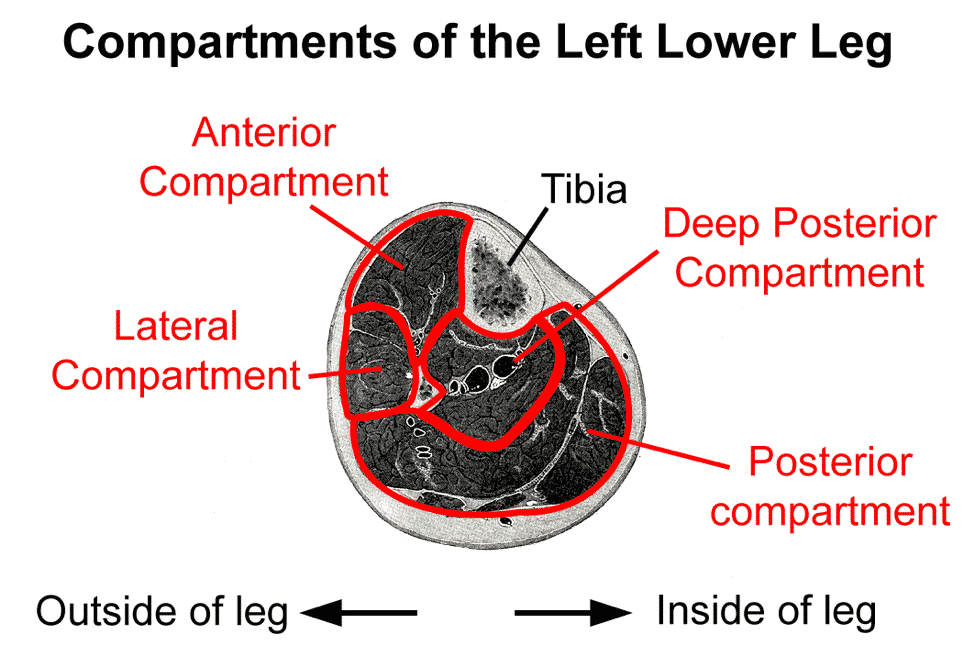

Compartments Of The Lower Leg

The muscles of your lower leg are divided up into four compartments. Each compartment is a sheath made of connective tissue. Your shin muscles, for example, are in the anterior compartment, while your calf muscles are in the posterior compartment.

Because muscles swell up during exercise, muscle compartments are typically large enough to accommodate this swelling. In the case of compartment syndrome, however, the sheath of connective tissue is too small, and when the muscles swell up when you run, pressure builds up inside the compartment and causes pain.

It’s possible to get chronic exertional compartment syndrome in any of the four compartments of the leg, but 95% of cases occur in the anterior or lateral compartments.1 This is good, since posterior and especially deep posterior compartment syndrome is more difficult to treat.

Risk Factors

Compartment syndrome is fairly rare, accounting for only 1.4% of all running injuries, according one study. For more on running injuries please read The Most Common Running Injuries in Men and Are Women More Prone To Running Injuries Than Men. So there is less data on risk factors than for more common issues like IT band syndrome.2 Here’s what we do know:

Compartment syndrome occurs more often in young runners. One study pegged the median age of developing symptoms at 20.1

Since the size of your muscular compartments is fixed by the time you’re done growing, it would make sense that problems would start to arise soon afterwards. Men and women seem to be at approximately equal risk.

Some researchers have proposed that rearfoot striking and overstriding are risk factors for anterior compartment syndrome, because the anterior compartment is loaded to a greater degree in rearfoot striking than in forefoot striking (the converse should be true with regards to the posterior compartment, but no scientific papers comment on this).

Symptoms

Because each of the four compartments of your lower leg can develop compartment syndrome, the specific location of symptoms is going to vary depending on which compartment is involved. As mentioned above, the vast majority of the time, your pain will be in the anterior or lateral compartments. These are on the front of your leg, on the meaty part of your shin. The posterior and deep posterior compartments are on the back of your leg, by your calves.

In any case, the hallmark symptoms of compartment syndrome are stiffness, tightness, aching, and pain in the affected muscle area that worsens when you run on it and diminishes quickly after you stop running (within half an hour or so). The onset of pain will often occur after a set distance or duration of running. In many cases, you’ll feel weakness when you try to dorsiflex or plantarflex your ankle (learn more by reading, Introduction to Running Biomechanics). There may also be burning, numbness, coldness, or tingling, and you may feel stiff, swollen lumps in your muscles when you run your fingers along the affected area.3

Some 60-80% of the time, compartment syndrome affects both legs at the same time.4 This is useful to know, since lower leg pain that’s present on both sides is more likely to be compartment syndrome, since most other injuries (with the exception of shin splints and occasionally tibial stress fractures) rarely occur on both legs concurrently.

Diagnosing compartment syndrome can be tricky because a number of other injuries can cause pain in the same area. Shin pain can also be caused by medial tibial stress syndrome (“shin splints”) or a stress fracture, but these cause pain on the shin bone, not deep in the shin muscles. An MRI or bone scan can rule out shin splints or a stress fracture in tricky cases. However, a muscle strain in the tibialis anterior or the calf muscles can mimic the pain associated with compartment syndrome.

Any injury to the lower leg that causes swelling, numbness, burning, or tingling should be looked at carefully, as these symptoms are not typical for other running injuries.

Because chronic exertional compartment syndrome is a lesser known injury, and because it can easily masquerade as a muscle or bone problem, it is notorious for taking a long time for doctors to diagnose. Many studies discuss patients whose symptoms had been present for several months before receiving an accurate diagnosis.5

Fortunately, there is a definitive medical test for compartment syndrome. A doctor will have you run on a treadmill until you start having pain, then stick a special needle into the various compartments of your legs. The needle is equipped with a pressure gauge, so it can measure your intramuscular compartment pressure directly. Because of this, it’s the gold standard for diagnosing compartment syndrome. Elevated pressures are a sure sign of compartment syndrome.

Treatment

Unfortunately, if you want to continue training at the same level as before your injury, there is only one well tested treatment for compartment syndrome in runners, surgery. The procedure, called a fasciotomy, involves making slits in the compartments of your lower leg to allow room for them to expand during exercise. Because compartment syndrome so often occurs on both sides, your doctor may elect to operate on the compartments in both legs, even if your symptoms are currently confined to only one side.

The success rate of the surgery depends on the location of compartment syndrome. Fasciotomy in the anterior compartment has a 60-80% success rate (measured by the proportion of patients who return to their previous level of exercise),6 while surgery for deep posterior compartment syndrome has only about a 50% success rate (though this was from an extremely small sample).7 In about ten percent of cases, compartment syndrome will recur a few months after surgery, typically because the compartments were not opened up enough. Followup surgeries are needed in these cases.

One fascinating pilot study published in 2012 describes an innovative nonsurgical approach to treating compartment syndrome: switching to a forefoot strike.8 Theoretically, this approach could work the greatest loads in the anterior shin muscles occur immediately following heelstrike, when the foot “slaps” down flat on the ground. But is forefoot striking enough of a change in loading to reduce or eliminate compartment syndrome?

The paper, authored by researchers at West Point, seems to suggest it may. In the study, ten runners with anterior compartment syndrome underwent a six-week transition to forefoot strike running. After switching to forefoot running, pressure in the anterior compartment after a run dropped by over half, and pain while running likewise fell significantly. Even at a one year followup, the runners were doing well and none needed surgery.

Though it’s very promising, this approach may not work for all cases of anterior compartment syndrome, and is definitely a bad idea if you have posterior or deep posterior compartment syndrome. That would only aggravate the problem, since forefoot striking would increase loads on those areas. Switching to a forefoot strike includes other drawbacks, such as an increased risk of metatarsal stress fracture, calf injury, and Achilles tendonitis. Still, it may be worth a try if you’d like to avoid going under the knife.

Cross Training While Injured and During Recovery

Cross training is recommended while you're injured and as you slowly return to running.

The best form of cross training for this injury is Aqua Jogging. Studies have shown that aqua jogging can enable a well-trained runner to maintain running fitness for up to 4-6 weeks.

Aqua jogging is a form of deep water running that closely mimics the actual running movement. Your feet don’t actually touch the bottom of the pool, so it is zero impact and safe for almost any type of injury. In my experience, the only time to avoid aqua jogging is when you have a hip flexor injury, which can be aggravated by the increased resistance of the water as you bring your leg up. Because aqua jogging closely mimics natural running form, it provides a neuromuscular workout that, in addition to aerobic benefits, helps keep the running specific muscles active. The same can’t be said for biking and swimming. The only downside to aqua jogging is that you need a pool that is deep enough to run in without touching the bottom. If you’re lucky enough to have access to a pool of this size, aqua jogging should be your first cross training choice.In one study, a group of ten runners trained exclusively with deep water running for four weeks and compared 5km race times pre deep water running and post deep water running.

The researchers found no statistical difference in 5k time or other markers for performance, such as submaximal oxygen consumption or lactate threshold.

In a second study, researchers measured the effects of aqua jogging over a six week period.

This time, 16 runners were separated into two groups – one who did aqua jogging workouts and the other who did over land running.

Using the same training intensities and durations, the researchers found no difference between the groups in maximal blood glucose, blood lactate, and body composition.

It get’s better:

Research has also demonstrated that aqua jogging can be used as a recovery tool to facilitate the repair of damaged muscles after hard workouts.

These findings make aqua jogging an important recovery tool in addition to being the best cross training method for injuries.

Need one more reason?

The calories burned aqua jogging are even higher than running on land, so if you want to avoid weight gain while you take time off from running, this is definitely the exercise for you!

Aqua Jogging Workouts For Runners

If you're interested in aqua jogging to rehab your injury, then the absolute best way is to use one of my favorite programs, Fluid Running.

First, it comes with an aqua jogging belt and waterpoof bluetooth headphones so you have everything you need to aqua jog effectively.

Second, they have an app that pairs with the headphones so you can get workouts, guided instructions on how to aqua jog properly, and motivation while you're actually pool running.

This has been an absolute game changer for me when I am injured.

I used to dread aqua jogging workouts because they were so boring and it took all my mental energy to stay consistent.

But, with workouts directly in my ear, it's changed the whole experience and I actually look forward to the workouts. So much so that I now use aqua jogging as a cross training activity in the summer, even when I am not injured.

Fluid running is an awesome deal when you consider it comes with the belt (highly recommended for better form), the waterproof headphones (game changer for making pool workouts fun), a tether (to add variety to the workouts you can do) and the guided workout app (to make your cross training structure and a whole lot more interesting).

That's why we've partnered with them to give you 2 additional running-specific workouts you can load into the app when you use the code RTTT .

Check out the product here and then on the checkout page, add the code RTTT in the coupon field and the workouts will be added to your order for free.

If you'd rather do the aqua jogging workouts on your own, here are some great ideas to get you started!

Medium Effort Workouts

The Pyramid

10 minutes easy warm up - 1:00 hard, 30 seconds easy - 1:30 hard, 30 seconds easy - 2:00 hard, 30 seconds easy - 2:30 hard, 30 seconds easy, go to 5:00 in 30 second intervals and then come back down the pyramid (4:30 hard, 30 easy, 4:00 hard, 30 easy etc). Finish with 10 minutes easy cool down.

Wave your hands in the air like you just don’t care

10 minutes easy warm up, 1 minute medium (87-92% of maximum heart rate or what feels like tempo effort), 1 minute sprint (95-100% of maximum heart rate or all out sprint), 30 seconds hands in air (keep moving your legs in the running motion, but put your hand above your head), 1 minute rest, Repeat 10-15 times. 10 minutes easy cool down.

Hard Workouts

One of the difficulties of cross training is replicating those truly lung-busting, difficult workouts.

So, if you’re going to be pool running quite a bit due to injury or limited training volume, invest in a bungee cord designed for sprinters.

Tie one end of the resistance band to a sturdy object (pole, lifeguard stand, pool ladder) and bring the other into the water with you.

Put the strap around your waist and begin aqua jog away from your starting point.

You’ll begin to notice the bungee tighten and resist against you (depending on the length of your pool, you may need to wrap the bungee around the supporting object or tie it in knots to make it shorter to feel resistance).

Spend a few moments testing yourself to see how far you can pull the bungee.

This is a great challenge and a fun way to compete with yourself during an otherwise boring cross training activity.

Now for the hard part:

Pick a point on the pool wall or side of the pool that you feel stretches the bungee to a very hard sprint that you could maintain for 60-90 seconds.

This will be your “sprint” marker that you’ll use on sprint intervals (95-100% of maximum heart rate or all out sprint).

Now:

Find a point that feels like the end of a hard tempo run.

Mark this spot as your “medium” interval distance.

When you complete the hard workouts, you can use these reference points to ensure that you maintain a very hard effort.

The springboard

10 minutes easy warm up, 90 seconds easy (slowly moving out and stretching the bungee), 2 minute medium, 1 minute sprint, 1 min rest (let the bungee pull you back – this is kind of fun). Repeat 10 times. 10 minutes easy cool down.

The race simulation

10 minutes easy warm up, 90 seconds easy (slowly moving out and stretching the bungee), 5 minutes medium (focus and concentrate, just like during the hard part of a race), 30 seconds sprint, 2 minutes rest. Repeat 4 times. 10 minutes easy col down

The lactic acid

10 minutes easy warm up, 90 seconds easy (slowly moving out and stretching the bungee), 2 minutes sprint, 90 seconds rest. Repeat 12 times, 10 minutes easy cool down.

I guarantee that with the bungee, you’ll get your heart rate through the roof.

You can challenge yourself and make aqua jogging more fun by seeing how long you can stay at your maximum stretched distance or seeing how far you can push it.

Likewise, if you have a friend who is injured (or someone willing to be a good sport) you can try pulling each other across the pool for some competitive fun.

Cross training can be tough, especially when you’re injured or want to be increasing your volume faster.

However, I hope that providing a variety of workouts, either through the Fluid Running app (which also makes it easier to keep track of the workout while in the water) or on your own can add a fun challenge in the pool and you can emerge from your injury with minimal fitness loss.

Return To Running

If there’s any good news about compartment syndrome, it’s that the recovery period after the surgery is fairly short.

You can start cross training in the pool or on the bike within one to two weeks of the operation (as soon as the incisions heal), and you can return to running after six to eight weeks.

The route for returning to running if you switch to forefoot striking is less certain. That’s going to vary based on how your body adapts to the change in loading on your lower legs, not to mention whether or not forefoot striking eliminates your compartment syndrome pain. As always, being gradual and cautious is the best approach.