In the previous few articles I’ve posted about my training as an elite runner, I’ve primarily exhibited specific training concepts within 2 week training blocks. So far, I’ve felt this to be a great way to demonstrate applicable workouts you could learn from without getting too lost in the complicated structure of a full training cycle.

However, in this article I am going to share the full outline my coach and I constructed in preparation for the Fall of 2007. My hope is that detailing an entire training cycle will help you see how workouts are designed to progress a runner from their starting point (whatever that may be) to an ultimate, peak fitness goal.

Background

In this specific training phase, our target goal was to work on speed and develop turnover after a marathon training cycle.

Because of this, the workouts were focused on speed development. Accordingly, the role of threshold runs and long runs was diminished in favor of shorter, but more intense workouts throughout the week.

You’ll notice that many of the workouts repeat themselves, sometimes multiple times. In this phase we used these workouts to assess progress as they were run roughly under the same conditions. The goal was to average slightly faster over the entire workout each session.

If you have any questions about the meaning of these workouts or abbreviations we used, just let me know in the comments section and I would be happy to answer.

The training

| Mileage | Workout #1 | Workout #2 | Long run | |||||

| 1-Oct | Rest | None | None | |||||

| 8-Oct | 40 mpw | None | None | 10-12 miles easy | ||||

| 15-Oct | 57 mpw | None | 5k tempo run | 14 miles easy | ||||

| 22-Oct | 75 mpw | 12 x 400m w/60 sec rest | 4 mile cutdown | 16 miles easy | ||||

| 29-Oct | 107 mpw | 5 x 1 mile w/3min rest | 5 mile cutdown | 18 miles easy | ||||

| 5-Nov | 110 mpw | 18 x 400 w/55 sec rest | 5k very hard tempo | 18 mile progression | ||||

| 12-Nov | 115 mpw | 12 x 800 w/2 min rest, hammer #7, #11 | 10k cutdown run | No long run | ||||

| 19-Nov | 115 mpw | 6 x 1 mile w/3min rest | 6 mile cutdown run | 18 mile progression | ||||

| 26-Nov | 100 mpw | 25 x 400 w/55 sec rest | 5 mile cutdown | 14 miles easy | ||||

| 3-Dec | 100 mpw | 3 x 1 mile w/3min rest | USA Club XC Championships | 13 miles easy | ||||

| 10-Dec | 115 mpw | 18 mile long run progression | 25 x 400, hammer #17, 21, 25 | 18 mile progression | ||||

| 17-Dec | 115 mpw | 40 x 200 w/30 sec rest | 6 mile cutdown run | 18 mile progression | ||||

| 24-Dec | 100 mpw | 12 x 400, hammer #9, #12, 60 sec rest | 18 mile long run – progression | Pre Race Workout | ||||

| 31-Dec | 100 mpw | 4 mile race NYC | 5 miles up tempo (marathon pace) | 8 x 800 w/2min rest | ||||

| 7-Jan | 100 mpw | 5 x 1 mile, hammer 2nd 800 on #4 | 3k Indoor race tune-up UK | 18 miles easy | ||||

| 14-Jan | 110 mpw | 25 x 400 w/55 sec rest | 2 x 3 miles at HM pace | No long run | ||||

| 21-Jan | 100 mpw | 7 x 1 mile w/3min rest | Boston University Indoor 5k | 18 miles easy | ||||

| 28-Jan | 100 mpw | 25 x 400 w/55 sec rest | 7 mile cutdown run | 18 miles easy | ||||

| 4-Feb | 100 mpw | 7 x 1 mile w/3min rest | 3 mile cutdown run | 12 mile long run | ||||

| 11-Feb | 90 mpw | Pre Race Workout | USA XC Championships | 13 mile long run | ||||

| 18-Feb | 90 mpw | Pre Race Workout | US Indoor National Championships | No long run |

What you can learn

As always, I share this training as an example that can provide valuable lessons you can apply to your own training or current running. I don’t suggest anyone should copy this outline verbatim, but hopefully seeing the different training concepts in action can inspire your workouts.

Changing energy systems

As mentioned above, this cycle of training was executed after an extensive marathon build-up. I had previously trained for two marathons in a row and the goal was to drastically change the training stimulus to ensure that I was hitting all the energy systems. Let me explain:

Training correctly for the marathon requires an intense focus on the on the specific demands of the marathon race. Very rarely in marathon training should you be doing VO2max, high anaerobic threshold runs, or pure speed workouts (notice I said rarely, not never). These are training adaptations that are important for success at shorter distances, but don’t translate well to good marathon racing.

Since my two previous training cycles had been marathon specific, I had intentionally neglected some of these energy systems for a few months. If I continued on the path of training the same physiological components I would have lost overall fitness and probably hit a rut in my training and racing. To continually improve, the body needs a change of stimulus – a new type of demand for the muscles and body.

This is why you’ll notice there are few true threshold runs and even the long runs are aggressive in nature. This specific block capitalized on my previous endurance work and attacked a new stimulus.

Keeping the volume high during the taper

You’ll notice that even during the taper portion of the training outline, the mileage stays relatively high (see the mileage column). The overall drop in volume is only about 10-15% of average weekly mileage.

Most of this mileage reduction is the result of a shorter long run and workouts that only total 4 miles, not the 6 or 7 they usually do. The easy, aerobic runs still remain roughly the same throughout the championship portion of the season.

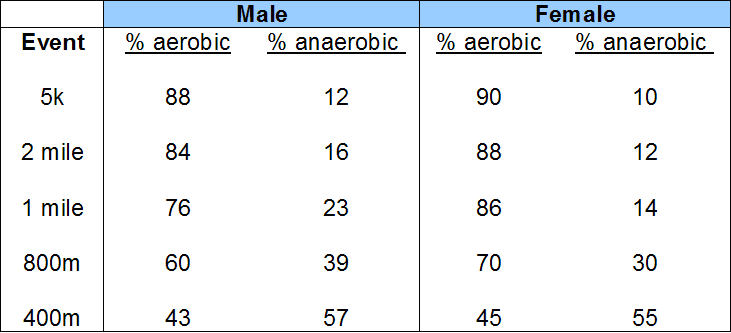

My strategy in regards to tapering is largely influenced by my coach at the time, Scott Simmons, who believes that significantly dropping volume the week of a race eliminates the energy system that contributes over 85% of the energy required for our specific race distance – easy aerobic runs.

For example, when we look the specific demands of long distance running, we clearly see a heavy reliance on aerobic respiration as a primary energy system:

Duffield, R., Dawson, B., & Goodman, C. (2005). Energy system contribution to 1500- and 3000-metre track running. Journal of Sports Sciences, 23(10), 993-1002

Duffield, R., Dawson, B., & Goodman, C. (2005). Energy system contribution to 1500- and 3000-metre track running. Journal of Sports Sciences, 23(10), 993-1002

Since the aerobic contribution to events longer than two miles is greater than 85 percent, significantly reducing the specific component of training that provides the most value to aerobic conditioning (easy runs) is flawed. To perform your best, you need to continue to train your aerobic system without producing fatigue.

But won’t you get tired if you don’t reduce volume?

By design, easy running is supposed to help you recover. An easy run increases blood flow to the muscles specific to running, helping to clear out waste products and deliver fresh oxygen and nutrients.

If you’re recovery runs during the hardest portion of your training cycle have enabled you to adequately recover between hard workouts, what would change the ten days before your race, when you’re not performing intense workouts?

Nothing changes. Significantly reducing your mileage does not result in faster recovery or more rested legs if your current volume has allowed you to recover properly during training. If it hasn’t, this speaks to a larger problem about your current training program.

I hope you’ve enjoyed another installment of a look inside the training of an elite runner. Please don’t hesitate to let me know what you think – did you find this type of post more helpful than a two week block?

Next week, we will be detailing the training of Nate Jenkins, a 2:14 marathoner and 7th place finisher at the 2008 Olympic Trials Marathon. Stay tuned!