Linking running form to injury is always a tricky area when it comes to research.

The moment one study links a certain movement pattern to a particular running injury, another study will come along and conclude there is no link at all. Such contradictions serve to strengthen the argument that although we all run, our individual physical and psychological makeup means that our bodies can react differently to the associated strains that running brings.

It therefore often falls on coaches and therapists to use successful experiences they have with one runner as a potential way to help another, whilst avoiding the temptation of labeling any one strategy as the ‘magic bullet’ that will help everybody.

A good example of this is a strategy that frequently helps some runners (not all!) get over ‘ITB Syndrome’, the common pain on the outside of the knee where the Iliotibial Band (ITB) inserts on the lateral condyle of the tibia.

This strategy? Correction of the ‘Cross-Over Gait’.

What is cross-over gait?

Imagine you are running down a line in the middle of a road.

If when landing your foot/feet cross over this middle line, you are said to possess a cross-over gait, in other words a very narrow running gait.

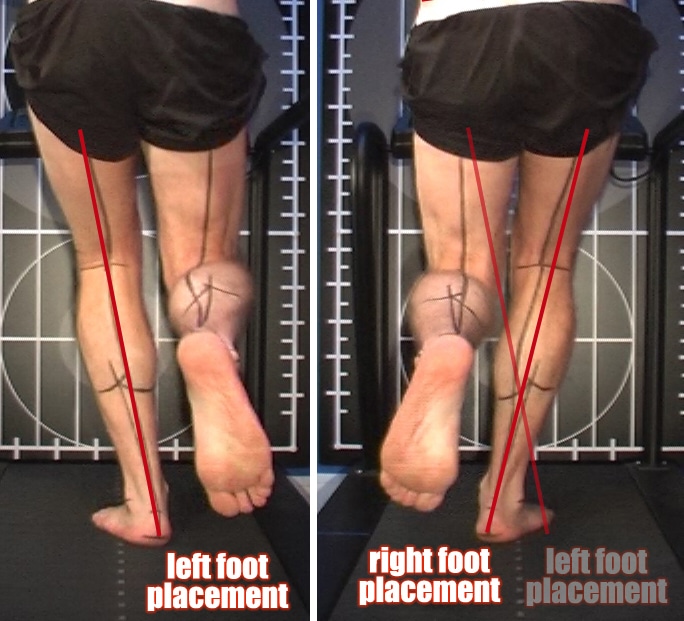

An example can be seen in the diagram below where the midline is on a treadmill. For each foot placement, both the left and right foot can be seen to cross the midline.

It is important at this stage to note that not all runners who experience ITB pain run with a cross-over gait. Likewise, not all runners with a cross-over gait suffer from ITB pain.

However, clinical experience does show that runners who are suffering from ITB pain and possess a cross-over gait can benefit from following a suitable ‘gate-widening’ program. In many cases, the pain is reduced if not eliminated.

Not always, no magic bullets, but enough to make it worth trying.

What does the research say?

A study by Meardon et al. (2012) titled ‘Step Width Alters Iliotibial Band Strain During Running’ assessed the effect of step width during running on factors related to ITB syndrome. Fifteen recreational runners ran at various step widths including their preferred width, +5% of their leg length and -5%.

- Measuring changes in strain and strain rate according to step width revealed that greater ITB strain and strain rate were found in the narrower step width condition.

- Relatively small decreases in step width substantially increased ITB strain as well as strain rates. Running with the feet just 3cm wider reduced ITB tension by up to 20%.

The study concluded: ‘increasing step width during running, especially in persons whose running style is characterized by a narrow step width, may be beneficial in the treatment and prevention of running-related ITB syndrome.’

What causes cross-over gait?

This is where most articles would present you with a tidy table showing you which muscles you need to ‘strengthen’ and which muscles you need to ‘stretch’.

Hip weakness is indeed linked to many running injuries, although the exact mechanisms of injury remain unclear. The gluteus maximus and gluteus medius are in particular regarded as key players in controlling the degree of hip adduction (leg moving inwards towards midline) and internal rotation, with poor control of these thought to lead to increased stress on joints, ligaments, and tendons.

Though a program of ‘strengthening’ certain muscles and ‘stretching’ others can lead to the targeted muscles becomes stronger or more mobile, experience and research shows that there is not always a sequential ‘carry over’ to when you are running.

Those of you who have religiously followed a stretching & strengthening programme only to find the pain is still there are testament to this.

The thing is, although anatomy books present muscles to us as individual units with origins, insertions and functions, real life movement depends on global organisation of the body as a whole. The roles of muscles can change drastically according to where the joints they work across are in relation to each other, time and space. Also, overlooking and controlling all of this movement is the brain.

Running is a cyclical motion, as we saw in this article . Every part of the gait cycle is a product of what came before.

How your right leg moves whilst it is off the ground (the ‘swing’ phase) will directly effect how it later moves when in contact with the ground (the ‘stance’ phase). Likewise, how your right leg moves during the stance phase will have a direct effect on how the left leg moves during its swing phase, and so on.

So, although a cross-over gait is indeed typically accompanied by a drawing in of the leg in late swing phase, just stretching the muscles on the inside of the leg (adductors) and strengthening the muscles on the outside of the leg (abductors, e.g. gluteus medius) may not automatically stop this drawing in from occurring when you are out running.

In the same way, the excessive pelvic drop we often see on the opposite side’s supporting leg during a cross over gait will not decrease just because we integrate some hip hikes into our conditioning program.

Don’t get me wrong, I am not saying give up on these hip strengthening and mobility exercises.

I am just saying that in order for the brain to select a new way of moving (and stop feeling threatened by the overload that our current way of moving is causing), we need to practice the new movement within its true context – in other words, we need to practice it whilst running. This is the essence of gait-retraining (considered in more detail here).

Gait retraining whilst on the run

Gait-retraining has many forms and ideally involves you making a modification whilst receiving some form of external feedback, e.g. from a coach or a mirror.

However, in the case of slightly widening your stride, this can be achieved very simply whilst you are out running.

Find a line (e.g. one that marks a bicycle lane) and as you run down it notice if your foot / feet are indeed crossing over it on each landing. If so, take 20 seconds to widen your stride just enough so your feet do not cross the line.

Note that this drill is to be performed over just 20 seconds a time, not for the whole run!

We need to be careful not to overload muscles not used to this new movement pattern so always start with short intervals. Specific moments within your easy long run would be an ideal opportunity to practice this.

How long does gait retraining take?

As we saw in the article ‘Introduction To Running Biomechanics,’ for a change of habit to become permanent it is generally agreed that the process of change needs to pass through four stages – a structured journey that sees conscious effort evolve into unconscious competence:

- Unconscious incompetence. You have not had the gait analysis yet and are therefore totally unaware (unconscious) of the movement pattern we plan to modify.

- Conscious incompetence. You have had the gait analysis and are now conscious of the new movement pattern and can commence a suitable program of strength & conditioning / drills / gait retraining.

- Conscious competence. You are now able to produce the desired movement pattern but occasionally still have to think about it when running, i.e. it is not yet happening completely naturally.

- Unconscious competence. Congratulations! You are have producing the new movement pattern whilst running without consciously having to think about it.

Efficient distance running demands optimum use of all available energy so the ultimate goal is for the brain to be able to select the right movements at the right time without the need for any conscious effort, for as long as possible.

Gait-retraining needs to involve a slow, progressive return to running.

In re-distributing the forces associated with running, we have to be careful that the newly receiving muscles do not get too much too soon. They need to be given time to adapt to the new demands.

This is where the strengthening and stretching exercises that are typically done can help as they will aid the muscle’s tolerance to these new demands.

Don’t always Run in a straight line

Though the exact reason for many running injuries is still unknown, most will agree that the repetitive nature of running plays a great part.

To ensure that the same tissues are not receiving the same overload every run, we encourage variety – rotate different types of footwear, vary the type of ground surface you run on, etc. With this in mind, something else I advise people suffering from ITB syndrome is try not to always run in a straight line. Mix it up, thread to the left and right like a meandering river.

Maybe not during a race (unless you are in pain in which case I do recommend you try it) and definitely not on a treadmill, but when outside training think variety.

If injury comes from repeated overloading of a tissue, reducing the demands on that tissue and increasing the demands on others by changing direction makes sense.

Modified lunges

Regular readers will know I am a big fan of coach Jay Johnson’s version of Gary Gray’s ‘Lunge Matrix’, as I demonstrate here. All exercises can be modified to suit what one is trying to achieve, and lunges are no exception.

In my experience, of the many runners I have seen with a cross over gait, the majority (if not all of them) perform a forward lunge with a similar cross over. They also tend to naturally allow the front knee to shoot way over the toe, in effect using the quadriceps muscles of the thigh to stabilize on the way out and push on the way back (instead of engaging the glutes as we need to in running).

Consciously performing a wider lunge introduces the brain to alternative movement, typically accompanied by a sudden loss of balance.

I commonly use the visualization cue of ‘lunging on a railway line instead of a tightrope’. Keeping the knees in line with the feet as you lower the back knee towards the ground again introduces new movement, instead of allowing the natural adduction of the leg that we saw during the cross over running gait.

These and other teaching points can be seen in this video.

In conclusion

If you suffer from ITB syndrome and run with a cross-over gait, a slight widening to your step width may reduce / eliminate ITB pain.

Isolated exercises to strengthen/stretch typically targeted muscles may not be enough to promote a natural widening of your gait (though they may well play a crucial part in you being able to maintain the wider gait and delay onset of fatigue).

As well as performing the exercises, embark on program of gait-retraining in which you consciously add the new movement pattern whilst out running (for short bursts, not for the whole run). In theory, over time this conscious effort to coordinate new movement will become an unconscious pattern, leading hopefully to an elimination of the pain!

If you have any experiences in battling ITB syndrome by employing any of the recommendations above, do please let us know by leaving a comment below. We look forward to hearing from you.

RunnersConnect Insider Bonus

Download our free Top 5 IT Band Prevention Exercises guide.

It’s a PDF with the 5 best exercises to help you prevent IT band syndrome.

5 Responses

Part of my overcoming of ITBS has been to slow down alot for 60% of weekly distance, 6:30min/km or slower than 10min/mile. Ive noticed that its very difficult to run with excessive crossover when running that slow and in a couple of weeks ive noticed a change for less crossover in my faster paces as well.

Thanks for posting this! I never understood how strengthening my hips could help with ITBS until I realized that I have a cross-over gait as well. This post has saved me!

I’m confused by this article. I’ve seen similar on other websites such as “thegaitguys,” critical of a crossover gait, and on a crusade to elimimate this evil that’s infecting running, etc. My confusion, possibly, comes from a slight lack of clarity in these presentations. There are a number of websites, books, and elite marathon and ultra marathon runners that advocate “fox running” or “in line running”. They are pretty clear about NOT “crossing over” the center line, but rather maintaining a level pelvis (front to back and side to side), while rotating the hips forward with the leg to better maintain the body over it’s center of gravity, while avoiding side to side movement trying to balance the body over two separate tracks or lines, to either side of the center. Is there really a conflict here? Or is there a lack of clear communication on a difference between running down a single line, which some say is the most natural style of running used by children, and “crossing over” that single line? In your other materials you emphasize that running is a game of inches, that’s it’s the little things that make a champion. Please help clarify for me. I’m not doning “in line running” yet, but I’ve been studying it, and watching my 15 month old grandson run as he matures, but he’s not old enough yet to see what happens yet.

In the recent popular book “Unbroken” about Louis Zamperini, who died recently at age 97, the author notes on page 17 “Louie had a rare bio-mechanical advantage, hips that rolled as he ran; when one leg reached forward, the corresponding hip swung forward with it, giving Louie and exceptionally efficient, seven-foot stride. After watching him from the Torrance High fence, cheerleader Toots Bowersox needed only one word to describe him: “Smoooooth.”

I’m a 67 year old, widowed, retired grandpa whose trying to get back into running again starting at age 62, after giving it up almost completely since age 20 due to a college injury. I’ve read about a dozen books on barefoot and minimalist running, and I’ve been very cautiously nibbling at it. I go barefoot around the house, and on easy walks, but only run maybe every other day and usually only 1 to 3 or 4 miles barefoot on in very minimalist zero drop shoes. My goal is not competitive, but to just be able to run and not damage myself. There is certainly a lot of debate about how to do that. My podiatrist says that the whole barefoot / minimalist thing is a fad, and he’ll be happy to make orthotics for me and get me into motion control shoes, etc.

I do have “Morton’s Foot” with the ball of my second toe longer than the ball of my big toe. I have had some difficulty getting enough weight over on to the balls of my big toes and not too much on the balls of the second toes, where I can get calluses if I’m not careful. I’ve tried hard to learn and use techniques to do this, without reverting to pads and orthotics, and after 5 years I think I’m just starting to get it. Finding good advice on this specific problem has been difficult.

I used to have knee pain and pain behind my left heel (bone spur there), but they have both gone away completely for 5 years doing what I’m doing. Now it’s mostly the struggle spreading weight over the balls of my feet and not getting too much on the balls of the second toe.

Also curious what the percentage of the GENERAL U.S. population is with longer second toes (not just Morton’s Foot) but anyone with longer second toes. The answers are all over the map, from 5% to more than 50%. And I’ve heard that 80% of foot problems that send people to podiatrists, etc. seem to come from people with longer second toes.

how to change and widen your stride as a soccer player with it band issues. second time, suffered from right it band (surgery) two years ago.

Peter, if you follow the suggestions in this post, it should help. You need to be careful not to over-stride though, then you will reduce your inefficiency, and put yourself at a greater risk of injury. Sounds like you have been through enough! This may help you also https://runnersconnect.net/running-injury-prevention/it-band-injury-runners-stretches-exercies-treatments/