When diving into the science of running performance, the concept of VO2max is almost unavoidable.

Defined simply, VO2max is the maximum rate that your body can extract oxygen from the air.

When you run, that oxygen gets absorbed in your lungs into your bloodstream, gets pumped by the heart, and travels to your muscles, where it’s put to use burning fat or carbs.

Everyone agrees about that part.

The controversy begins when you start to ask the obvious next questions:

- How does VO2max contribute to performance

- And what part of the oxygen delivery system—bloodstream, heart, or muscles—matters most when it comes to determining your VO2max?

So, that’s what we’re going to examine in today’s article by digging into the research.

VO2max measures metabolic power, not running speed

When runners talk about performance, we mean something very specific: speed!

If you get an invitation to watch a “high-performance 5k,” you’d justifiably be expecting to see some fast times.

But VO2max doesn’t measure speed—it just estimates your body’s metabolic power output.

More specifically, it’s an estimate of your highest aerobic power: when you’re running fast enough to hit VO2max, virtually all of the oxygen you’re consuming is being used to burn carbs for energy.

Being able to generate lots of aerobic energy is great, but it doesn’t guarantee that you’ll be able to run fast.

To go from aerobic power output to running fast requires converting that metabolic power into forward motion—that’s where running economy comes in.

Much like a car with a powerful engine but flat tires, a high VO2max is not very useful if it’s paired with poor running economy.

For longer events, like the 10k and half marathon, there’s an additional factor at play: your highest sustainable level of oxygen consumption.

Normally, if you try to run at, say 90% or 95% of your VO2max, your oxygen consumption won’t be stable—it’ll quickly climb to 100% of your VO2max, and you’ll soon become too tired to continue.

At a lower value, say 70 or 80% of your VO2max, you’ll be able to maintain a stable rate of oxygen consumption over time, and you’ll last much longer before getting fatigued.

That value—the highest percentage of VO2max you can maintain at a steady-state—is your steady-state max.

Just like runners can have different VO2max values, they can also have different values for this steady-state max—even if they have the same VO2max!

To run fast, you need all three factors:

- The ability to produce a lot of aerobic energy (VO2max)

- Do so in a sustainable way (steady-state max)

- And efficiently convert that energy into forward motion (running economy).

VO2max and performance in runners

Since VO2max is only one of three major factors influencing running performance, it shouldn’t be surprising that VO2max on its own is not a particularly good differentiator of running ability among runners who are already pretty fit.

One study on nearly 200 top-level Spanish runners found that VO2max on its own could not identify the best elite distance runners compared to their merely pretty good counterparts.

Additionally, Nike’s Breaking2 Project, which did comprehensive physiology testing on some of the best marathoners in the world, found high, but not amazingly high VO2max values among these elite marathoners.

Many of them clocked in at 65–70 mL/kg/min, even though elite 5k runners can often hit 80 mL/kg/min or higher.

In larger and more diverse samples, though, there’s no denying that there’s a link between VO2max and performance.

A 2021 study of military recruits in Norway whose 3k race pace ranged from nearly 12:00/mi to 6:00/mi found that VO2max alone explained two-thirds of the variation in performance across the recruits.

Clearly, a high VO2max is the price of admission for high-level performances—but doesn’t guarantee fast times on its own.

Central or peripheral? Blood and heart versus muscles

The other big controversy with VO2max is what biological factors determine its value.

In principle, any link in the oxygen delivery chain (blood, heart, or muscles) could be the bottleneck.

Another way of thinking about this question is whether you’re limited by oxygen absorption by your blood, or oxygen utilization by your muscles.

Most physiologists agree that the biggest factor in determining VO2max is simply how many red blood cells you have.

More red blood cells means more hemoglobin, and more hemoglobin means you can carry more oxygen in your blood.

As pointed out in a 2016 commentary article by physiologists Carsten Lundby, David Montero, and Michael Joyner, total hemoglobin alone explains nearly half of the variation in VO2max across athletes.

If you incorporate cardiac output—the maximum amount of blood your heart can pump per minute—that fraction leaps to over 90%.

Things only get heated when considering whether blood volume and cardiac output are the only factors that matter.

Some physiologists believe the above evidence is convincing, while others argue that a couch potato with an elite athlete’s heart and bloodstream would not have the necessary oxygen-extraction capabilities in their muscles to make full use of the extra oxygen.

VO2max in practice: increasing blood volume and cardiac output

Regardless of the controversy, one thing is clear: if your VO2max is limiting your performance, boosting your blood volume and increasing your cardiac output are the most promising strategies.

As for how to go about boosting these two factors, the research is less controversial: both blood volume and cardiac output can be improved with interval workouts that hit at least 90% VO2max.

In practice, that means coming within about 8–10% of your maximum heart rate (or hitting >90% of heart rate reserve, if you want a more precise metric).

For specific workouts, see the section below on different workouts you can use for various race distances.

For optimal cardiac output benefits, these intervals should be supported by high overall training volume: padding out your weekly training with plenty of easy to moderate runs, to the extent that your training schedule allows.

Specific VO2 max Workouts you can Implement

Now on to everyone’s favorite: the training details!

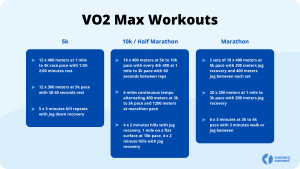

VO2 max for the 5k

Out of the most common race distances, VO2 max is most important in the 5k.

While the first portion of 5k training will focus on building aerobic endurance, think of this phase as building the foundation of a house.

The last 1/3rd of a 5k training plan, however, will emphasize VO2 max workouts – think of this as the roof.

A few excellent examples of 5k specific VO2 max workouts are:

-

12 x 400 meters at 1 mile to 3k race pace w/1:30-2:00 minutes rest

-

12 x 300 meters at 5k pace w/ 30-40 seconds rest

-

5 x 3 minutes hill repeats with jog down recovery

Looking for more information and workouts for training for a 5k?

Check out our 5k Specific Training post. Or, how about our Base Training for 5k and 10k post?

VO2 max for the 10k and half marathon

The specific demands of the 10k and half marathon aren’t heavily reliant on VO2 max, but it is still an important component to round out fitness.

In the 10k and half marathon, you should have a VO2 max workout scheduled every 2-3 weeks to keep the system in check and support other energy systems (aerobic development and threshold training).

My favorite workouts to blend into 10k training are:

- 16 x 400 meters at 5k – 10k pace with every 4th 400 at 1 mile-3k pace w/ 60 seconds between reps

- 4 miles continuous tempo alternating 400m at 3k-5k pace and 1200 meters at Marathon pace

- 4 x 2 minutes Hills w/ jog down recovery, 1 mile on a flat surface at 10k pace, 4 x 2 minute Hills w/ jog down recovery

We have a great article on Specific Training for the 10k here, and a 6 week 10k specific training plan for applying the adaptation principle.

VO2 max for the Marathon

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on how much you like lung-busting interval workouts), VO2max is not a big component of marathon training.

However, It is still useful and important to include some VO2 max workouts and speed work in your training plan every 3-4 weeks to help your form and efficiency.

My marathon go-to’s are as follows:

-

2 sets of 10 x 400 meters at 5k pace w/ 200 meters jog rest and 400 meters jog between each set

-

20 x 200 meters at Mile to 3km pace w/ 200 meters jog recovery

-

6 x 3 minutes at 3k to 5k pace w/ 3 minutes walk or jog between

Recap

VO2max measures the highest rate at which your body can extract oxygen from the air—and since oxygen is used to burn fuel for energy, it’s essentially a measure of your aerobic power output.

Not surprisingly, VO2max is a huge contributor to running performance—but not the only contributor.

To run fast, you need a high VO2max, the ability to sustain a high percentage of your VO2max at a steady-state, and the ability to efficiently convert metabolic power into forward motion.

VO2max depends heavily on your heart and bloodstream: most of the differences in VO2max across different runners are attributable to the total amount of hemoglobin in your blood, and the maximum rate your heart can pump blood.

So-called “peripheral” factors, like how well your muscles can extract and use oxygen, only contribute a little to VO2max, if at all.

These peripheral factors do matter for performance, but probably via their influence on whether you can sustain a metabolic steady-state at a given rate of oxygen consumption.

Understanding the origins of VO2max—and its limitations as a measure of performance—can help focus your training.

If VO2max is holding you back, the best way to improve it is by focusing on workouts that target blood volume and cardiac output: interval workouts with repeats that bring you within about 8–10% of your maximum heart rate.