Last week, I had the pleasure of working with NHS Choices, the United Kingdom’s biggest health website, as part of their “Couch to 5K” plan designed to help get people off the couch and running either 5K or 30 minutes by the end of 9 weeks. Given that many of the people I work with are seasoned runners, the experience served as an important reminder of the significant challenges that can face a novice runner.

Whatever one’s motive is to start running, be it to reduce the risk of chronic illnesses such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes or stroke, to boost one’s energy levels or help with weight control, taking that first step can be an extremely daunting prospect.

In addition to the fear of getting injured through not knowing how or where to start, one of the most powerful barriers to deal with is often heightened self-awareness and fear of ridicule.

Fortunately, novice runners soon learn that despite their initial concerns not only is the incidence of complete strangers pointing and laughing at them extremely low but also most people seem to have a natural ingrained respect for the solitary runner and, on seeing them, start self-reflecting on how they themselves should be making more of an effort to look after their own health.

Indeed, one of the deep attractions and admirable traits of running is that it’s just you and the road, no equipment, no obvious skill requirement, no judging…

So what happens when we add a handful of rather ridiculous looking running drills to the equation? Panic.

What is a running drill?

Courtesy of Runningtechniquecoach.com

Unless you have ever trained at a running track, the chances are you are not familiar with seeing runners perform movements like that in the photo above.

The photo is from an excellent article by running coach Brian Martin aptly titled “Why silly walking leads to better running” and provides an example of the variety of “running drills” designed to help develop important components of running technique. If you have not yet seen the video chat between Brian Martin and coach Mark Gorski, I thoroughly recommend you do.

Though for obvious reasons drills like the one in the photo take runners very much out of their comfort zone, they can serve as important facilitators for improvements to running form.

Is running more not enough to improve running form?

Courtesy of www.russgillespie.co.uk

Given that most of us were happily running around all day when we were children, there is logic to the argument that “running is natural – put in enough miles and you will naturally get better at it.”

Yes, running in itself is simple; the success of start-up projects like “Couch To 5k” are testimony to this and it is this same simplicity that encourages us to start pushing ourselves and testing our limits. We start increasing the frequency of our runs, the intensity, the duration and before long we are no longer like children in a park, stopping when tired or thirsty. This is where skill comes in, where sustained effort can rely on possession of a more efficient running form.

Though there is no one-size-fits-all way to run, the mechanical process of running can be hindered by individual biomechanical constraints. The repetitive nature of running (1400 to 1900 steps a mile) means that as individuals all of us seem to have personal limits as to how far, how fast and how often we can run before injury sets in.

Identifying and reducing our individual constraints and improving our running efficiency allows us to set ourselves new limits.

Should beginners do running drills?

As always, appropriacy of any exercise or drill must take into account an individual’s needs and goals. With regards to helping people getting from couch to 5k, we have seen one of the main barriers can be lack of confidence and fear of ridicule so any suggestion that success will rely on performing ridiculous looking marches and skips should best be avoided!

However, as soon as confidence has been established and passion for self improvement sets in, I believe the introduction of running drills, if only once a week, can reinforce what I feel to be the most fundamental and yet underappreciated concepts behind running performance:

Injury prevention for runners comes down to either running less or strengthening the body. Which one you choose is up to you.

Running drills help “drill home” the near fact that if you are constantly raising the demands on your body through running, unless you add suitable weekly conditioning exercises to your training program you will eventually reach your limits and most likely get injured.

Examples of running drills

Below are four drills that I have selected to exemplify the value of running drills within your training programme. The screenshots are from fellow running resource website RunnersFeed.com, with direct video links to their YouTube feed, which provide clear, concise instructions, teaching points and demonstrations.

You will be able to find plenty more examples of drills elsewhere online (Brian Martin offers a good selection at runningtechniquecoach.com) but as coach Brandon Laan stresses, it is vital to perfect the basic drills before progressing to the more advanced.

The drills are designed to imitate specific characteristics of efficient running form, e.g. upright posture, head position, arm movement, hip extension, knee drive, etc. but as you will soon appreciate correct execution also depends on, and therefore develops, coordination and dynamic balance.

Trying to skip before you can march will not help you advance quicker. Nor will embarking on the B’s before you have mastered the A’s. Slow, deliberate progression is needed in order to pass from conscious incompetence to conscious competence and then onto unconscious competence. Only then will your body be able to unconsciously select the new improved movement patterns when you are out running.

The A-March

The A-March emphasizes a driving knee lift, upright posture and coordinated arm swing. Though it is the most basic form of running drill it must not be rushed. Building sufficient confidence when performing the march will help extremely when the time comes to perform the far more flamboyant skip version.

Overcoming embarrassment is paramount. Start slowly but exaggerate confidence – hold the body upright and stable, move the legs and arms with deliberation (as Brandon says “place one hand in your back pocket and scratch your nose with the other), encourage a wide range of motion at the hips, knees and ankles. Do not worry about speed, it will come in time as you develop balance and coordination.

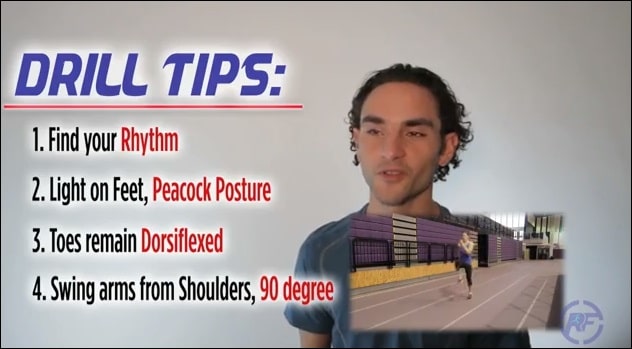

The A-Skip

Skipping is far more challenging than marching as it requires a higher degree of co-ordination and therefore neural activity. It also places more load on the musculoskeletal system, leading to increases in strength in the supporting leg.

Correct execution will rely on having first achieved the ability to do a fast march, as the frequency of foot strike (cadence) in skipping is twice as high. There is also noticeably more temptation to allow the arms and legs to cross the midline of the body, something that needs to be discouraged as excess rotation is thought to reduce running efficiency.

As with marching, move confidently with a “Peacock Posture,” as Brandon says in the video. Lose your inhibitions. Again, try not to get hung up on speed – it will improve naturally as your coordination develops.

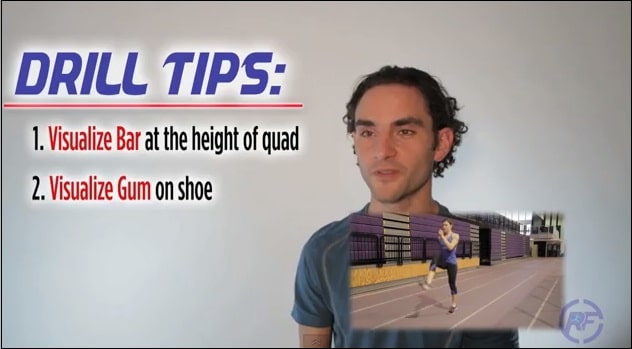

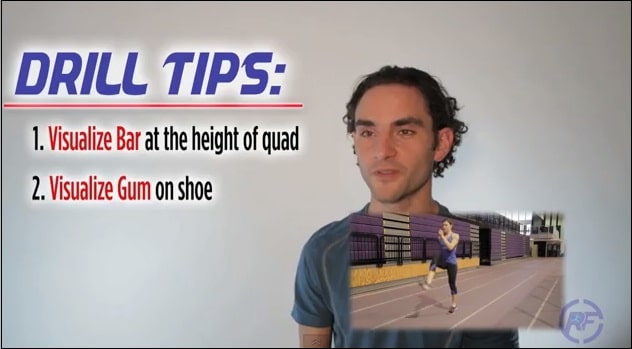

The B-March

In adding straightening of the knee to the raised leg of the the A-March, the B-March emphasizes hamstring flexibility and body control, and provides the basis for learning more advanced drills. It is vital you do not to progress to it until you have mastered the A-March.

As Brandon emphasizes in the video, visualization is key so imagining yourself “clearing the bar” and “striking the ground like you are trying to get gum off your shoe” are both great cues. It is the strike to the ground that generates the forward propulsion, something that carries over directly to propulsion in running.

The B-Skip

As with the marches, the B-Skip is an extension of the A-Skip, with the lower leg “clearing the bar”. Importance should be given to “pulling down” the leg in order to strike the ground as this is thought to determine the power of the hip extension as the body moves over the supporting leg.

Once the above three drills have been mastered, the B-Skip can be a very useful specific tool in developing strength and coordination of the gluteal and hamstring muscles, something that as we have considered in previous articles can directly affect running performance.

In conclusion

Running drills can be an excellent way to learn and develop efficient movement patterns that your body will then be able to adopt when running.

Weekly running drills can strengthen specific muscle groups needed for running, especially the muscles of the feet, calves, shins, thighs and hips. They also help prepare the ankle, knee and hip joints for the specific range of movements required during running.

If you’re interested in learning more about how to improve your own running form and develop the most efficient stride for YOUR biomechanics, signup for our 6-week online form course. The online course will help you run with proper form by teaching you the science of running biomechanics and provide you with a simple-to-follow, progressive set of exercises, drills and mental cues to help you make lasting changes to your form.

If you have had any good or bad experiences from use of running drills, we would as always love to hear about them in the comments section below!

Happy running!

Matt Phillips is a Running Injury Specialist & Video Gait Analyst at StrideUK & Studio57clinic. Follow Matt on Twitter: @sportinjurymatt

References

1. Martin, B.: Why silly walking leads to better running. (2012)

http://www.runningtechniquetips.com/2012/12/running-technique-drills-video-feature/

2. Runnersfeed.com: Running Drills (2011)

http://runnersfeed.com/category/training/running-drills-training/page/2/

3. Mac, B.: Technique Drills for Runners (1998)

http://www.brianmac.co.uk/tecdrill.htm

2 Responses

But, but !! Doesn’t this — “So, even if you are aware of a biomechanical constraint that may be reducing your running performance, trying to modify it whilst running is not the answer.” — contradict the studies you describe by Dr. Davis on your “Gait Retraining” page, in which she instructed the runner on the treadmill simply with a verbal instruction to run with her legs more apart and her patella aligned forward, and after 8 weeks the plantar fascitis went away and her new, improved hip rotation was being maintained? Doesn’t it seem misguided to expect instantaneous improved economy with conscious technique changes? To me it is un-surprising that the economy will initially be less as the brain tries to figure out how to assimilate this new way of doing things and make it natural again. It seems like Dr. Davis’ studies, with both subjects getting sore in the exact spots that got needed to be strengthened simply by using conscious technique changes during runs, gets both the 2 “conscious vs. strengthen” birds with one stone: if you know what to consciously target, with time, it works. Of course, that’s a big “if,” and the need for constant mirror-ing I guess is impractical.

When I said “whilst running” I was referring to the bulk of everyday running. Though gait retraining is an ever expanding field of research, I feel it is still important to distinguish the periods of conscious correction that it involves from the miles that need to do be run without any conscious effort. Research continues to show that any conscious attempt to correct form results in reduced efficiency. I hope that helps!