As part of the constantly evolving study of how best to rehabilitate specific running injuries, research shows us that conscious modification of certain movement patterns linked to specific injuries whilst running can lead to lasting changes in running form, elimination of pain (whether correlation or causation is still up for debate) and non recurrence of the specific injury. Where strength training alone has been shown to not automatically lead to changes in running form, ‘Gait Retraining’ has had better results.

Irene Davis, Ph.D., is director of the Spaulding National Running Center at Harvard University, Massachusetts. For those of you who are regular visitors to RunnersConnect, you may well be familiar with the name as Dr. Davis has been a leading researcher in the running field for more than 20 years, with a particular focus on demonstrating that runners can change their running form.

Gait retraining is a method she has developed of changing movement patterns via real-time feedback. And yes, it’s all done whilst the subject is running.

Movement patterns related to injury

Much of Davis’ research has been about identifying movement patterns related to injury (as opposed to performance enhancement), particularly tibial stress fractures and anterior knee pain (two of the most common injuries that runners sustain). Given that females are at least twice as likely to sustain these injuries, subjects used in Davis’ research are generally women.

Data already collected has linked stress fractures with comparatively high peak tibial shock and increased vertical loading rates. It has also linked anterior knee pain with increased hip adduction and internal rotation. It is these movement patterns that Davis used in her development of Gait Retraining.

Walking vs. running

August 1996, Vol. 20, No. 2

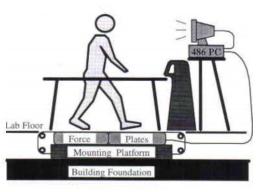

As Davis was aware, numerous studies had already successfully shown how using a form of real time feedback training could alter gait whilst walking. In 1996, Dingwell et al. used an instrumented treadmill with force plates and visual feedback to improve the gait of a group of unilateral, trans-tibial amputees.

In 2005, White et al. had similar success in helping patients who had undergone a hip replacement achieve a more symmetric gait via visual feedback from an instrumented treadmill. However, studies involving feedback during running were sparse. Davis and her team set to work. Two of her five preliminary studies are described below.

Study1: Gait-retraining a runner with plantar fasciitis

Subject: 40-year-old female runner; plantar fasciitis in right foot

Situation: Pain prevents continued running

History: Had been running average of 15-20 miles per week. Use of foot orthotic devices had proved unsuccessful.

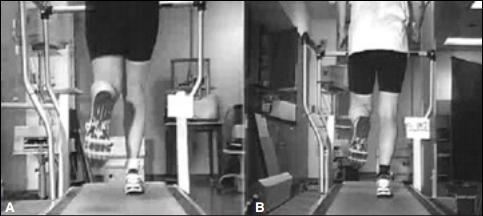

Visual analysis of the patient’s running allowed Davis to identify right hip in excessive internal rotation (see photo above) and knee valgus (angled inwards) throughout the support phase. A high degree of midfoot pronation was also observed. Manual muscle tests went on to reveal weakness of the right hip abductors and external rotators, and excessive hip internal rotation range of motion.

An instrumented gait analysis was used to quantify these gait deviations. It was hypothesized that “the plantar fasciitis this runner was experiencing was related to the internally rotated hip and medially deviated position of the knee, placing greater stress on the arch of the foot.”

The treatment

Length of training program: 8 weeks

Source of Visual Feedback: Full-length mirror in front of treadmill

Method: The treatment consisted of the patient being verbally instructed as follows: “Keep your knees apart” and “keep your patella pointed forward”.

The length of run was gradually progressed from 10 minutes up to 32 minutes by the end of the 8-week session. Frequency was gradually reduced from three times a week to once a week for the last two weeks. The mirror and verbal feedback were progressively removed.

The subject reported soreness in the external rotators and abductors of the right hip but this resolved within two weeks. She also reported a progressive reduction in the effort required to maintain the aligned posture.

Results:

At the end of the 8 week gait re-training program, there was a significant reduction in hip internal rotation, hip adduction, and knee abduction (see photo comparison below).

At a 6-month follow-up, the subject was running 30 minutes, 3 to 4 times per week without pain. The analysis revealed that hip external rotation and abduction were still being maintained, but the knee was returning to pre-training state.

Conclusions:

The results concluded that the patterns of running gait could be modified and maintained over 6 months. They also suggested that that the modifications had led to a resolution of the patient’s symptoms. The subject did report that the symptoms would return when she became fatigued and reverted to her old running pattern but this in itself further supported the hypothesis that it was the “abnormal” mechanics that were causing the symptoms.

Study 2: Gait-retraining a runner with patellofemmoral pain

Subject: 46-year-old female runner with pain in the front of the left knee.

Situation: Recently training for a marathon but developing pain prompted her to seek advice.

History: Had been running for 15 years, averaging 15 miles per week.

A visual gait analysis of the subject revealed increased left hip adduction and internal rotation, knee valgus (see photo above) and excessive rearfoot pronation during stance. Manual muscle testing showed weakness of the left hip abductors and external rotators.

On performing a lateral stepdown, the subject exhibited excessive knee valgus, hip adduction, and femoral internal rotation. It was hypothesized that this runner’s patellofemoral pain was “due to an excessively internally rotated femur and would be resolved if her gait mechanics could be altered so that she exhibited greater hip external rotation during stance.”

The treatment

Length of training program: 10 weeks (2 visits a week)

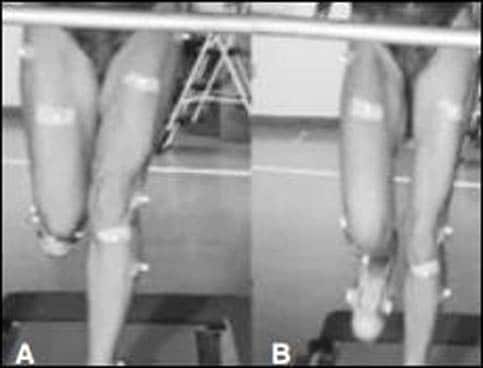

Source of Visual Feedback: Retroreflective markers placed on left leg.

Method: The subject ran on a treadmill for 30 minutes. A 6 camera motion analysis system allowed the subject to observe on a monitor real time marker position data during left stance position. The subject was asked to alter her gait mechanics by shifting the chosen angular curve in the appropriate direction to provide the “desired” alignment. In other words, the subject was asked to reduce her hip internal rotation (without altering her foot placement angle).

Results:

Over the 10-week training period, the runner was able to reduce her amount of hip internal rotation as she ran. Muscle soreness was experienced in her hip abductors and external rotators following training but only for the first two weeks. By the 5th week of training, the visual feedback was periodically withdrawn. The patellofemoral pain had gone and she was able to reduce the amount of hip internal rotation throughout stance (see comparison photo below).

Significance of gait retraining

The above two studies, along with others, demonstrate that gait patterns can be changed. Dr. Davis points out that there is still much work to be done in this area. More research is needed to determine the optimal gait retraining protocols for the most effective results. More follow up studies are required to test the permanence of gait related changes and their influence on future injury incidence.

With so many factors potentially contributing to running injuries, some would argue that it is impossible to prevent them, unless of course you limit yourself to what you know you can handle and stay within those boundaries. But how many runners are prepared to do that?

The frustration of seeing others around you managing to run further, faster, and for longer whilst you know that any attempt by you to increase distance, speed or duration will lead to injury can be torture! Doing less is rarely an acceptable option, so if biomechanical movement patterns can be related to specific injuries, and they can be changed, and the changes last… happy days!

It is important to remind ourselves that the movement changes achieved via gait retraining did not involve a runner setting off for a run and consciously trying to force a random modification to their form.

The subjects were on treadmills receiving external biofeedback that was gradually reduced over an 8-10 week period. The movement pattern involved had been carefully selected following strict biomechanical assessment and was for a specific injury. As Davis states:

“if you try to ‘fix’ your stride when you’re uninjured, it’s more likely that you’ll cause an injury than prevent one.”

Gradual removal of the external feedback over a period of time could well have aided the conversion of a conscious effort become an unconscious one. Whether the movement ever became totally automatic for the subjects is hard to tell, as is whether overall running efficiency was improved.

That said, with the injury symptoms gone and not returning, you would imagine overall gains must have been higher than being injured and unable to run. Dr. Davis concludes: “I believe abnormal running mechanics are a factor in most running injuries, and in most cases these flaws can be corrected, but at present very few of the professionals who treat injured runners suggest stride alterations.”

If you’re interested in learning more about how to improve your own running form and develop the most efficient stride for YOUR biomechanics, signup for our 6-week online form course. The online course will help you run with proper form by teaching you the science of running biomechanics and provide you with a simple-to-follow, progressive set of exercises, drills and mental cues to help you make lasting changes to your form.

I hope you have found this insight stimulating and as always look forward to feedback and comments.

Happy running!

Matt Phillips is a Running Injury Specialist & Video Gait Analyst at

StrideUK

& Studio57clinic. Follow Matt on Twitter: @sportinjurymatt

References

1. Davis, I.: Gait Retraining In Runners. (2005) http://www.udel.edu/PT/PT%20Clinical%20Services/journalclub/caserounds/07_08/Dec07/GaitRetrain_OP.pdf

2. Dingwell et al.: Use of an instrumented treadmill for real-time gait symmetry evaluation and feedback in normal and trans-tibial amputee subjects. (1996)

http://oandplibrary.net/poi/pdf/1996_02.pdf#page=41

3. White et al.: Altering Asymmetric Limb Loading After Hip Arthroplasty Using Real-Time Dynamic Feedback When Walking. (2005)

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0003999305003953

4. Fitzgerald, M.: Are You Committing These Form Flaws? 2012

http://running.competitor.com/2012/10/injury-prevention/are-you-committing-these-form-flaws_292

2 Responses

I hope this comment isn’t hopelessly far removed from the date of the post. I couldn’t tell. At any rate, this and other articles that are so helpful on your site do result in a persistent question that comes up for me:

Q: While I realize the necessary practical advantage of using a treadmill for filming, analysis, and bio-feedback corrective techniques, is there a difference in gait between treadmill running and natural ground running? For example, it seems like the belt could pull one’s foot back in a way that falsely aligns it more than it would when you’re just pushing off unmoving ground, in effect minimizing what really could be going on.

2nd question is the last sentence in Study #1 before Conclusions: “The analysis revealed that hip external rotation and abduction were still being maintained, but the knee was returning to pre-training state.” Does maintained mean they are doing the good, improved thing, and pre-training means the knee is going back in, in the previous “bad” way? If so, is the angle of knee not as crucial as strengthening those hip abductors? Thank you so much. I am learning a ton from your well-written articles, though of course for every 1 thing I learn, I have five new questions. 🙂

Hi Kendra! Many thanks for the comments and what are some very good questions.

Research suggests that the difference between running on a treadmill and running over ground is actually less than you would imagine. Probably the best thing I can do is direct you to this article that gives a wealth of information on the subject.

With regards to your second question, I cannot unfortunately see in detail the graphs on the original study that explain the knee frontal plane patterns after six months. I shall endeavour to contact Dr Davis to clarify this point for you. The most relevant outcome from the study is that abnormal mechanics were indeed causing the symptoms and that gait retraining lead to the runner being able to maintain these new patterns over a 6-month period.

The “five new questions from every 1 thing learnt” never ends. The more we learn the more we realise how little we know!