A topic that’s probably crossed every runner’s mind in the past year or two is footstrike style. With the rise of barefoot running and minimalist shoes, there’s an inevitable debate going on about the risks and benefits of the various types of footstrikes.

Instead of investigating the wide range of claims made by minimalist proponents or opponents, in this article we’ll just take a look at what we do know about footstrike styles and injuries from the scientific literature.

Defining the three types of footstrike

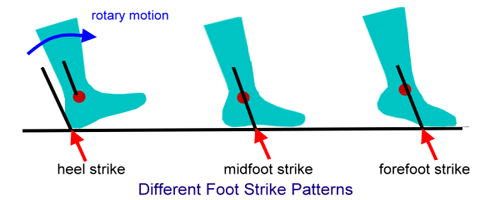

Broadly, there are three ways that your foot can hit the ground.

- In a heelstrike style (rearfoot), which is by far the most common (accounting for 75-90% of runners, depending on your source), your heel contacts the ground first followed by the rest of your foot, which pivots downward from your previously dorsiflexed ankle.

- In a midfoot strike, the ankle is more plantarflexed, and the outside edge of your whole foot contacts the ground first.

- Finally, in a forefoot strike, the outside edge of the forefoot contacts the ground first, with the ankle dorsiflexing to pivot the midfoot and heel down to the ground afterward.

The classic “advantage” cited for forefoot striking is a lower impact force when the foot hits the ground, probably because the ankle temporarily turns the vertical impact force at the forefoot into rotational force. Impact forces have been implicated in a few injuries, though certainly not all or even most.

Forefoot striking also appears to become more common the faster you go—almost all middle-distance runners forefoot strike in their races, for example, and every international sprinter lands on the forefoot while sprinting.

While the three footstrike styles are visually different, what are the differences on the biomechanical level?

Unfortunately, most of the research which answers this uses rearfoot strikers who have been instructed in forefoot striking, not natural forefoot strikers. However, these studies justify this by citing a 1998 study by Irene Davis and Dorsey Williams that demonstrated no statistical differences in “converted” forefoot strikers when compared to natural forefoot strikers.

Additionally, there is almost no research on midfoot striking, perhaps because of the difficulty of pinning down what exactly constitutes a “midfoot strike.”

Footstrike in focus

The first study we’ll examine is a 2004 paper by Carrie Laughton Stackhouse et al. The intent of the paper was to examine the effects of both footstrike pattern and orthotics on the motion of the foot while running; we’re only interested in the effects of footstrike. Using fifteen runners, Stackhouse et al. examined their foot and lower leg motion while running on a treadmill at 7:15 mile pace.

- A large difference was observed between forefoot striking and heelstriking when it came to ankle dorsiflexion—this makes sense, because there’s no way you can forefoot strike without having a plantarflexed ankle when you hit the ground!

- Forefoot striking also resulted in greater rearfoot eversion, meaning the runners pronated somewhat more when forefoot striking. But this difference was only mild, and none of what we’ve seen is directly correlated with injury, barring perhaps a weak relationship with pronation and a few injuries like shin splints, so we’ll have to look elsewhere for clues on how footstrike could affect injury rates.

In a later study conducted in 2007 by F.I. Kleindienst and coworkers in Germany, nineteen serious male runners averaging 35 miles a week were analyzed in a similar fashion as Stackhouse et al.

The runners were all rearfoot strikers and were measured first while in their natural strike pattern and later in a converted forefoot strike pattern. The results were largely in agreement with Stackhouse et al., but fortunately, Kleindienst and the other researchers took the additional step of calculating the work done by the forefoot, ankle, and knee joints.

Higher work done at a joint means more energy is being absorbed: Doing a calf raise off a step, for example, involves more work at the ankle joint than doing one on flat ground or while wearing shoes with an elevated heel.

- To this end, Kleindienst et al. found that the converted forefoot strike pattern increased the work at the forefoot and ankle, but decreased the work done at the knee.

- There were also differences noted in knee abduction and rotation—forefoot striking also seemed to increase abduction and internal rotation at the knee, which is a bad thing when it comes to injury. However, this is likely offset by the lower overall work being done at the knee joint.

- Additionally, while the classic impact peak was gone in the forefoot striking pattern (as we would expect), the overall forces hit a higher peak when the runners were striking with their forefoot first. This, plus some of the discrepancies in Stackhouse et al., makes me wonder whether a “converted” footstrike style is truly equal to one that occurs naturally or has been practiced for many months or years.

Impact and loading rate

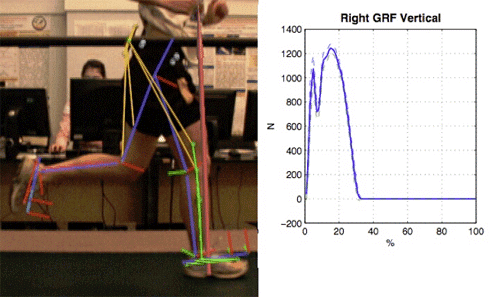

Most runners believe that landing on the forefoot or on the mid-foot automatically reduces impact loading rates compared to heel-striking. However, bio-mechanical analysis reveals that this assumption is false. Consider these two graphs of impact force conducted by Jay Dicharry

In this first image, you’ll notice the runner has a midfoot strike. As such, you would expect a small loading rate and only one impact peak. However, as you’ll notice, there are two impact peaks and the slope of the first impact is very steep (suggesting that the impact was quite forceful).

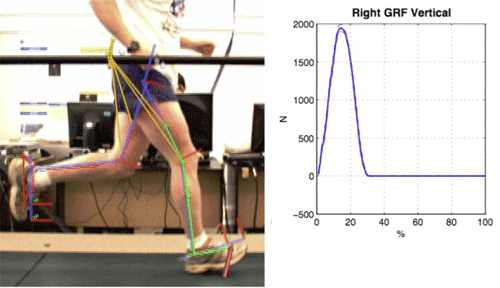

Now, let’s compare that midfoot strike to a classic heel striker. In this graph, you see that there is only one impact peak and the slope of the impact is much more gradual than the above mid-foot strike (suggesting the impact was less jarring).

Jay Dicharry suggests that this difference has to do not with footsrike, but rather with where the foot lands in conjunction with the body’s center of mass. Generally, heel striking occurs when you “reach out” with your leg and strike the ground in front of your center of mass. However, heel-striking doesn’t always occur in this fashion. Case in point: Meb Keflezighi, who is a heel striker (and a fast one), but whose foot lands under his center of mass.

In summary, footstrike itself is not the only factor that influences loading and impact rates. Perhaps more important is where the foot strikes the ground in relation to your center of mass.

Is footstrike a factor in running injuries?

When it comes to actual injury rates in forefoot and heelstrikers, there is relatively limited information.

A small study on college distance runners at Harvard University found a higher injury rate among heelstrikers, but Kleindienst cites two much larger studies (unfortunately published only in German) which found no difference in overall injury rates. One, however, did find a difference in types of injury.

No further evidence was provided on this front, but this would make sense given what we know about impact forces and the work done at the forefoot, ankle, and knee during forefoot and heel striking.

A forefoot strike would reduce the impact force and offload the knee, but at the expense of additional loading on the forefoot and ankle joints. A heelstrike would in turn offload the forefoot and ankle, but increase the impact force going up the heel and shin and also increase the work done by the knee joint. Kleindienst et al. agree, writing:

It is concluded, that the “conventional” dynamic variables does not lead necessarily to a lower risk of FFS [forefoot striking] regarding the development of running related injuries. It is likely that the location of the injuries/complaints can be influenced by the strike pattern. It has been suggested that altering the strike pattern may decrease the risk of developing certain injuries [and presumably increase the risk of developing others].

Should you work to change your footstrike?

Unless you’ve battled chronic injuries in your knee or shin for months or years, it probably makes sense to try less drastic things like increasing your stride frequency or doing some stretching and strengthening exercises before you consider altering your footstrike.

Podiatrists have begun to report seeing patients with foot injuries that develop after they switch to very minimal shoes or forefoot striking patterns, so keep in mind that changing how you run is not a risk-free decision.

Finally, do keep in mind that changing your foot strike pattern is a major endeavor. It will take a lot of practice to get it right, and as you change your foot strike pattern, you will be rapidly introducing brand-new stresses onto your body. So, while converting to a forefoot strike might help you take some strain off an aching knee, it will put a lot of stress onto your forefoot and ankle, which you likely are not prepared for.

In addition, changing one piece of your running form does not occur in isolation. Changing the position of your footstrike impacts your hip flexion, cadence, stride length and almost everything in the bio-mechanical chain. As such, you need to keep the entire body in mind if you plan to make changes to your form.

For example, when many runners hear they need to forefoot strike, they begin prancing on the balls of their feet without correcting their over-striding or properly extending their hips and driving from the hip and glute.

How to improve your form

If you’re interested in learning more about how to improve your own running form and develop the most efficient stride for YOUR biomechanics, signup for our 6-week online form course. The online course will help you run with proper form by teaching you the science of running biomechanics and provide you with a simple-to-follow, progressive set of exercises, drills and mental cues to help you make lasting changes to your form.

The course will be broken down into six modules so your body can adapt and respond to changes before moving on to the next step. We start with an overall conditioning program to ensure you have the strength and proprioceptive to make changes and then, starting from the arms and posture, break down every element of effective running form.

While we recognize there is no “perfect” way to run, we do believe that there are certain universal aspects of proper form that can be learned and improved to help almost every runner stay healthy and run more efficiently.

Right now the jury’s still out on whether there is an “ideal” type of footstrike. There is much more research to be done, especially when it comes to forefoot striking in habitual forefoot strikers, but for now, there’s no solid evidence that any particular footstrike is best for everyone. It may well be that footstrike is like pronation—a naturally-variable component of your stride which simply influences the timing and location of the forces absorbed by your body when you run.

3 Responses

Thanks for this Jeff!

I wonder why the graphs are the opposite of Lieberman’s:

http://barefootrunning.fas.harvard.edu/2FootStrikes&RunningShoes.html

Also curious why the second graph (heel strike) shows a load up to 2000, where the forefoot strike graph only hits 1200. Should I conclude that forefoot striking reduces loading rates?

Hi Brian, thanks for the comment!

The link you sent is a comparison between heel striking in shoes and heel striking without shoes. Not sure that relates to the points in this article. Did you mean to send a different link?

As to the two graphs, you’re right, overall load/impact is higher in heel striking, but the curve of the line is slightly more gradual, perhaps suggesting while heel striking demonstrates a higher overall load, it’s less jarring. Keep in mind also that a higher loading rate doesn’t necessarily mean higher injury rate.

This is all to say that we don’t have all the answers yet. There is still a lot we don’t know about how footstrike relates to injury risk.

Oops! I sent the wrong page. Here we go:

http://barefootrunning.fas.harvard.edu/4BiomechanicsofFootStrike.html

The graphs in the video thumbnails compare heel striking to forefoot striking both in shoes and barefoot. The heel strike has a transient but the forefoot strike doesn’t.

But yeah, who knows how that translates to injury risk!