In the last two weeks, we’ve talked a lot about core strength for runners: hips, abs, and back muscles. But there’s one more aspect of “core strength” that we haven’t talked about yet, and emerging research indicates it may play a big role in overall body stability. That aspect is a little-known muscle called the transverse abdominis.

What is the transverse abdominis

The transverse abdominis, or TVA for short, is a thin cylindrical muscle that lies underneath the abdominals. Its main role in daily life is to hold in the chest cavity (lest your innards sag outwards).

However, the TVA also plays an important role in running as well:

Contraction of the TVA compresses the chest cavity and increases its inner pressure, much like squeezing a deflated beach ball causes it to become stiff again. It’s postulated that this increase in pressure facilitates stability throughout the body, essentially “hardening” the connection between the upper and lower body.

So, how does this hardening help you improve your running, and does it have any relevance to injury prevention? As usual, we have to turn to the research.

The science of the transverse abdominis for runners

Transverse abdominis and lower back injuries

Early work on the TVA’s function in “dynamic” activities was done by Paul Hodges and Carolyn Richardson at the University of Queensland in Australia.1 Building on studies which suggested that the transverse abdominis played a role in stabilizing the spinal column, Hodges and Richardson recruited 15 subjects with chronic lower back pain and 15 healthy controls. Using electrodes to measure muscle activity in the transverse abdominis and other trunk muscles, the researchers asked the subjects to rapidly move their arms in a variety of directions while relaxing the rest of their body.

Their findings revealed that in all healthy subjects, the TVA contracted a few fractions of a second before the shoulder muscles fired. But in the subjects with chronic lower back pain, the TVA fired markedly after the shoulder muscles. Therefore, the researchers demonstrated a clear connection between stabilization and lower back injuries and the strength of the transverse abdominis muscle.

However, these subjects were “regular” everyday people, not runners. So, the question remains – do these same patterns show up in injured athletes, and do they affect lower limb movement as well?

Transverse abdominis and lower leg injuries

Sallie Cowan and her colleagues at the University of Melbourne investigated this same phenomenon in soccer players with chronic groin pain.2 Using a similar protocol, except swapping a leg-lifting test for the arm-lifting test, Cowan et al. found surprisingly similar results: in healthy subjects, the transverse abdominis activates before the “prime movers” for a particular joint, seemingly bracing the body before the movement is initiated, but in the chronically injured subjects, the transverse abdominis activates after the main muscles.

Simply speaking, a strong and healthy transverse abdominis helps the muscles prepare for movement and brace for impact by stabilizing the muscles, which results in a significant decrease in injury risk.

Is the transverse abdominis really at fault for many running injuries?

Many researchers and therapists interpret this previous research as evidence that the dysfunction of the TVA is one of the main causes of injury. Unfortunately, there have been relatively few follow-up studies, probably due to the difficulty of measurements: since the transverse abdominis is buried under two layers of muscle, you can’t measure its electrical activity unless you poke a needle or wire through the main abdominals.

However, a clinical study by Gregory Hicks et al. demonstrated that about 72% of people with chronic low back pain (remember, regular ordinary people, not athletes) will get at least some benefit from “abdominal bracing” exercises, with 33% completely recovering in eight weeks.3

This is encouraging, and gives some good circumstantial evidence to suspect that TVA activation and strengthening exercises will benefit runners with (or wishing to prevent) hip, lower back, and groin issues.

Still missing, however, are the powerful clinical studies showing a direct link between muscular dysfunction and injury. Until we’ve got those studies, the relationship between the transverse abdominis and injury remains tenuous.

But this evidence is still strong enough for Irene Davis, a well-respected researcher whose work has cropped up in the last few posts, to author a review which touched on the issue as it affects athletes and some practical exercises to strengthen the area.

Taking action – how you can improve your transverse abdominis

In Davis’ review, she recommends that patients begin with simple “stomach hollowing” exercises designed to isolate the TVA, then progress to more general exercises like Hicks’ “bracing.”

Stomach hollowing exercises

What is “stomach hollowing”? It’s an isolated contraction of the TVA that ‘sucks’ the stomach inward towards the spine, as you would do if you were trying to button a tight pair of pants.

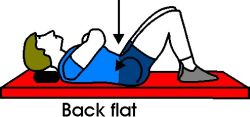

Hicks et al. suggest doing abdominal the following abdominal hollowing exercise: 30 x six-second “holds” of the stomach-hollowed position, as seen here:

If you find it difficult to isolate your TVA when performing this exercise, it wouldn’t be a bad idea to work on this once a day.

Stomach bracing exercises

If you do find it easy to isolate your TVA in the above exercise, then you can probably move on to “bracing” exercises like Hicks recommends. His paper had its subjects do 30 six-second “holds” of bracing the stomach (as if you were going to take a punch to the gut), with a few different varieties (with leg lifts, while doing a glute bridge, etc.) every day. Here are some examples of stomach bracing exercises:

I suspect you, being an athlete, could move fairly quickly from these into more traditional stability exercises like front, side, and back planks—note that, while these also strengthen the “traditional” abdominal muscles, they differ from crunches and sit-ups in that they are isometric: the body does not move while doing them. This is important, as the TVA seems to function exclusively as an isometric supporter, so (as Richardson points out in her paper), they are not strengthened by “dynamic” exercises like sit-ups.

Fortunately, that’s the final word on core strength (barring an earth-shaking new study, which isn’t out of the question!). Next week we’ll be moving to greener pastures. Until then, check to see whether or not it’s easy for you to isolate your TVA muscle, especially if you’ve had low back or groin issues.

One Response

Great read..Thank u!