Red light therapy is something I had been hearing about for quite some time, but honestly I was little skeptical that it was just the latest marketing fad.

But during the Paris Olympics last year and the build-up to the Tokyo World Championships last summer, I kept reading about more and more athletes who swore by it.

This put it on my “to research more” list, but it wasn’t until late this summer when my nagging plantar started to bother me again that I decided to finally dig deeper into the research and also try it out on myself.

So, in this article we’re going to dive deep into over 30 research studies to look at…

- What red light therapy is (without the technical jargon)

- What it does and how it works

- Explore the different types of red light therapy and which is best for runners

- Thoroughly examine the research to see if it has any merit and what it might be best used for

- And how to apply to your own training, recovery and injuries

What is red light therapy?

Red light therapy, which may also be called low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is essentially using specific wavelengths of light to trigger biological responses in your cells.

That probably sounds a bit sci-fi, but the mechanism is surprisingly straightforward once you understand what’s happening beneath your skin.

How does it work

Your cells contain tiny energy-producing factories called mitochondria (think of them as little power plants).

These mitochondria have a specific enzyme called cytochrome C oxidase that responds to certain wavelengths of red and near-infrared light, typically between 600 and 900 nanometers.

When light in this range penetrates your skin and reaches your cells, it activates this enzyme, which kicks the mitochondria into higher gear and causes them to increase ATP production.

ATP is basically the energy your cells use to perform all their critical functions.

And when your cells have more energy available, they can perform their normal functions more efficiently.

Why “Red Light” and Not Blue or Green

Red light therapy is often used interchangeably or as the default name for all laser therapy techniques.

But, red light therapy is actually a form of photobiomodulation, which is the scientific term for laser therapy.

This is important because it highlights why athletes use red light and not the blue or green wavelengths.

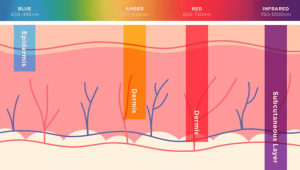

Green light therapy targets the cells on the surface of the skin and has been shown to help with skin blemishes like dark spots and sun spots.

Blue light penetrates a little deeper and is thus helpful for improving oily skin or reducing acne.

Red and near-infrared light, on the other hand, can penetrate several centimeters into your body – deep enough to reach injured Achilles tendons, strained calf muscles, or inflamed plantar fascia.

Does the Research Suggest It Even Works?

This all sound good in theory, but can red light therapy actually make a difference with our running and recovery?

Luckily, exercise scientists have been working on this for quite some time and we have quite a few research studies to glean data from.

Speeding up Recovery

Increasing ATP production in the mitochondria should give the cells more energy to aid in the overall recovery process post-workout.

Perhaps the most convincing study came in 2024 from Li and colleagues, who examined multiple physical therapy modalities and their impact on recovery.

The results that photobiomodulation demonstrated a significant advantage over placebo at reducing muscle soreness 24 hours post-workout, with a standardized mean difference of -3.91.

For all you science-nerds, that’s a pretty big difference.

This study also showed that the majority of the recovery gains occurred within 48 hours of completing the workout, which means it’s best to use red light therapy directly after hard sessions.

Unfortunately, most runners I work with only think about recovery tools after they’re already suffering.

But red light therapy is one of the few modalities I have seen that shows promise of reducing post-workout soreness and enhancing recovery when used before a workout.

In fact, a 2025 meta analysis found that use of red light laser therapy before exercising decreased soreness from 24 to 96 hours post-exercise and reduced creatine kinase levels (a marker of muscle damage) for up to 96 hours afterward.

That’s pretty compelling if you’re trying to string together quality workouts with minimal recovery time between them.

After seeing this research, I was particularly interested in the mechanisms for why red light therapy could be so helpful in reducing soreness and boosting recovery.

The clearest explanation comes from Dr. Michael Hamblin’s work at Harvard Medical School.

Hamblin’s research showed that PBM (red light therapy) works by up-regulating your body’s natural antioxidant defenses and reduces oxidative stress.

This leads to an overall reduction in inflammation, particularly in joint disorders and traumatic injuries and can activate healing pathways in normal cells and already-inflamed tissue.

Another interesting find from research conduced by Dr. Cleber Ferraresi’s found that PBM can increase muscle strength gains, speed up adaptation to training, and extend time to exhaustion during exercise—all while reducing blood lactate, muscle fatigue, and injury markers.

I took this to signify that training at the same intensities becomes easier and thus incurs less fatigue and requires less recovery.

Healing Injuries

The most common application for red light therapy seems to be in the form of speeding up healing from common overuse injuries.

Plantar Fasciitis

If you’re dealing with plantar fasciitis, there’s genuine reason for optimism.

- A 2024 randomized controlled trial by Ketz and colleagues found that photobiomodulation plus usual care was significantly better than usual care alone.

- A 2023 systematic review by Ferlito concluded that PBMT effectively reduces pain intensity and disability in plantar fasciitis compared to control conditions.

- Even better, a meta-analysis examining seven trials found that PBM not only reduces pain but also improves foot function and reduces the thickness of the plantar fascia itself.

For runners battling plantar fasciitis while trying to maintain training, PBM appears to be one of the more evidence-based adjunct therapies available.

Achilles Issues

Given how common Achilles problems are among distance runners, this is often where runners first encounter PBM.

Unfortunately, the evidence here is considerably weaker.

A 2022 systematic review and meta-analysis by Rocha and colleagues specifically examining Achilles tendon pain found no significant acute or chronic effects of photobiomodulation compared to control groups.

My take on this evidence is that since the Achilles is the largest and strongest tendon in the body, red light therapy can’t effectively penetrate the area to provide the intended healing effect.

Runner’s Knee

Research on patellar tendinopathy specifically in runners is limited, but studies on athletes engaged in jumping sports provide relevant insights.

A study by Morimoto and colleagues on 41 patients (including various sports injuries) found red light therapy particularly effective for runner’s knee, with a 65.9% effectiveness rate using pain relief scores.

Research also indicates that red light therapy has been shown to improve pain and function in chronic patellar tendinopathy.

For example, randomized controlled studies demonstrate that athletes receiving low-level laser therapy plus eccentric exercise (decline squats) showed greater improvements in knee pain and functional scores than either exercise alone or laser alone.

What to look for if you want to try

After seeing the evidence, I was convinced I wanted to give red light therapy a try, especially for my nagging plantar but also because I’m always looking for ways to recover faster.

But, like is almost always the case with emerging technology, shifting through a lot of the marketing hype to find the best device isn’t easy.

Since it’s not regulated, “red light therapy” can mean anything from a $50 LED panel on Amazon to a $3,000 professional-grade unit.

There’s no standard for what counts as “red light therapy” since the wavelengths might be right, wrong, or not disclosed at all or the device might have been tested for efficacy or just designed to glow red.

Luckily, reviewing the literature gives some really good guidelines to follow. Specifically, if you’re using red light therapy for running then you want a device that…

- Uses a wavelength between 600-900nm (and it should be clearly stated)

- Has near-infrared capability (800nm+) for deeper tissue injuries

- And has the ability to position the light close to the target tissue or injury

After sifting through the options and different budget options, I found PRUNGO.

Unlike a lot of devices, it is really easy to target specific areas on the body, which is what most interested me. Most of the other options I came across where designed more for skin wellness or were far too bulky or expensive.

Plus, I liked their focus on the science and innovation of the technology.

Specifically how they use a more focused, polarized laser for deeper penetration.

When looking at the research, especially for specific injury healing, an 850nm wavelength shows a lot of promise to be more effective since it can penetrate deeper.

I’ve been using it on my plantar and I noticed a big difference in the first few days.

I was lucky that it wasn’t bothering me during runs, mostly when I’d walk or stand for long periods of time or if I was barefoot a lot (which happened more often in the summer).

But, having had plantar fasciitis before, I knew this was an early warning sign.

Thankfully, the last few weeks I haven’t noticed my plantar at all.

I still need to be cautious, but it’s definitely a mental relief to know that I may have dodged a bullet.

I am excited to try out the red light therapy on my calves and quads before running once I get this plantar settled for good.

Final Thoughts: Can you benefit?

If you’re considering red light therapy, here’s my coaching advice:

Do your homework first.

Don’t invest in expensive devices or treatments without understanding the specific protocol required for your goal.

A random 5-minute session with an unknown device is unlikely to match the parameters used in successful research studies.

Timing matters more than you think.

The research consistently shows that pre-exercise application works better than post-exercise for most outcomes.

If you’re targeting increased recovery or performance enhancement, use PBM before your hard workout, not after.

It’s not a replacement for smart training.

PBM might give you a 3-5% edge in recovery or running economy, but poor training progression, inadequate sleep, or nutritional deficiencies will overwhelm any marginal gains from light therapy.

For overuse injuries, context is everything.

If you have plantar fasciitis, runner’s knee or other more superficial overuse injuries than the evidence supports adding PBM to your treatment plan.

If you have Achilles tendinopathy or deeper hamstring injuries, focus on evidence-based rehab protocols (eccentric loading) and consider PBM as a modest adjunct at best.

That’s not to say PBM won’t help overall recovery, just don’t expect miracles or for it to be your only modality.

The research on red light therapy for runners is evolving rapidly, but I think we can say we’re beyond the “does it work?” question.

The answer is clearly “yes, for some outcomes, under specific conditions.”

Now we’re refining the “when, how, and for whom” questions.

As with most interventions in sports science, the devil is in the details, and individual experimentation within evidence-based parameters is often necessary.