If you are a female runner who ever suffered from knee pain, chances are you have come across an idea. That female runners are more susceptible to knee pain than their male counterparts. Why? Because they have wider hips.

You may have been introduced to the term Q Angle. And been told that because your angle is greater, your knees are put under more strain. You may have been told that your knees are out of alignment (pointing the wrong way). Or ‘maltracking’ (moving in the wrong direction).

There is no doubt that men and women do tend to have anatomical differences in the structure of their hips and legs. And it makes sense that these differences may cause subtle contrasts in running form. But the question is do these anatomical differences actually cause knee pain?

Are women with wide hips (or men for that matter) prone to join the many runners who suffer from knee pain every year? Should female runners be performing special ‘corrective’ exercises targeted at restoring ‘normal’ knee position and or movement?

Let’s take a look at what the evidence says.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

The type of knee pain we are looking at in this article is what the medical profession refers to as Patellofemoral Pain syndrome (PFPS). Most runners know it by its more familiar name ‘Runner’s Knee.’ Characterized by pain around the edges of and under the kneecap.

As one of the most common types of running related knee injury, the research shows that female runners tend to suffer from PFPS more than male runners.

Types of treatment can vary considerably depending on who you visit. Especially for female runners who very often find themselves going through gender specific screening and rehabilitation.

It is important at this point to differentiate PFPS from ITB Syndrome. Whereas with PFPS you’ll experience pain on the edges or underneath the actual knee cap. ITB syndrome involves pain more towards the outside of the knee joint, away from the actual knee cap.

The causes and solutions differ. So it is important to see a professional and get a clear diagnosis. For more on ITB, please read Treating IT Band Syndrome.

How Big is Your Q Angle?

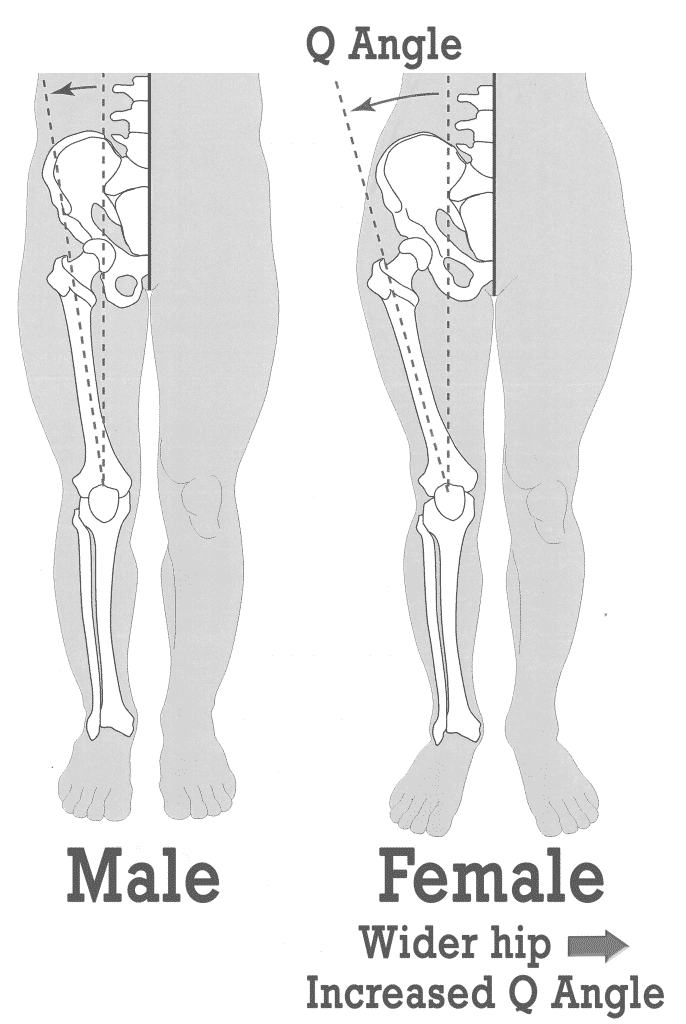

When it comes to PFPS you will often hear talk of the Q angle. As shown in the diagram below. This angle is measured by taking a line from the top edge of the hips (a bony prominence called the anterior superior iliac spine) and connecting it to the centre of the kneecap.

The angle between this line and a vertical line is called the Q angle. With ‘Q’ standing for Quadriceps (the muscles on the front of the thigh). The wider the hips, the greater the Q angle will be, with the thighs effectively angling in more steeply towards the knees.

So, why is the Q angle significant? The commonly held conception is as follows: a greater Q angle will put more strain on the knees. Because the quadriceps muscles end up pulling the knee cap (patella) away from its natural ‘groove.’

This patella maltracking is thought to cause friction against structures under the knee. Resulting in symptomatic pain around the edges of and under the knee cap. In an attempt to be more specific than PFPS, a diagnosis sometimes given is Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome (PFTS).

And the solution typically focuses on restoring ‘natural tracking’ of the knee cap in its groove by strengthening and stretching stretching where necessary.

Patella Maltracking: Limitations

Despite the popularity of this type of ‘corrective’ treatment and the complete sense it makes to both runners and therapists, the assumption that a ‘maltracking knee’ causes pain is far from watertight.

The problem centers in the commonly held belief that as humans we are all built and move in the same way. With this way of thinking, we conclude that any movement ‘away from the norm’ will ultimately cause pain. Unfortunately, one can challenge such reasoning. How do we explain runners with ‘maltracking knees’ who are not in pain? And how about runners with ‘normal tracking’ but are suffering from knee pain?

In a study entitled ‘Patellofemoral joint kinematics in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome’ (MacIntyre et al. 2006), patellae (knee caps) movement of 60 volunteers was recorded using a magnetic resonance imaging-based method, at five different angles of flexion (-40 to 600). The 60 volunteers split into three distinct groups:

- Group 1: 20 subjects with patellofemoral pain and clinical ‘evidence’ of malalignment.

- Group 2: 20 subjects with patellofemoral pain but no signs of malalignment.

- Group 3: 20 subjects with no knee issues.

Results From The Study

- No differences in the overall pattern of patellar motion.

- Varying patterns of patellar spin (rotating in or out) and tilt (inwards/outwards) across all three groups with nothing specific to any one group.

- At 190 of knee flexion the patellae of Group 1 (patellofemoral pain & malalignment) were positioned an average of 2.25 mm more laterally (towards the outer side) than the patellae in the control group.

- Although point 3 suggests correlation between a laterally placed knee and patellofemoral pain, it is highly doubtful that any therapist is going to be able to spot a 2.25mm displacement using their eyes. In effect, the study concludes “it is clear from the data that an individual with patellofemoral pain syndrome can not be distinguished from a control subject by examining patterns of spin, tilt, or lateral translation of the patella.”

The Vastus Medialis Obliquus

Putting the conclusion of this study to one side for the moment, we need to now mention the Vastus Medialis Obliquus, VM or VMO for short. This muscle lies on the inside of the thigh. Female runners suffering from PFPS are very often given strengthening exercises. In an attempt to end their pain.

After all, it makes sense doesn’t it? If your knee is being pulled to the outside because of your wide hips and excessive Q angle, strengthening the muscles on the inside of the thigh will help pull it back, right?

Unfortunately, once again, despite the attractiveness and apparent logic of such a solution, the research does not support such assumptions. Dissection studies negate any link between patellofemoral pain with size, length or angle of the VM.

It’s a sobering thought but the evidence suggests that any efforts to ‘correct a maltracking knee’ be it strengthening the VM, stretching the ITB, wearing a knee brace, even surgery, could well be a waste of time and money.

So Why Do Female Runners Suffer More Knee Pain?

So, if PFPS in female runners is not a product of wide hips, a larger Q angle, maltracking knees or weak VMs, why is it that female runners seem to suffer it more than male runners? The only answer I have for you is we don’t know yet.

Maybe there is some biological reason we haven’t discovered yet. There is some fantastic research currently happening into gender specific running injury screening. And prevention but as of yet the results are far from conclusive.

Until we have more information, the take home message is watch out for spending too much time and money on ‘fixing’ bio-mechanical ‘flaws.’ This can be very tricky for the modern female runner as there is a huge industry out there currently training therapists up to become ‘biomechanics experts.’

There are a whole bunch of therapists out there itching to take you down a road of ‘corrective’ therapy to try and get your knees looking ‘normal’, despite what the evidence says.

This isn’t to say that biomechanics is not important. It obviously is but when it comes to running related injury. All the evidence to date points towards checking the basics first rather than getting blinded by structural ‘issues’ like patella maltracking, leg length differences, high arches, low arches, overpronation, anterior tilted pelvis, etc.

Especially when there isn’t a lot of evidence that these structural ‘issues’ are actually issues at all. By ‘checking the basics’ I am referring to understanding and putting into practice what we do know about pain, injury and thresholds.

To learn more about gender specific injuries, please read Are Women More Prone To Running Injuries.

Pain, Injury and Thresholds

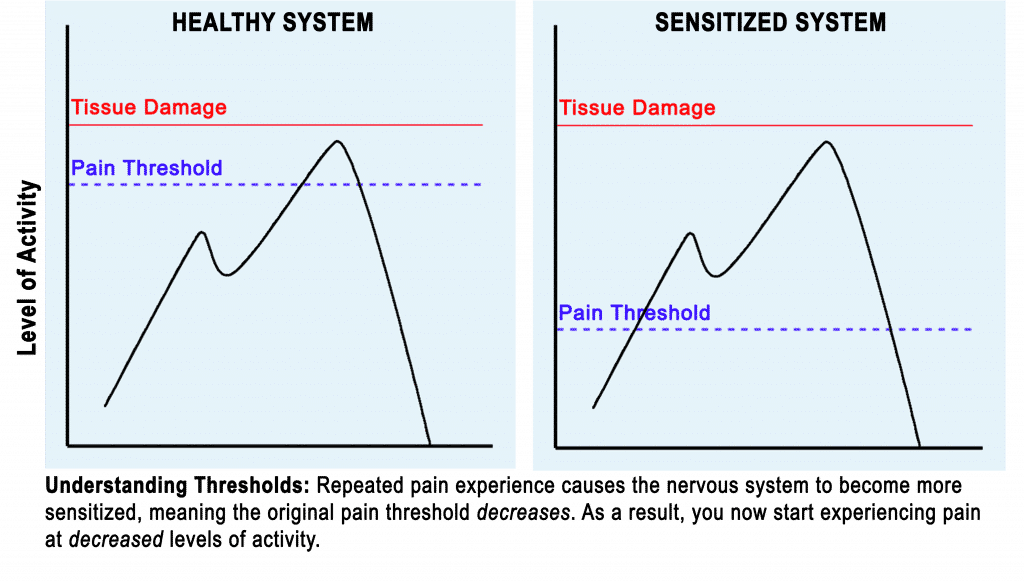

Every tissue in your body has a threshold. A maximum load it can take before damage results. Asking them to do more than they are capable of produces pain.

Our bodies have a very clever way of warning us if we are getting too close to our ‘tissue damage’ threshold. In a word, pain. In the diagram, you see that slightly underneath the tissue damage threshold lies a ‘pain threshold.’ At this level of activity, the nervous system outputs pain. With the idea that we will immediately modify what we are doing.

For example pulling our hand away from a boiling hot pan. It’s a fantastic system and helps us realize that pain is our ally. A system of defence, and certainly not the enemy.

For further protection following either a near miss or actual tissue damage, our nervous system reduces the pain threshold. Alarm bells now ring at slightly lower levels of activity than before. Reducing our capacity in this way ensures that we give our body time to heal.

However, if we ignore the pain warnings, the nervous system will react by reducing the pain threshold for that tissue even more. And will continue doing so until we essentially start listening. In other words, our system becomes overly sensitized. And it takes increasingly less activity for us to start feeling pain.

Let’s Look At An Example

So let’s put this into an example of patellofemoral pain. Imagine you run too much one week, too fast or too many days in a row. During one of your runs, your knee starts hurting at mile 6. You are crossing a pain threshold. You ignore the pain (or maybe don’t even notice it) and the tissue damage threshold is crossed.

Your body goes into protective mode. The more serious the damage or threat the more protective your system gets. Pain thresholds reduce and the next day you only manage to run 4 miles when pain starts. A few days later you only manage 2 miles.

Today you can’t even walk without it hurting. These are clear examples of a decreasing pain threshold due to too much activity.

Until you stop provoking your system into protecting itself, it will continue to decrease pain thresholds. It may even start sending pain out to new areas, even to the other knee. The problem with knees is they are used so much in everyday activity.

Rather like the ITB band, the Achilles tendon or plantar fascia. It’s no coincidence that these areas of the body can be very tricky to rehab properly. It’s way too easy to exceed thresholds and inhibit recovery. With regards to knee pain, everyday activities that you may not realise increase system threat include:

- Getting into, out of or holding a squat position, e.g. at work, gardening, etc.

- Keeping the knees in one position, e.g. at a desk, on the train, in a car.

- Going up and down stairs

- Walking too far or too often.

Rest May Not Be The Answer

In the early stages of PFPS or when the pain is very high, resting the tissues and desensitizing the system is crucial. However, once the system has calmed down you will now need to start gradually building it back up.

Many runners discover the hard way that total rest does not always allow a return to running. Pain thresholds will not automatically return to their prior levels. This is where rehab comes into play. Progressive loading of the tissues to gently push the thresholds back up.

What you do and how much you do is important as if you do too much those thresholds could easily come back down again. This is where a skilled therapist can really help you by setting a suitably graded loading program and monitoring your recovery over a few weeks.

This is where 9 times out of 10 you need to patiently devote your time and effort in order to reach full recovery.

Conclusion

Data does suggest that female runners suffer from knee pain more than men. The commonly held assumption that this is due to having wider hips has flaws though. The fact that not all female runners suffer from knee pain itself challenges such an idea. Furthermore, the mechanism used to explain why wider hips causes knee pain has no supporting evidence.

There are plenty of female runners out there with maltracking knees who are not in pain. Just as there are plenty of female runners with ‘normal tracking knees’ who are in pain. The persistence of blaming pain on ‘abnormal structure’ or ‘misalignment’ is an age old issue in the world of therapy provision.

And it is only recently that concepts from modern pain science have started to challenge traditional misconceptions of what pain is and how it works. Please read Good Hurt Versus Pain for more on this subject.

If you are a female runner suffering from patellofemoral pain, be vigilant of blaming (or letting anyone else blame) your anatomical shape. Take time to understand and appreciate the concepts of pain and tissue thresholds. And with the help of an equally appreciative therapist guide yourself through a suitably progressive loading program.